Learning the Shape of a New Building

I first noticed the building from above.

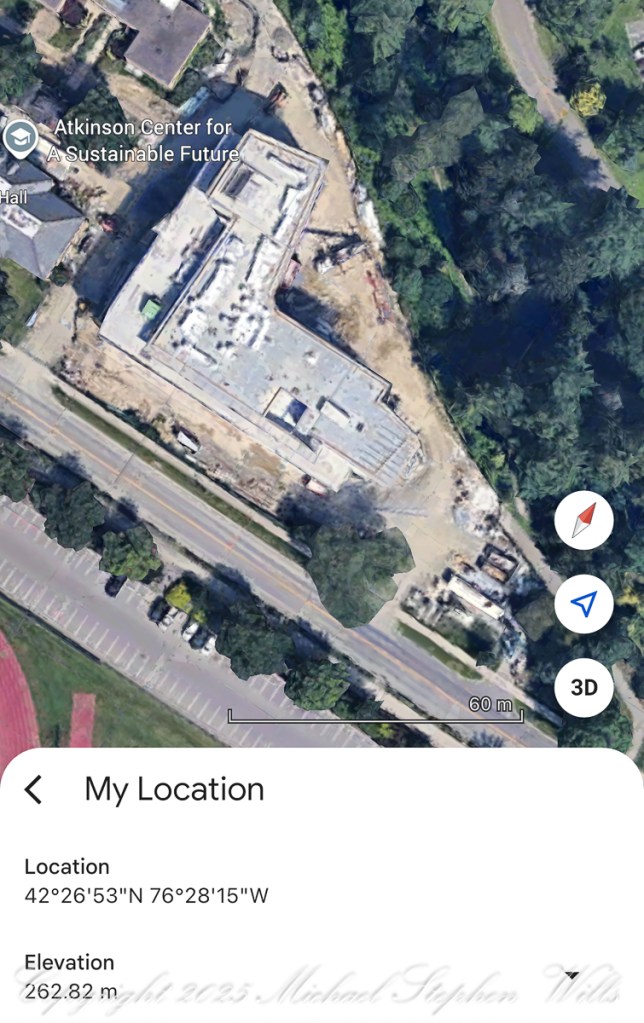

Not in person—on my screen, late at night, when I should have been revising a draft and instead opened Google Earth the way some people open a window. There it was, just off Tower Road, close to Stocking Hall, pale and newly settled into the slope. From that height it looked careful rather than confident, as if it had arrived recently and was still deciding how much of itself to show.

I remember thinking: good placement on a former triangular parking lot. Enough distance from the older buildings to breathe, close enough to feel included. The hill does most of the work. You can see that even from an overhead height.

The next morning I walked there.

Across the open field the building didn’t announce itself. Trees intervened—pines, bare hardwoods—so that it came into view in pieces: a curve of metal, a long line of glass, brick holding the ground. It felt less like approaching a destination than like gradually realizing you were already there. I liked that. Buildings that reveal themselves all at once tend to exhaust me.

The slope matters. You feel it in your legs as you walk, and the building seems to acknowledge it, stretching rather than standing tall. It does not pretend the land is flat. It follows the descent toward the creek, toward the older geological story underneath all of us.

Up close, the materials settle my attention.

Brick at the base—solid, Cornell-familiar, not trying to reinvent anything. Above it, bands of weathered metal curve gently, already carrying the muted browns of fallen leaves, old stone, and stream-worn shale—colors long familiar to the slopes and ravines that shape this campus. They look as though they have agreed to age, which feels like an underrated design choice. The glass holds the sky without insisting on transparency. Some days it reflects trees so clearly that the building nearly disappears into them.

I stop near the windows longer than I intend to. The view steadies me. The hillside, the trees, the quiet persistence of winter light. My notebook stays closed for a few minutes. No one seems to mind.

Inside, the building does not behave like a department.

That is the first thing I notice once I begin using it regularly. No single discipline claims the space. Offices and meeting rooms feel provisional, lightly held. Conversations drift. Someone from engineering crosses paths with someone from policy. A food systems researcher borrows a chair from a planner. No one looks lost.

It helps to remember who gathers here. The building hosts people from many parts of the university, each arriving with partial expertise, incomplete questions.

| Cornell College / Unit | Areas of Engagement |

|---|---|

| College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (CALS) | Food systems, agroecology, climate resilience |

| College of Engineering | Energy systems, materials, infrastructure |

| College of Arts and Sciences | Earth systems, ecology, human dimensions |

| SC Johnson College of Business | Sustainable enterprise, supply chains |

| College of Architecture, Art, and Planning (AAP) | Urban resilience, adaptive design |

| Cornell Law School | Environmental law and governance |

| Public & Global Affairs | Climate policy, diplomacy |

I keep this list taped inside my notebook. It reminds me that no one here is meant to arrive fully formed. The building expects us to be unfinished.

There is a quiet confidence in how the place is run. Systems hum discreetly. Heat holds steady even when the weather rips. Somewhere nearby, unseen, a generator waits, a reassurance. Work continues. Conversations do not end mid-sentence. I think about this more than I expected to. Stability has become a form of generosity.

On certain afternoons I walk the exterior again before heading home.

The curves soften what could have been institutional. Corners ease into one another. Nothing feels sharp. The building does not posture or instruct. It listens. It seems content to let weather, foot traffic, and time finish the job.

I have overheard visitors describe it as “restrained.” I think that is right. It does not wear sustainability as an emblem. It does not ask to be admired. It offers something quieter: space to think without being hurried, to talk without being territorial.

From some angles it nearly disappears into the hillside. From others it asserts itself just enough to be useful. That balance feels intentional, and also rare.

When I sit near the glass and look out, I sometimes imagine the building learning us in return—our habits, our pauses, the way we linger in doorways when a conversation matters. It seems designed for that kind of noticing.

If I were forced to describe it the way a realtor might, I would say it is well built in all the ways that matter. The structure is sound. The site is excellent. The materials will age well. But what I would mean is something less technical.

It is a building willing to wait.

Seen from above, it is still new.

Seen from the field, it is already settled.

Seen from inside, it feels patient.

That patience makes room—for uncertainty, for collaboration, for the long work that does not resolve quickly. I think that is why I keep returning, even on days when I do not strictly need to be there.

The building does not ask what I am producing.

It asks only that I stay awhile.

And for now, that is enough.