The esker rises like a glacier’s spine, a long-backed remnant left behind where an ice mountain learned how to leave quietly. It is not loud geology—no cliffs shouting their age, no cataracts announcing force—but a patient, sinuous fact. A frozen river’s footprint, pressed into the land and then abandoned, it lies there still, grading itself gently on both sides, as if unwilling to offend gravity or time.

At first glance, it could pass for a human thing: a railroad berm, a raised roadbed, an engineer’s solution. Yet this ice-scribe ridge was shaped without blueprints, drafted by meltwater racing beneath a retreating glacier, carrying gravel like a hoard of stories. The stones settled where the ice allowed them, stacked by pressure and patience, forming a ridge long enough—nine-tenths of a mile—to tell a stream where it must turn.

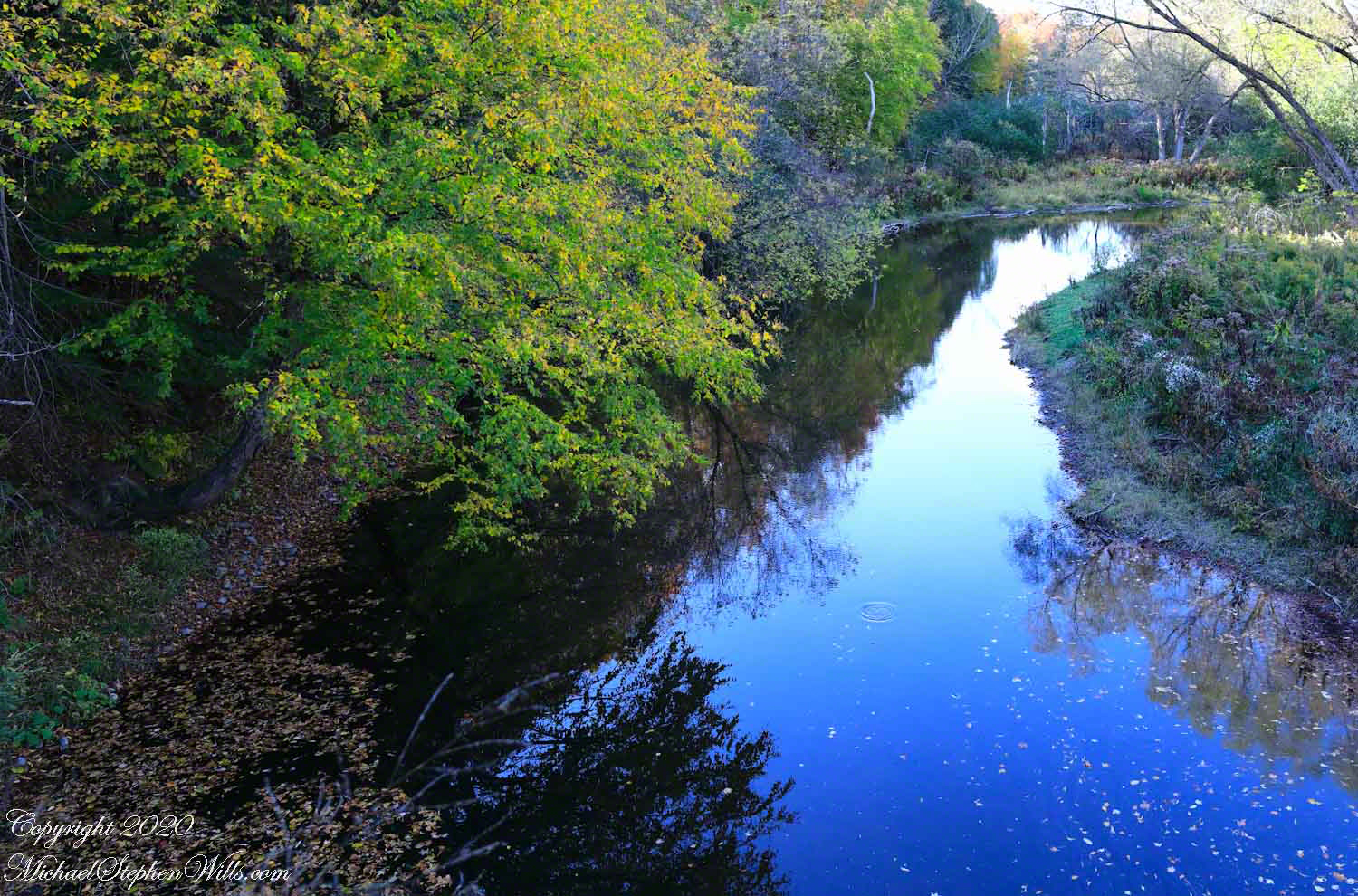

Fall Creek arrives with purpose, confident in its descent, until it meets the esker and must reconsider. Here the water performs bows, an abrupt acknowledgment of authority. The creek becomes a liquid negotiator, redirected by the ridge’s quiet insistence. This is the esker’s work: not domination, but persuasion. Land teaching water a new sentence.

Standing at the foot of the esker, the slope to the right reveals itself slowly. It does not announce, I am important. Instead, it waits to be noticed. A swamp settles nearby, the water-mirror lowland, collecting what seeps and lingers. Together, ridge and wetland form a conversation: height and hollow, drain and gather, spine and lung.

Before there was signage, before placards translated glacial grammar into public language, the land already knew itself. Knowledge preceded explanation. My son and I pitched a tent atop a kame at our front door — another ice-left hill, a deposit of ancient momentum. That night, the ground beneath us was older than memory and younger than myth. Camping there was not recreation so much as apprenticeship.

A kame is a meltwater’s knuckle, rounded and abrupt, shaped by collapse rather than flow. To sleep upon it is to rest on uncertainty made solid. The tent fabric whispered in the breeze, a thin membrane between human breath and glacial aftermath. Fireflies stitched brief constellations above the grass, while the earth held fast, remembering ice that no longer needed remembering.

Walking along Fall Creek later, watching it turn west where the kame insists upon geometry, one begins to sense the land’s authorship. This is not random scenery. It is edited terrain. Each ridge, each bend, each saturated hollow is a sentence left behind by ice that once covered everything and then, mercifully, withdrew.

The esker itself is a time-ladder, inviting slow ascent. Step by step, gravel shifts underfoot—rounded stones, carried far from their origins, now loyal to this place. Each stone is a traveler without a passport, naturalized by pressure and pause. Together they hold their line, resisting erosion not by hardness alone, but by collective agreement.

From above, the ridge reveals its length, its deliberate curve. It does not hurry. It does not apologize. It simply is, a memory ridge, reminding the present that absence can be as powerful as presence. The glacier is gone, yet its handwriting remains legible.

In the nearby swamp, water pools in dark reflection. Frogs tune their throats. Sedges write vertical poetry. This is the after-ice sanctuary, where meltwater’s descendants linger and life reclaims the margins. The esker drains; the swamp receives. Between them flows a balance older than names.

To walk here is to practice a different kind of attention. The land does not reward speed. It rewards listening. The ridge asks you to follow its curve, to feel how it shapes movement, how it choreographs water, wildlife, and wandering humans alike. It is a path-without-intention, yet it guides all who encounter it.

Long after the tent is folded, after the creek continues its bent course, after the placards fade and are replaced, the esker will remain. It will continue directing water, lifting footsteps, and teaching geometry to anyone willing to notice.

Eskers and kames are the glacier’s farewell letter, written in gravel, signed by time, and left open for reading.

Click Me for the first post of this series.

You’ve captured some beautiful scenes!

LikeLike

Thank you, Kymber — Malloryville has a quiet, unassuming beauty, and it’s always gratifying to know that the photographs conveyed even a portion of that feeling.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautiful, just beautiful

LikeLike

Thank you, Sheree — I appreciate that very much. I’m glad the piece spoke to you in a simple, direct way; sometimes that quiet recognition feels most in keeping with the place itself.

LikeLike

“Land teaching water a new sentence.” – Just one of many stunning lines. Your photos and words capture content and emotion so beautifully, Michael! I feel like I was there and am the better for it.

LikeLike

Thank you, Lynne — I am gratified that line resonated with you. It was my attempt to listen closely to what the land itself was saying. Knowing that the words and photographs carried you there, and left something with you afterward, means a great deal to me.

LikeLiked by 1 person