I examined an unusual map of Florida, the contours of its familiar modern shape overlaying a vast, green expanse. The state as we know it today is crisscrossed by highways and dotted with bustling cities, but this map transported me back in time to a very different era. During the Pleistocene epoch, Florida was a wilder, untamed land, teeming with life and dominated by creatures long extinct.

Exploring Brevard (county) Museum of History and Natural Science of Cocoa Florida, I moved to the next exhibit. The air hummed in my imagination with the whispers of an ancient world. A skeletal figure loomed within a glass case – the mighty Smilodon fatalis, the sabertooth cat. Its fearsome fangs curved downward, I imagined standing face-to-face with this apex predator, feeling both awe and a primal fear.

Florida, some 11,500 years ago, was a place of significant climatic shifts. The Pleistocene epoch was characterized by repeated glaciations; however, Florida itself remained unglaciated. The climate was cooler and drier than today, and sea levels were much lower, extending the coastline outward. This ancient Florida was a mosaic of grasslands, savannas, and woodlands. Giant sloths, mammoths, and mastodons roamed these lands, sharing the territory with the formidable Smilodon.

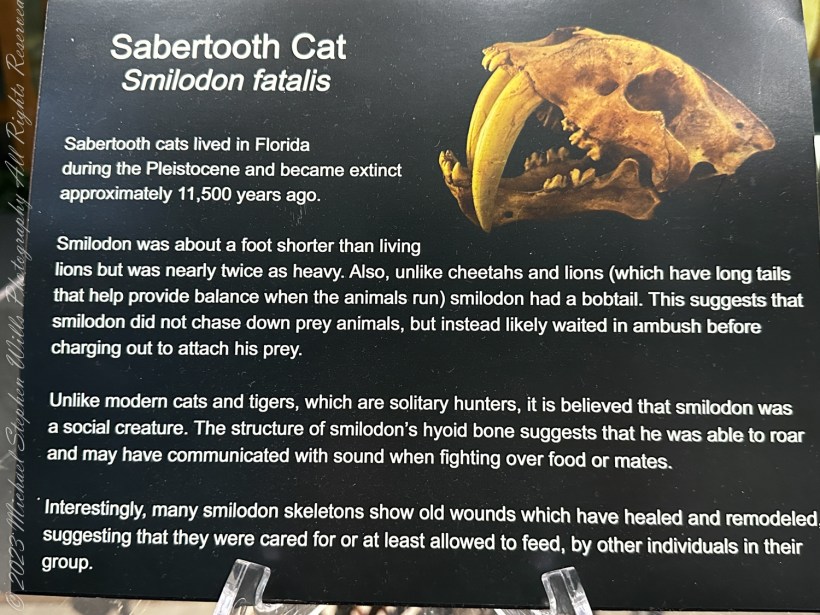

The attendant palque described Smilodon fatalis was about a foot shorter than modern lions but nearly twice as heavy. Its stocky build and powerful limbs suggested immense strength. Unlike the cheetahs and lions of today, Smilodon had a bobtail, indicating that it relied less on speed and more on ambush tactics. I could almost see it now: crouching low in the underbrush, muscles coiled, waiting for the perfect moment to spring upon its unsuspecting prey.

In the reconstructed display, the sabertooth cat’s lethal precision was evident. Its elongated canines were deadly tools designed to pierce and hold onto struggling prey. The lack of a long tail, which modern big cats use for balance during high-speed chases, suggested that Smilodon was an ambush predator. It would have hidden in the dense foliage, its mottled coat blending seamlessly with the shadows, until it launched a surprise attack.

Smilodon was not just a solitary hunter. Unlike modern cats and tigers, which often lead solitary lives, evidence suggests that Smilodon was a social creature. The plaque mentioned the structure of its hyoid bone, implying that it could roar, perhaps using vocalizations to communicate with other members of its group. I envisioned a family of Smilodon, working together to take down a mammoth or defend their territory from rivals. Their social bonds might have been strong, much like those of modern lions.

I was particularly struck by the evidence of healed wounds found on many Smilodon skeletons. These injuries had healed and remodeled over time, suggesting that these cats cared for each other. In a world where every day was a battle for survival, these acts of care and compassion spoke volumes about their social structure. Injured members were not left to fend for themselves but were likely allowed to feed off the kills of others and to be protected by their group until they recovered.

The exhibit painted a vivid picture of an ancient ecosystem. The Pleistocene flora of Florida was diverse, with vast grasslands interspersed with stands of pine and oak. The fauna was equally rich: herds of herbivores grazed the plains, while predators like Smilodon and dire wolves stalked them. This was a land of giants, where every creature had to be strong, fast, or cunning to survive.

As I stepped away from the exhibit, I felt a deep connection to this ancient world. The Smilodon fatalis was a predator and is a symbol of an era that shaped the natural history of our planet. Its bones told a story of survival, community, and the ever-changing dance of life and death.

In the quiet of the museum, surrounded by the echoes of the past, I was reminded of the fragility and resilience of life. The sabertooth cat, with its fearsome fangs and powerful build, was a testament to the incredible adaptability of life on Earth. Though it has long since vanished from our world, the spirit of Smilodon fatalis lives on in the bones it left behind and in the stories we tell about the ancient world it once ruled.

I’m glad I did not live in Florida in their day! 😊

LikeLiked by 2 people

There is evidence of humans inhabiting Florida around 11,500 years ago. One of the most significant sites providing this evidence is the Page-Ladson site, located in the Aucilla River in the Florida Panhandle.

This underwater archaeological site has yielded artifacts and fossils dating back to around 14,550 years ago, which suggests human activity in Florida even earlier than 11,500 years ago. Excavations have uncovered stone tools, including a biface and a scraper, as well as mastodon bones with cut marks, indicating human processing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! Very interesting for sure. Little by little, as more and more discoveries are made, maybe the books on natural history, anthropology and archaeology will be re-written. It seems like we’ve (humans) have been around longer than we ever thought. Thank you MIchael.

LikeLiked by 1 person

In the Americas the dates have certainly pushed back. Good to hear from you, Francisco.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Michael. Archaeology is indeed fascinating! All the best!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The original Florida Panther? Not everyone may get my hocky reference😊 Maggie

LikeLiked by 1 person

The southernmost team of the NHL….

Ah, the Florida Panther—skating into history long before hockey sticks! 🏒😉 Great reference, Maggie! Thanks for the chuckle!

LikeLiked by 1 person