It was the kind of overcast morning that seems to cradle the island in a blanket of mist, a gentle hush falling over the land as though even the Atlantic held its breath. Pam and I had arrived by ferry at Kilronan, the main settlement on Inishmore (Inis Mór), the largest of the Aran Islands nestled in Galway Bay. There, amid the bustle of arrivals and greetings, we found our driver—a wiry, weather-worn man with a soft brogue and kind eyes—and his horse trap, a simple two-wheeled carriage with room enough for three and the sounds of hooves to accompany our journey.

We set out up Cottage Road, the stone-paved track winding westward from the harbor. The sea fell away behind us as we climbed, a gray shimmer stretching to the hazy outline of Connemara’s mountains on the far side of the bay. Our destination was the dramatic cliffside ringfort of Dún Aonghasa, a place older than memory. But it was the unexpected moments in between—the ones not printed in guidebooks—that linger longest in the mind.

As we rounded a bend flanked by low stone walls, wildflowers blooming defiantly in the cracks, our driver pulled the reins gently and pointed with his crop.

“There,” he said, nodding ahead, “is a fine example of a traditional Aran cottage.”

And there it was—a vision from another time. The thatched roof curved softly like a that blanket itself, straw golden against the brooding sky. The walls were whitewashed to a perfect matte sheen, gleaming in spite of the cloud cover. A crimson door and two window frames punctuated the front façade like punctuation in a poem. Just to its right, set further back on the hill, stood a tiny replica of the same cottage, identical in every feature. I blinked, half believing it was an illusion.

Click the link for my Getty IStock photography of the Aran Islands

We only stopped briefly—it was a private residence—but the sight of it left a kind of imprint. I turned in the trap seat to keep it in view as long as I could. The cottage was perfectly placed, facing Galway Bay with a commanding view. I imagined the light pouring across the line of mountains, catching the glint of sea and sky.

“There’s a name for that finish,” I said, recalling something I’d read, “whitewash, or lime paint.”

Our driver nodded. “That’s the old way. Made from slaked lime. We’d call it ‘whitening’ when I was a lad.”

Whitewash differs from paint in the most elemental of ways. It becomes part of the stone, absorbed into the very surface. Like a memory of bone. And yet, it requires care. Apply it to a wall not properly cleaned or moistened, and it flakes, pulls away like a broken promise. But done right, it lasts, breathes with the building.

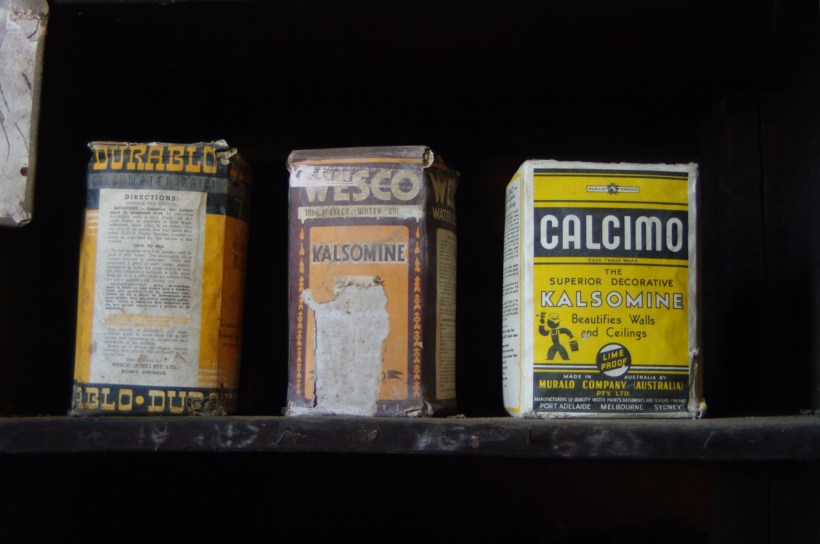

Upon our return, researching “whitewash,” if found this photograph from the Yarloop railway workshops Yarloop, Western Australia. There, on a shelf, where three old boxes sat like relics: DURABLO, WESCO, and CALCIMO. All contained kalsomine—the powdered form of lime paint. CALCIMO promised to “beautify walls and ceilings” and was proudly marked “LIME PROOF.” There was something quietly heroic in that. Lime-proof, as though against time itself.

Looking at the box of Calcimo, a product of the Murabo Company of Australia, I was struck by how far the tradition had traveled. From island cottages in the Atlantic to distant corners of the Southern Hemisphere, the language of whitewash—of simplicity and purity—had touched the world.

We returned by the same road, past that same cottage, the small one still keeping watch beside it like a child beside a parent. And I knew then that the islands hadn’t just given me sights—they had offered stories, silent ones written in thatch and stone, in lime and wind.

Sources for this post: search wikipedia for “White Wash”. White wash photo author: Wikipedia commons user Gnangarra

That ability of whitewash to meld with the stone’s an interesting detail. I didn’t know that.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I enjoy writing blogs in part for the research, discovering interesting new facts along the way. It was news to me, as well. A well tested technology.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have often wondered about whitewash. Does it last longer than paint? Prevent discoloring or mold? Preserve the exterior?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Great questions, ekurie. Thanks for visiting and reading.

LikeLike

Something new I learned, thanks.

LikeLiked by 2 people

my pleasure, Laleh.

LikeLiked by 1 person

❤️

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m enjoying your lovely photographs from your May trip to Ireland!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, I never knew there was a difference between whitewash and white paint!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Now you have a new level of detail for your art, Emma.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting information about whitewash.

Well-written post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Nesfelicio! I’m so glad you found the details about whitewash interesting—it’s a humble material with quite a bit of history behind it. I appreciate your kind words about the post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Irish dún that means ‘fortified place’ is etymologically the same as English down, which ended up denoting the direction one goes in leaving a [high] fortified place. English town, borrowed from Celtic, is also the same word.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Steve—what a fascinating etymological thread! It’s remarkable how language carries the memory of place and purpose. The descent from dún to down adds a poetic echo to those windswept heights of Inishmore. I appreciate the added depth your comment brings to the post.

LikeLike

Beautiful

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Sheree—so glad the post spoke to you. Your visits and kind words are always appreciated!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re very welcome Richard

LikeLiked by 1 person

We learned a lot about whitewashing in Spain and Portugal this year, having learned it from the Moors, who learned it from even older civilizations. But we have also seen it in parts of South America too, brought over by the Spanish I assume. It makes the homes look so much more charming.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Maggie—what a rich trail of history you’ve followed! It’s fascinating how whitewash traveled across continents and cultures, carrying both practical value and aesthetic charm. I love how it connects humble homes from Inishmore to Iberia and beyond, each with its own story written in lime.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for sharing this lovely story, Michael Stephen.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, Jet. I’m glad you enjoyed the story—it means a lot to share these memories and connect through them. Your kind words are truly appreciated.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There’s something so timeless and romantic about that cottage. The photo could be hundreds of years old and it certainly harkens back to seemingly simpler times. Beautiful. I didn’t know about “whitening” as a specific technique. Thanks for the lesson, the poetry of the place, and the photo.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, Diane. That cottage seemed to hold time still, didn’t it? I’m so glad the image and words brought that sense of quiet romance to you. The whitening—or whitewashing—tradition runs deep in places like Inishmore, part preservation, part poetry. I always appreciate your reflections.

LikeLiked by 1 person