The breeze off Cayuga Lake was lively, stirring the willows and creating waves that rippled across the water’s surface as we arrived at Stewart Park. For Pam, this day marked a significant milestone: her first therapeutic walk since undergoing total hip replacement surgery. The park, located on the outskirts of Ithaca, New York, had long been a place of peaceful walks and scenic reflection for us, but on this day, it took on new meaning. The pathways and views we had enjoyed over the years now served as the backdrop for Pam’s journey of recovery.

As Pam began her walk, using her walker for support, the air felt crisp with the late-summer breeze. She moved carefully along the paved path, her steps steady but measured. The sight of her, framed by the grand trees lining the park, was a testament to the resilience and strength she had displayed throughout the weeks following her surgery. The park’s beauty offered a sense of calm that seemed to support her determination, as though nature itself was encouraging her every step.

Stewart Park, with its sweeping views of Cayuga Lake and towering willows, had always been a special place for us. Over the years, we had spent afternoons such as this sailing the lake’s expansive waters. We ventured out to let the wind carry us across the lake. As Pam walked, we reminisced about those times—how we would navigate the gusty winds that filled our sails, steering into the waves with a sense of adventure. “This wind reminds me your calls to ‘control the jib!!’,” Pam said, smiling as we remembered the thrill of maneuvering the boat to dock.

On days like those, the lake was unpredictable, much like Pam’s journey through recovery had been. Yet, whether on the water or facing the challenges of healing, Pam had always shown a quiet, steadfast determination. Just as we had learned to adjust the sails to accommodate the changing wind patterns, Pam had adapted to her new circumstances, tackling each step of her rehabilitation with grace.

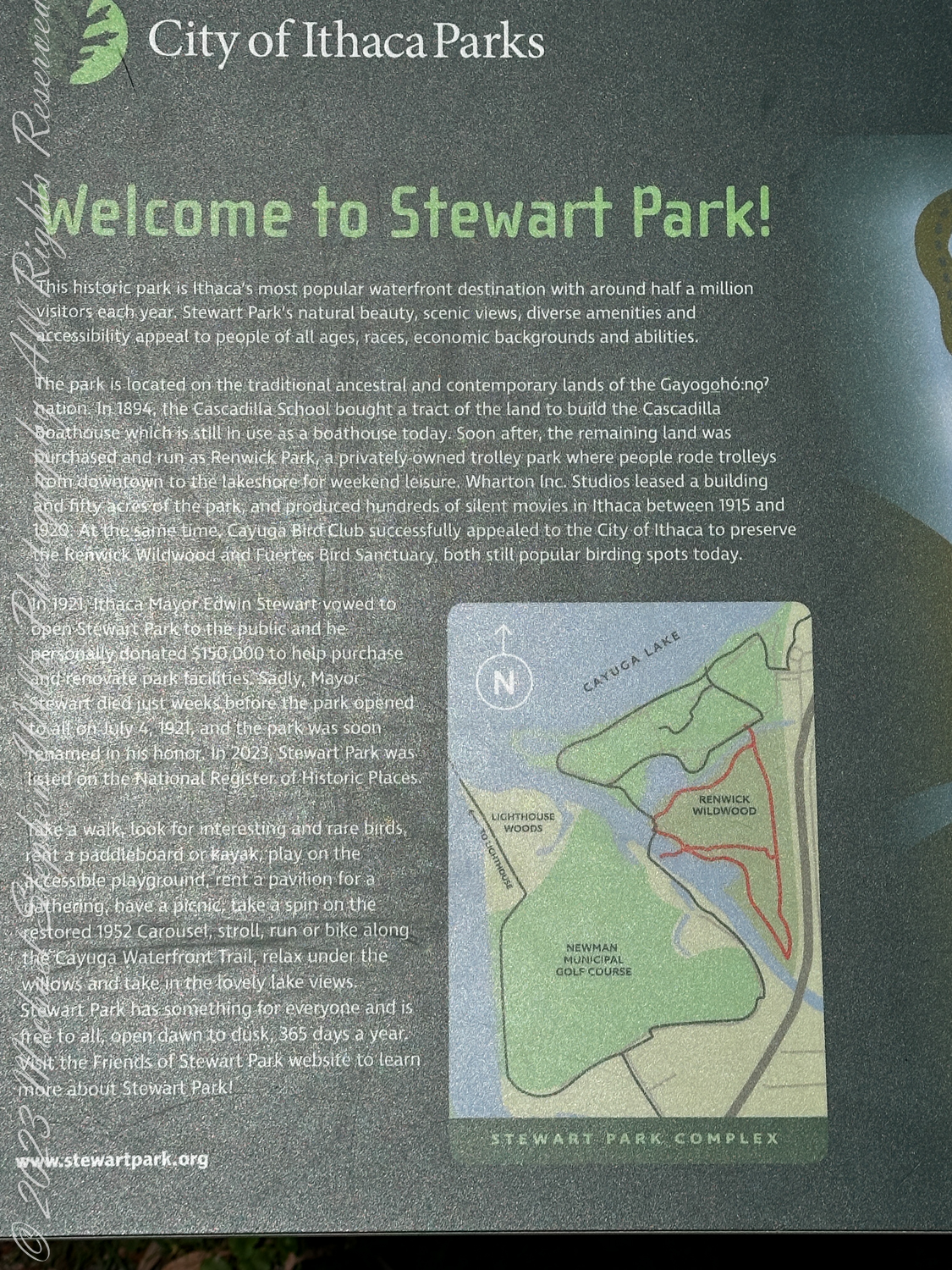

We paused at one of the informational signs along the path. The sign detailed the park’s history, noting that it sits on the ancestral lands of the Gayogo̱hó꞉nǫ’. Originally developed in 1894 for the Cascadilla School’s boathouse, the park had undergone many transformations before becoming the public space it is today. The sign spoke of Mayor Edwin Stewart, who had donated $150,000 to help purchase and renovate the park’s facilities, only to pass away weeks before its official opening in 1921. In 2021, the park was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, a testament to its enduring role in the community.

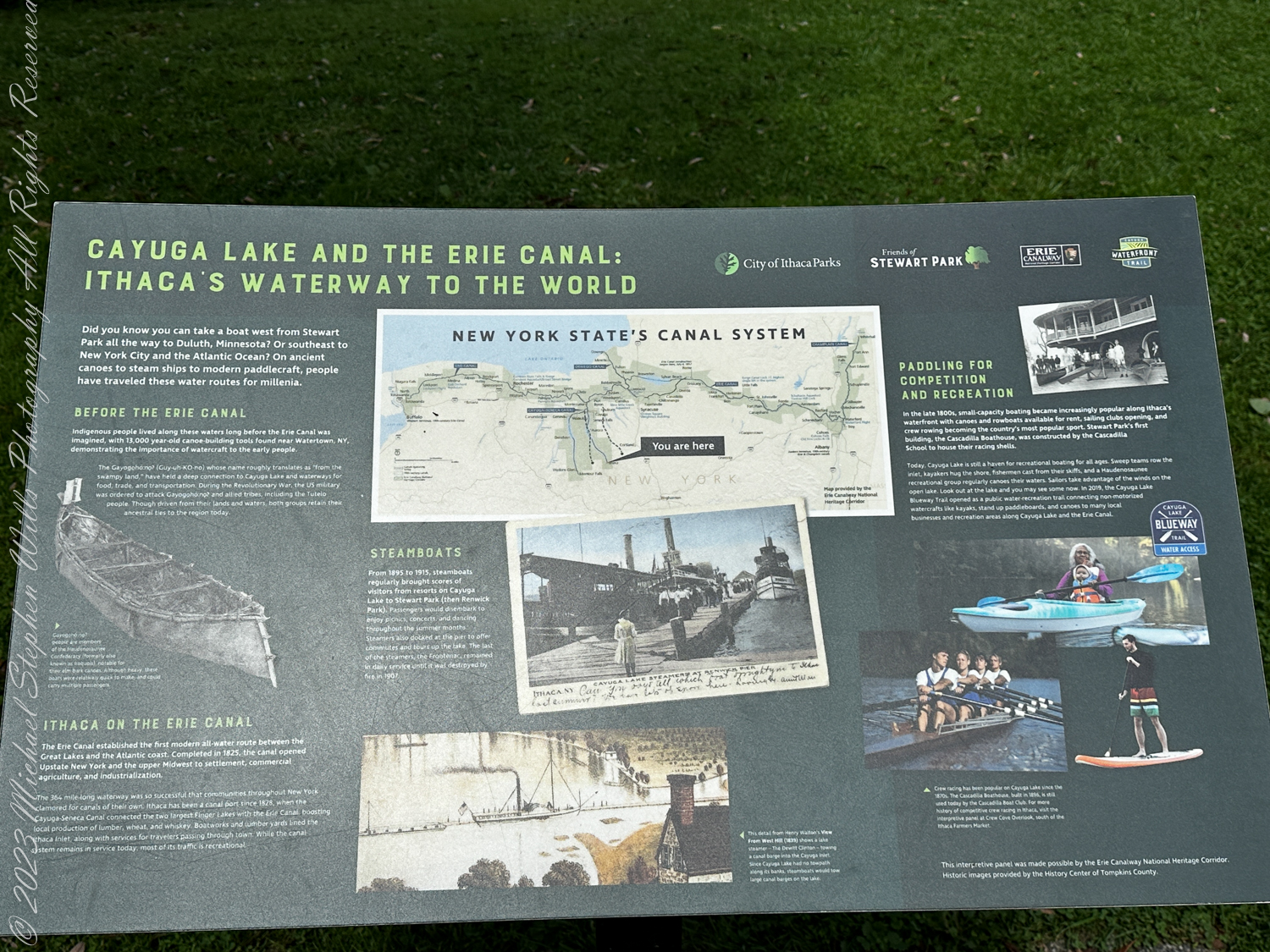

Did you know you can take a boat west from Stewart Park all the way to Duluth, Minnesota? Or southeast to New York City and the Atlantic Ocean? On ancient canoes to steam ships to modern paddlecraft, people have traveled these water routes for millenia.

Before the Erie Canal

Indigenous people lived along these waters long before the Erie Canal was completed in 1825. In 1790, a dugout canoe was found near Elmira, NY, demonstrating the importance of waterways to the early people.

The Cayuga/Seneca Gayogo̱hó꞉nǫʼ who lived here for nearly a thousand years used the lake and rivers to transport people and goods. In the 1600s, French explorers reported meeting the Gayogo̱hó꞉nǫʼ as they traveled east along these waterways. Canoes and later watercraft helped settlers move people, goods, and ideas, transforming upstate New York. With only one lock, the lake’s water level would rise and fall, but goods still needed to be portaged, or moved over land. As the first commercial waterway in the US, the Erie Canal used river systems, canal channels, and lakes to connect New York’s inland towns to world markets.

ITHACA ON THE ERIE CANAL

The canal established the first modern all-water route between the Great Lakes and the Atlantic. Completed in 1825, the canal opened Upstate New York and the upper Midwest to settlement, commercial agriculture, and industry.

The southernmost port of the canal was at Cayuga Lake, near present-day Route 90, where steamboats ferried passengers and freight to and from Ithaca. Products like salt from Syracuse, wood from the region, and coal from Pennsylvania were loaded onto canal boats for shipment to New York City or via Buffalo, to the upper Midwest.

After more than 200 years of service, the canal has evolved into a water route that is primarily used by small boats for recreation. In 2017, the NYS Canal Corporation rebranded the canal as a recreation destination.

As Pam read the sign, she reflected on how the park’s evolution mirrored her own journey. Like Stewart Park, which had undergone multiple transformations over the years, Pam was in the midst of her own renewal. Her new hip, like the park’s renovations, represented a fresh start, a return to activity, and a promise of more days spent outdoors, enjoying the natural beauty that had always brought us peace.

Continuing along the path, we passed several benches nestled beneath the graceful willows, their branches swaying gently in the breeze. Pam took a moment to rest on one of the benches, her eyes focused on the vast expanse of Cayuga Lake. The view stretched toward the distant hills, where the clouds and sun played together, casting ever-shifting patterns of light across the water. For a brief moment, it felt like we were back on our sailboat, riding the waves and allowing the wind to guide us toward new horizons.

As we made our way back along the path, the tall willows swaying and the sound of the waves lapping at the shore, I couldn’t help but feel gratitude. Stewart Park had always been a place of calm and reflection, but on this day, it became a place of healing. Pam’s steps, though slow and deliberate, were filled with the same strength and grace she had shown throughout her life.

The park’s beauty, the history we had shared here, and the memories of our time spent sailing on Cayuga Lake all came together to create a sense of peace. Pam’s recovery journey was far from over, but her progress was undeniable. As we looked out over the lake one last time before heading home, the water shimmered in the sunlight, promising more adventures to come.

Stewart Park, with its windswept trees and timeless views, would forever be tied to this day—Pam’s first steps toward reclaiming her mobility, set against the backdrop of a place that had long been part of our shared story. It was a day filled with hope, strength, and the quiet knowledge that, like the wind, life would continue to move us forward, no matter the challenges.