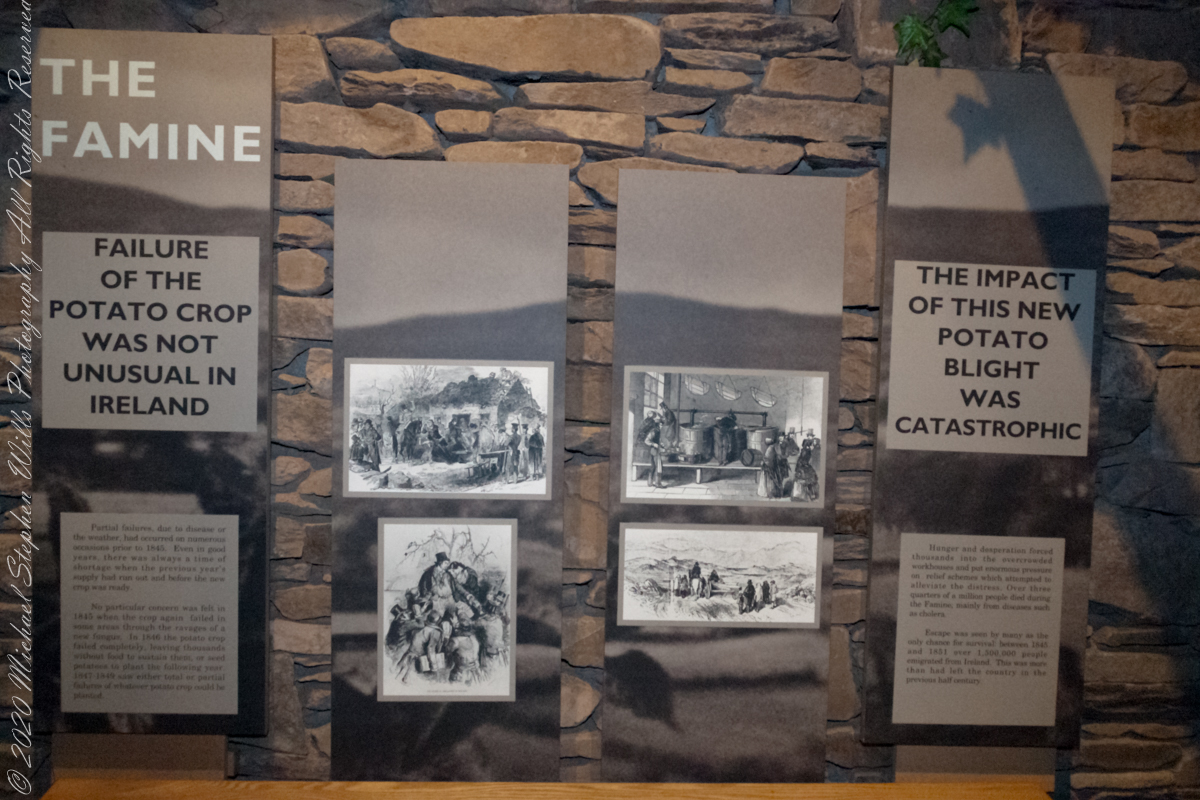

“Partial failures, due to disease or the weather, had occurred on numerous occasions prior to 1845. Even in good years, there was always a time of shortage when the previous year’s supply had run out and before the new crop was ready.”

“No particular concern was felt in 1845 when the crop again failed in some areas through the ravages of a new fungus. In 1846 the potato crop failed completely, leaving thousands without food to sustain them, or seed potatoes to plant the following year. 1847 – 1849 saw either total or partial failures of whatever potato crop could be planted.”

“Hunger and desperation forced thousands into the overcrowded workhouses and put enormous pressure on relief schemes which attempted to alleviate the distress. Over three quarters of a million people died during the Famine, mainly from diseases such as cholera. Escape was seen by many as the only change for survival: between 1845 and 1851 over 1.5 million people emigrated from Ireland. This was more than had left the country in the previous half century.”

The Great Famine of Ireland, often referred to as the “Irish Potato Famine,” occurred between 1845 and 1852, with the most acute suffering taking place between 1847 and 1849. The causes of this devastating period in Irish history are multifaceted and debated among historians, but the following are generally acknowledged as the primary factors:

Potato Blight (Phytophthora infestans): The immediate cause of the famine was a potato disease known as late blight. The potato was a staple crop in Ireland, and for many poor Irish, it was the primary source of nutrition. The blight destroyed the potato crop year after year, leading to widespread hunger.

Over-reliance on a Single Variety of Potato: The Irish mainly grew a type of potato called the “Lumper,” which was particularly susceptible to the blight. This lack of genetic diversity made the entire crop more vulnerable to disease.

Land Ownership and Tenancy: Most of the land in Ireland was owned by a small number of landlords, many of whom were absentee, living in England. The Irish Catholic majority often worked as tenant farmers, living on small plots of land and paying rent to these landlords. The land was subdivided among heirs, leading to plots becoming increasingly smaller and less productive over generations.

British Colonial Policies: The relationship between Ireland and Britain played a significant role in exacerbating the famine’s effects. Some British policies and economic theories at the time discouraged intervention. For instance:

Corn Laws: These tariffs protected British grain producers from cheaper foreign competition, making grain more expensive and less accessible for the starving Irish.

Economic Beliefs: The prevailing laissez-faire economic philosophy of the time held that markets should be allowed to self-regulate without government intervention.

Exports: Even as the famine raged, Ireland continued to export food (like grain, meat, and dairy) to Britain, which was a source of controversy. Many felt these exports should have been halted or reduced to feed the starving Irish population.

Inadequate Relief Efforts: While the British government did undertake some relief measures, such as opening public works projects and distributing maize (known as “peel’s brimstone”), these efforts were often insufficient, mismanaged, or too late. The public works projects sometimes did not lead to meaningful infrastructure improvements and instead focused on tasks like building roads that led nowhere.

Social and Cultural Factors: Discrimination against the Irish Catholics by the Protestant English elite, language barriers (many Irish spoke only Gaelic), and distrust between the local population and English officials further complicated relief efforts.

The Great Famine had profound social, cultural, and political impacts on Ireland and its relationship with Britain. It led to a significant decline in the Irish population due to death and mass emigration and is remembered as one of the darkest periods in Irish history. The event also left deep scars on the collective memory of the Irish people and played a role in the growth of Irish nationalism and the push for Irish independence in the following decades.

Reference: text in quotes is from “The Famine” poster. Cobh Heritage Center, May 2014.

Copyright 2023 Michael Stephen Wills All Rights Reserved

The Great Famine. When so many of my mother’s ancestors and my Mr’s, people came to Dundee. An absolute holocaust of its day.

LikeLiked by 2 people

See The Great Shame: And the Triumph of the Irish in the English-Speaking World

by Thomas Keneally

LikeLike

Michael, a truly horrific figure of deaths … with only that possibility on the horizon no wonder so many had to emigrate.

LikeLiked by 1 person

See “The Great Shame: And the Triumph of the Irish in the English-Speaking World” by Thomas Keneally

LikeLiked by 1 person

I will and have just found a second hand copy for sale. Thought I recognised the name – Thomas Keneally of Schindler’s List fame! Reckon this book might be slightly similar vein as Swedish writer Vilhelm Moeberg’s novel ‘The Emigrants’ based on a family part of the quarter million Swedes who left their country owing to starvation and death.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Keneally is the same author, in the forward he attributes the urge to write “Shame” from his work on “List”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very sad.

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLiked by 2 people

Good Morning, Theresa. See The Great Shame: And the Triumph of the Irish in the English-Speaking World

by Thomas Keneally

LikeLike

My Mother was Irish and she gave a book called “The Potato Famine” to my Father. He was shocked and upset by it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

See “The Great Shame: And the Triumph of the Irish in the English-Speaking World” by Thomas Keneally

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ok. Thanks for the reference.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure, Anne. More to come

LikeLiked by 1 person