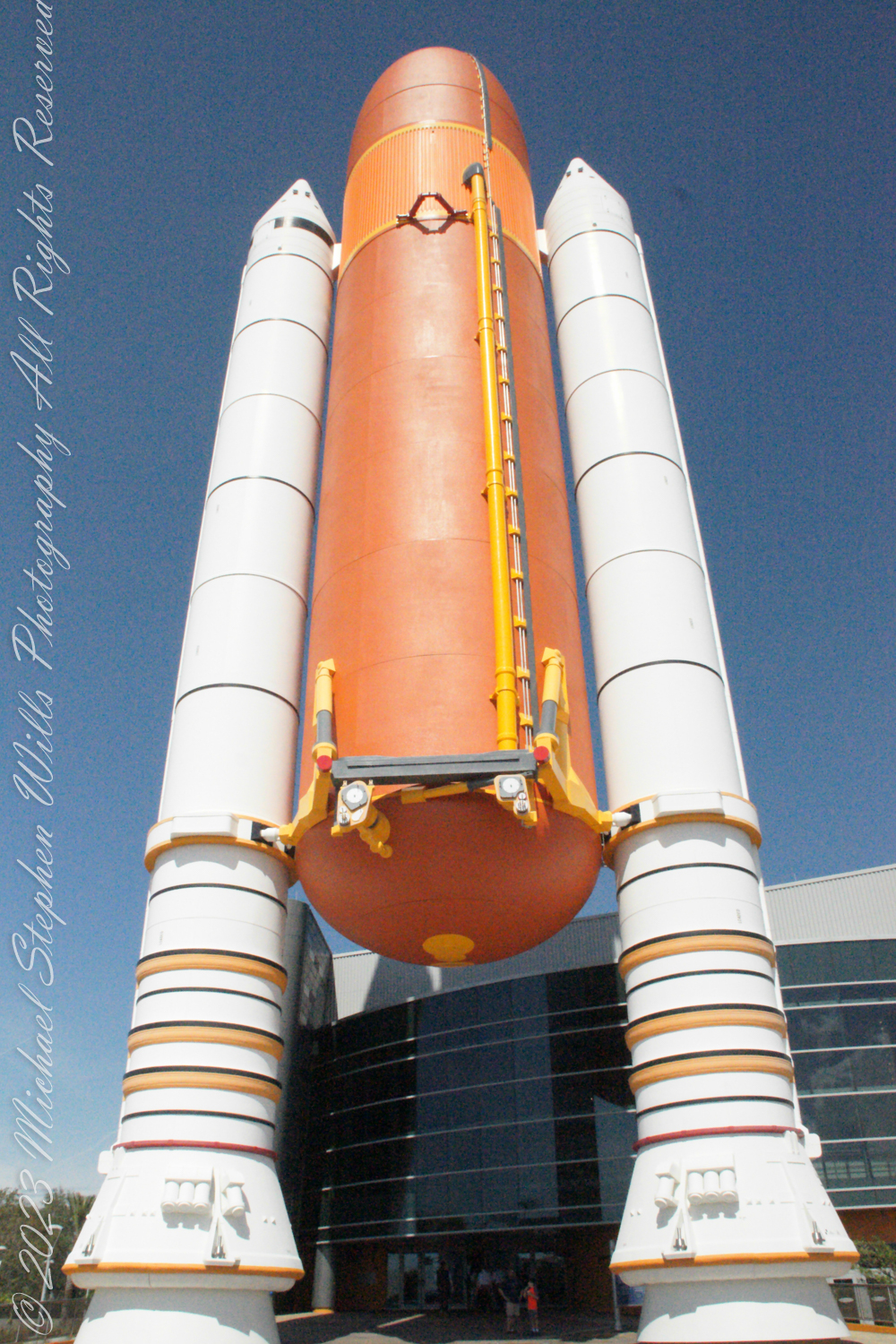

The Space Shuttle, officially known as the Space Transportation System (STS), was an iconic spacecraft operated by NASA from 1981 to 2011. It consisted of an orbiter with wings for landing like an airplane, external fuel tanks, and solid rocket boosters. With its multiple missions ranging from satellite deployment to the construction of the International Space Station, the Space Shuttle was a symbol of human ingenuity in space exploration. Central to the Shuttle’s success was its navigational system, which combined state-of-the-art technology of its time with human expertise.

The navigation of the Space Shuttle was a complex orchestration involving both internal and external elements designed to work in the harsh environment of space. The photographs attached illustrate some of the external navigational elements.

External Navigational Elements

The external surface of the Space Shuttle, as seen in the following images, was covered with thousands of thermal protection system tiles. These tiles were crucial not only for protecting the Shuttle from the extreme temperatures experienced during re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere but also housed the critical sensors for navigation.

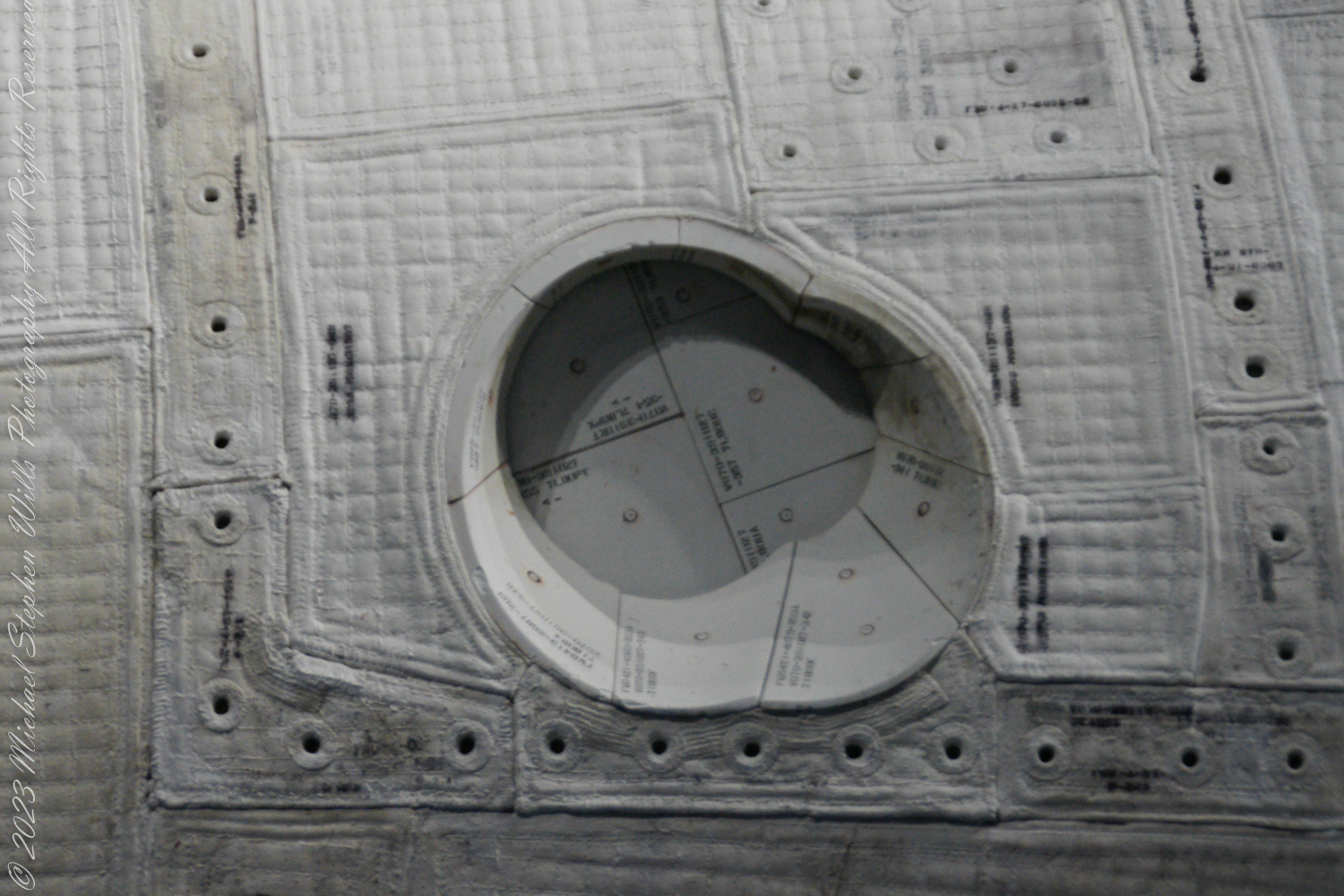

One of the key external navigational features was the Reaction Control System (RCS), seen as clusters of small circular ports below the cockpit windows. The RCS was composed of small thrusters that could fire in short bursts to adjust the Shuttle’s orientation or speed in space. This system was vital during the maneuvers in orbit, such as satellite deployment, docking with the International Space Station, and repositioning for re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere.

Internal Navigational Elements

Internally, the Space Shuttle featured a complex avionics system. The following image depicts part of the orbiter’s internal structure with an array of docking mechanisms and sensor housings. The round port, surrounded by a ring of bolts, is likely an interface for the Orbiter Docking System, used for rendezvous and docking with the International Space Station.

The following image shows a close-up of one of the orbiter’s windows, surrounded by reinforced panels. Each window was crucial for manual navigation, allowing astronauts to visually confirm their orientation and position relative to celestial objects and the Earth. The windows were also essential during landing, which was conducted manually by the Shuttle’s commander.

Navigational Avionics

The Shuttle’s navigation was supported by an avionics system that included inertial measurement units (IMUs), star trackers, and various other sensors. IMUs tracked the Shuttle’s position by measuring its velocity and direction, while star trackers used sightings of known star patterns to calibrate the Shuttle’s orientation in the vastness of space.

The navigational computers onboard processed data from these systems to maintain the trajectory and manage the Shuttle’s multiple systems. The computers were capable of autonomous operation, although astronauts were trained to take over manually if necessary.

Ground Support and Telemetry

In addition to onboard systems, navigation relied heavily on ground-based tracking and data relay satellites. The Shuttle communicated with NASA’s Mission Control Center, which monitored its position and trajectory, providing updates and corrections as needed. Telemetry data sent back to Earth included velocity, altitude, and engine performance metrics, which were crucial for ensuring the Shuttle’s safe passage in and out of orbit.

In Summary

The Space Shuttle’s navigational capabilities were a testament to the integration of technology and human skill. From the RCS ports on its tiled exterior to the sophisticated avionics inside, every component played a critical role in the Shuttle’s missions. This harmonious blend of internal mechanisms and external sensors, complemented by vigilant ground support, enabled the Space Shuttle to navigate the cosmos and return safely home, mission after mission.