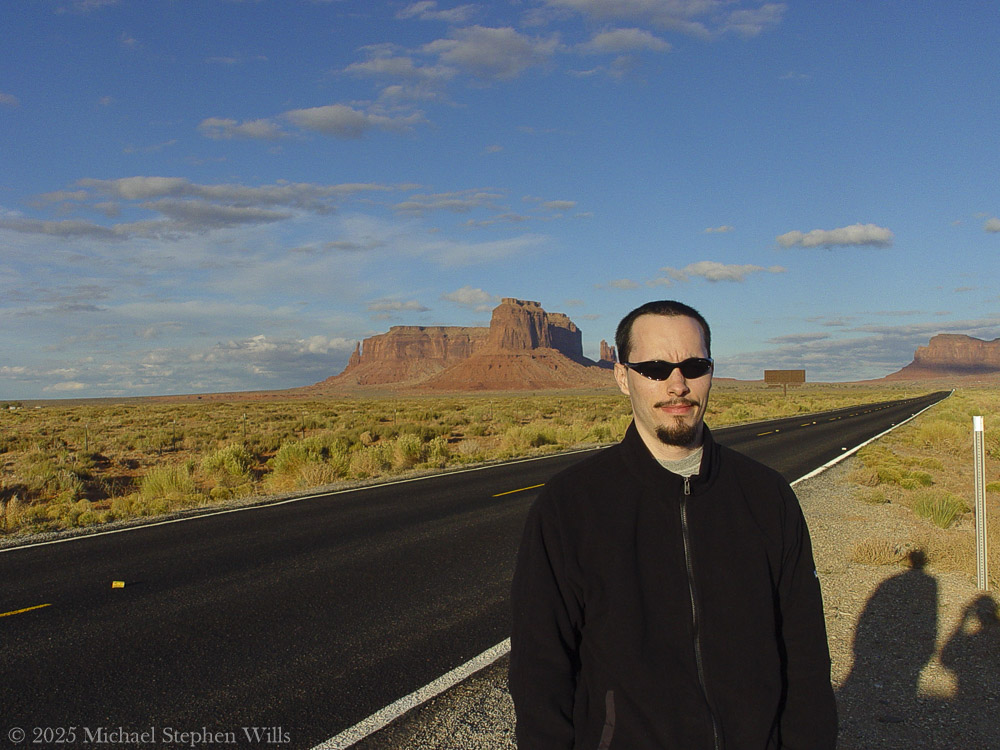

In the golden hush of this November sunset, Monument Valley stretches before us – an endless desert plain punctuated by towering red rock sentinels. The sky is vast and translucent blue, as a pale three-quarter moon rises silently above a solitary spire of sandstone. That spire is known on maps as Big Indian, a stone pillar glowing russet in the low sun. It stands apart from the mesas, its silhouette uncanny against the evening sky. In this serene moment, the land feels alive with presence. And the name “Big Indian” lingers in the air, raising quiet questions about what we call this place – and what it truly is.

From a distance, the spire does suggest a figure: tourists are told to squint, tilt their heads, and “see” the profile of a Native face gazing outward. One can imagine the first person to name it must’ve been a bored prospector, half-delirious from the heat after a lunch of canned beans, declaring: “I swear that rock looks like Uncle Joe in a feathered headdress.” And so the name stuck – a geological Rorschach test gone slightly colonial.

These whimsical titles – Totem Pole, Stagecoach, Big Indian – come not from the land, but from a long habit of outsiders labeling what they didn’t fully understand. “Big Indian” is particularly layered. The term “Indian” itself was born from Columbus’s navigational misfire, mistaking the Caribbean for Asia and its people for “Indios.” The Diné, the people who have lived here for centuries, never called themselves that. So this towering formation now bears the echo of a 15th-century directional blunder —like a name tag on the Sphinx that reads “Buckeye” because someone once thought Egypt was in Ohio. It’s a reminder: names given in haste can cling for centuries, even when they miss the mark entirely.

But beyond the names imposed by mapmakers, the spire simply is, in all its silent grandeur. In Diné lands, this valley has a different name: Tsé Biiʼ Ndzisgaii, often translated as Valley of the Rocks. In the Navajo tongue the name literally evokes “rock within white streaks around” – referring to the light bands of sediment that ring the red buttes. Those pale streaks wrap the spire like faded paint, remnants of ancient layers of earth. Here the Diné language whispers a description born of the land itself, unlike the English names that often project an outsider’s story. Tsé Biiʼ Ndzisgaii speaks to the truth of the place: stone and light, strata and shadow. As the sun lowers, you can actually see those whitish bands catching the last glow, encircling the butte like old memory. The Diné name honors what the eye sees – the layered geology – rather than imposing an unrelated label. This spire and its neighbors were not built by human hands, though their sheer stature can feel like architecture of the gods. Millions of years of natural artistry shaped Monument Valley.

Long before any person walked here, this land was a low basin collecting sediments. Layer upon layer of sand and silt hardened into rock, and a slow uplift in the earth heaved the basin into a plateau. Wind and water became patient sculptors over the last 50 million years, carving the plateau and peeling away the softer material. What remains today are the skeletal monuments of that erosion: buttes, mesas, and spires rising up to a thousand feet above the desert floor. Each is made of stratified stone – the broader bases of red shale and sandstone, and a cap of harder rock that resists the elements. Big Indian’s sturdy pedestal and slender crest tell this story of layered resilience. In the red-orange rock, oxides of iron tint the cliffs a deep rust, while streaks of black manganese oxide – “desert varnish” – trace down their sides like natural paint. Time and the elements have sculpted a masterpiece here.

Standing at its foot, one needs imagine the immeasurable ages of sun and storm that chiseled this lone tower from the earth. And yet, facts of geology alone fail to capture the spirit one feels in Tsé Biiʼ Ndzisgaii. The Diné know that spirit well – this valley is sacred to the Navajo Nation. To them, these colossal rocks are alive with meaning. The people have lived and wandered among these mesas for centuries, blessing the land with their stories and prayers.

In Navajo cosmology, the landscape itself is imbued with life and purpose. The buttes are often seen as ancestors, guardians, or holy figures watching over the People. For example, the famous twin buttes called the Mittens are said to be a pair of spiritual beings – one male, one female – forever facing each other across the valley, protecting and balancing the land. Another hulking mesa, Sentinel Mesa, is known as a “door post” of the valley, a guardian at the entrance, paired with another butte as the opposite door post. The valley, in the Diné way of seeing, resembles a great hogan, a home blessed by the gods: the mesas at its threshold are like the posts of a doorway, and a butte called The Hub is imagined as the central fire hearth of this immense home.

In this way, the Diné landscape is a living, storied environment. Even the spindly formations carry sacred narrative. Seven miles southeast from Big Indian stand slender pinnacles known to the Navajo as Yei Bi Chei, named for the masked spiritual dancers who emerge on the last night of a winter healing ceremony.

Each dawn, as the first light breaks over the mesas, it’s said the Navajo families come out of their hogans to greet the sun with prayers – their doorways always face the east to receive blessings of the day. In the same way, the great stone hogan of Monument Valley opens eastward, with its door-post buttes and its eternal fireplace. In Diné worldview, earth and sky are intertwined with their lives; they speak of Mother Earth from whom they emerged and to whom they owe care. Here in Monument Valley, it is possible to feel that harmony – the sense that every column of rock, every whispering juniper shrub, every beam of sunlight and moonrise is part of a whole living tapestry.

We watch as the moon climbs higher above the Big Indian spire, its silvery light softening the rock’s hard edges. This place has known many names and will outlast many more. The Paiute people who roamed here before called it “Valley Amid the Rocks” and wove myths of gods and giants into its features. Later came the labels of explorers and filmmakers: Monument Valley, a monumental canvas for Western legends. And of course, the simplistic tag Big Indian for this lone rock – a name that says more about those who coined it than about the land itself.

Names, in the end, are stories we tell about the world. The colonial names imposed here are like brief echoes across the ages, while the Diné stories run deep as the red earth. The Diné prefer to call themselves Diné – meaning “the People”– and they call this land by names that describe its true character. I imagine that to the People, this spire might be thought of not as an “Indian” at all, but perhaps as a sentinel or an old friend standing watch. Its Diné name, if it has one, would likely emerge from its form or its role in a story, spoken with reverence.

As dusk turns to twilight, an immense peace settles. The monolith before me is no longer just Big Indian on a map; it is an ancient entity shaped by time and honored by generations. In the silence, we can almost hear the land speaking in the old language – telling of how it was born from oceans and sand, how it saw the first people wander through, how it endures through centuries of memory. The rock shares with us a moment beyond names: just the whisper of wind, the glow of moon, and a feeling of connection and wonder. This is Monument Valley, Tsé Biiʼ Ndzisgaii, in all its truth. In this contemplative dusk, I bow to the tower of stone, misnamed yet never truly defined by that misnomer. It remains what it has always been – a creation of earth and spirit, a witness to history, a source of humble awe. Tuning to leave, I softly speak a word of thanks – Ahéheeʼ – grateful to have listened, if only briefly, to the sacred voice of the valley.

Bibliography

Encyclopædia Britannica – Tribal Nomenclature: American Indian, Native American, and First Nation britannica.com (origin of the term “Indian” as a colonial misnomer)

Navajo Nation Parks & Recreation – Monument Valley (Tsé Bii’ Ndzisgaii) navajonationparks.orgnavajonationparks.org (official site detailing Monument Valley’s geology and formation)

Robert S. McPherson – Monument Valley. Utah History Encyclopediauen.orguen.org (history, geology, and indigenous lore of Monument Valley)

Aztec Navajo County – Monument Valley PDF Guide aztecnm.comaztecnm.com (descriptions of formations, including Navajo perspectives on their meanings and names)

Navajo Word of the Day – Tsé Biiʼ Ndzisgaii navajowotd.com (explanation of the Navajo name for Monument Valley, meaning “white streaks in the rocks”)