Path well trodden through the centuries since.

Click any pic for a larger view, in a new tab, or a slide show. When using WordPress Reader, you need to open the post first.

Click Me for the next post in this series.

Path to the late Bronze Age

Path well trodden through the centuries since.

Last views from Kinsale, County Cork

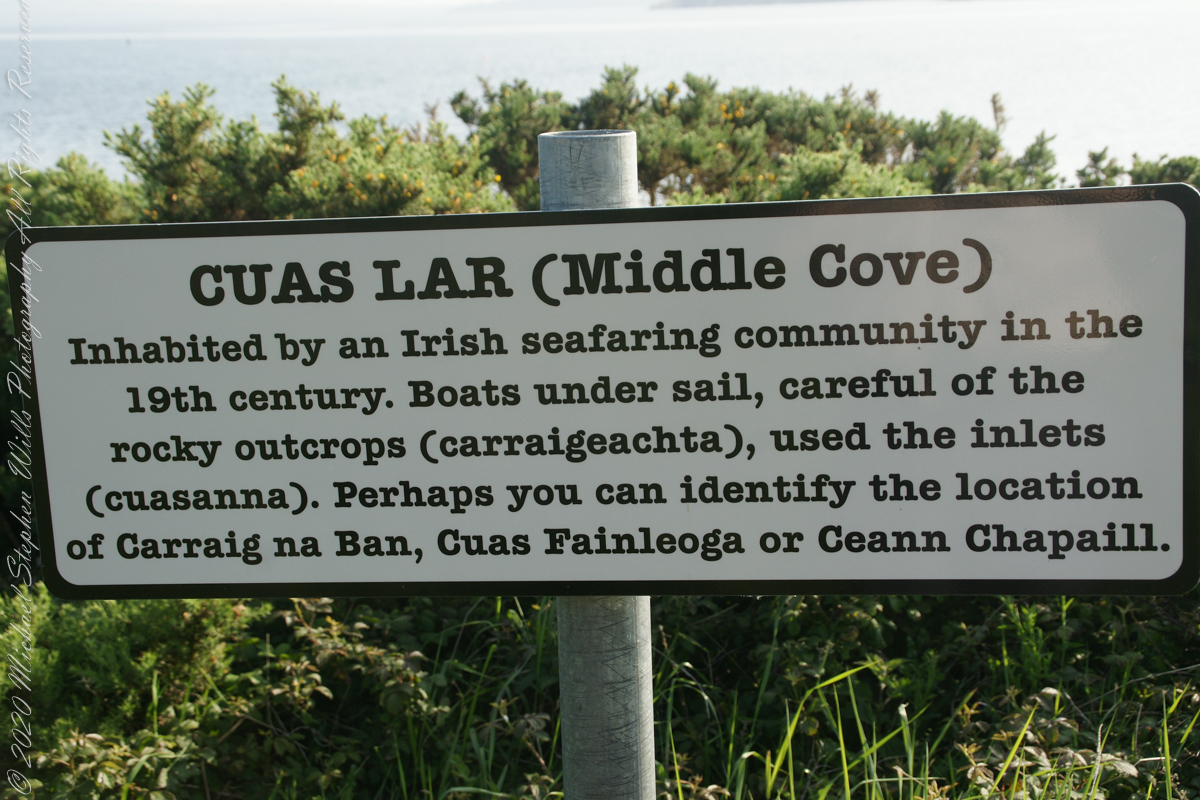

The view referred to by placard is to the right. The Old Head of Kinsale is the distant landform, looking right to left, is the portion that drops off to the ocean.

Here is a Google Maps screen capture showing the relationship of our position (the unnamed red drop-pin) on the right, and the Old Head of Kinsale landform, seen below the lable “Ballylane.”

Here are the views looking toward the Celtic Sea, the Old Head of Kinsale and the cliffs at our feet.

This cemetery is unmarked on the maps I use.

Here is a Google Earth view of our walk, the red line. The view is looking east from above the former “de Courcy family parkland.”

Old and New Forts

As Pam and I past the scenes of bucolic reverie this sign drew us back to the past. The reference to de Courcy is as a family of invading Normans. John de Courcy, without the King’s permission, launched an 1176 AD invasion of northeastern Ireland, what is now County Down, as an ultimately failed land grab. The history is murky, though apparently John de Courcy’s son Miles acquired the land referred to in the placard through the English King Henry II, awarded to Miles’ thieving, murderous Norman father-in-law Milo de Cogan in the 13th Century. Much later, the old (James) and new (Charles) Forts were constructed to defend Kinsale harbor.

Here is a Google Maps screen capture showing the relationship of our position (the unnamed red drop-pin) on the right, Charles and James Forts and the de Courcy family parklands, the large blank area below the pin named “Dock beach.”

Here are the views looking toward the Celtic Sea, the Old Head of Kinsale and the cliffs at our feet.

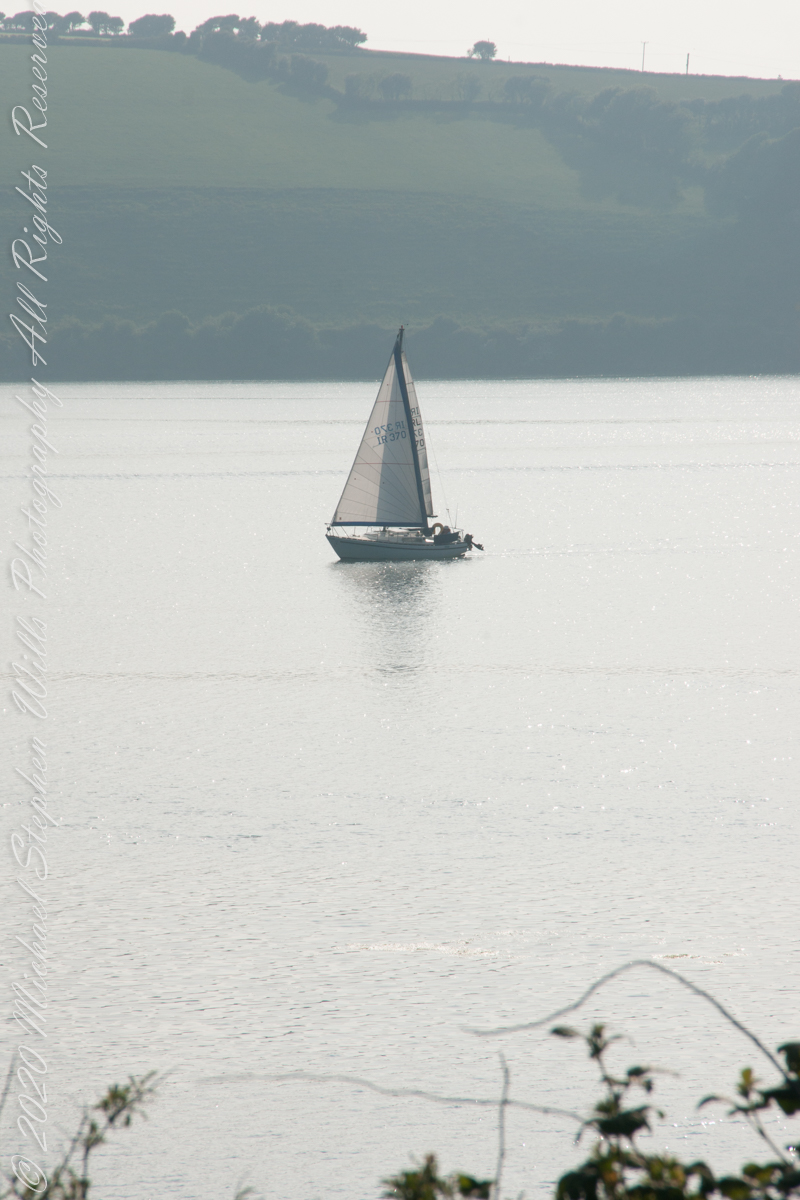

Looking Around

As Pam and I continued down the half mile “Sallyport” footpath, marked in red on the Google Earth view provided at the end of this post, we enjoyed the view across the Celtic Sea toward the distant Old Head of Kinsale and this sailboat headed to port.

Landward, we enjoyed watching the progress of a farmer rolling hay bales while cows munched fresh green grass.

Dún Chathail

A “dun” is a larger fortification, few and far between on the island of Ireland. We saw one on the Arran Islands, from the Iron Age, Dun Angus, Charles Fort, or Dún Chathail in Irish, is from historical ages.

A cannot tell from my slide show, but the walls are star shaped with many salients, giving more positions to defend the walls.

“Charles Fort” – wikipedia

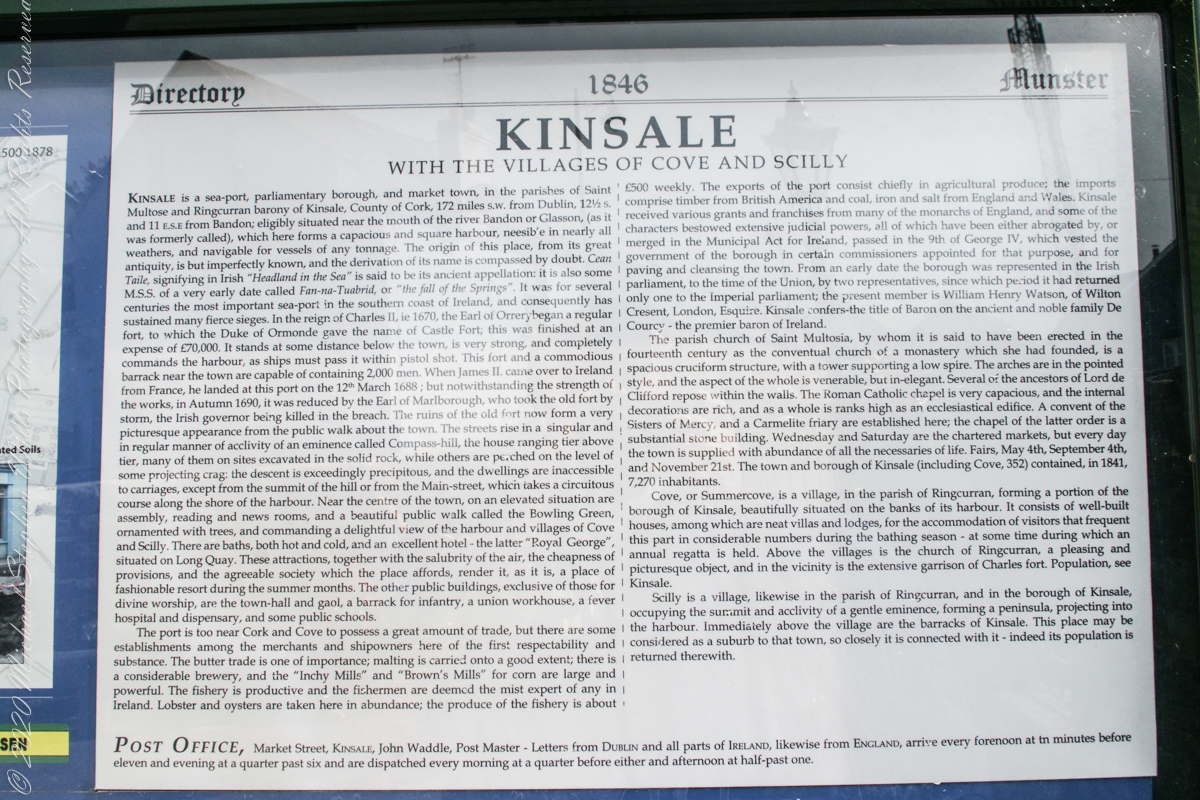

Kinsale, a historic seaport in County Cork, showcases unique architecture and geography, with its streets and houses built on steep inclines near the river Bandon.

The first of a series of idiosyncratic posts from a 2014 walking tour of Kinsale.

Text from an poster behind glass accessible to all and sundry. Directory 1846 Munster, Kinsale with the villages of Cove and Scilly. Kinsale is a seaport, parliamentary borough and market town in the parishes of Saint Multose and Ringcurran barony of Kinsale, County of Cork, 172 miles s.w. from Dublin, 121/2 s and 11 e.s.e. from Bandon; eligibly situated near the mouth of the river Bandon or Glasson, (as it was formerly called), which here forms a capacious and square harbor, accessible in nearly all weathers, and navigable for vessels of any tonnage. the origin of this place, from its great antiquity, is but imperfectly known, and the derivation of its name is compassed by doubt. Cean Taile (Cionn tSáile), signifying in Irish “Headland in the Sea” is said to be its ancient appellation. (see more in the photograph).

Here we are on Emmet Place. There is a row of houses built along a steep alley named “The Stoney Steps.” At top is the aptly named Higher O’Connell Street.

From the informative poster…The streets rise in a singular and in regular manner of acclivity of an eminence called Compass Hill, the house ranging tier above tier, many of them on sites excavated in the solid rock, while other are perched on the level of some projecting crag: the descent is exceedingly precipitous, and the dwelling are inaccessible to carriages, except from the summit of the hill or from Main street, which takes a circuitous course along the shore of the harbor.

Rescue operations and memorials

Our day of touring Kinsale and environs, the last day of May 2014, continues with our morning visit to the “Old Head of Kinsale.” Head is short for headland, a narrow strip of land projecting into the sea.

On May 7th, 1915 the Cunard liner Lusitania was torpedoed 16 km (10 miles) off the Old Head of Kinsale, 40 km (25 miles) west of Queenstown. Of the 1,959 people on board, 1,198 died. Those who survived were brought to Queenstown and Kinsale by rescue vessels and cared for in local hotels and hospitals. Many of those who died were buried at Old Church cemetery, 3 km (2 miles) north of Queenstown. The first class Queen’s Hotel cared for some of the survivors. The elegant Edwardian atmosphere of the hotel was shattered by the horrific news of the loss of the ship. This is the setting for the story of Queenstown’s role in the Lusitania disaster. –text from Cobh Heritage Center poster, see image below.

The Old Head is notable, in the contest of the Lusitania attack, for being the land closest to the incident. Cobh, then named “Queenstown”, was the focus of rescue operations. See text below, from a display of the Cobh Heritage Museum.

The Kinsale tower is just over nine meters high, with walls up to 80 cm thick. Records show a signal crew was in place in 1804 and the tower finished the following year, though severely affected by dampness. When Napoleon was defeated by Wellingtons forces at Waterloo, 1815. With the diminished threat these expensive installations were neglected. The 1899 Ordnance Survey map lists the site as being in ruins. During our 2014 visit the local community was renovating the tower and the work appears complete sometime before 2021.

I did not see and/or recall much emphasis in the museum for pillorying Germany, after all a German U-boat was responsible. Curious, I did a Wikipedia search and found this text. The topic of Ireland, Germany and World War I is complicated.

The original memorial to the Lusitania was unveiled on the 80th anniversary of the May 7th, 1915 sinking (May 7, 1995), Old Head of Kinsale, County Cork Ireland. The imemorial nscription reads “In memory of the 1198 civilian lives lost on the Lusitania 7th May 1915 off the Old Head of Kinsale.”

The inscription of the commemoration plaque accompanying the memorial reads, “This memorial was unveiled by Hugh Coveney D Minister of Defense and The Marine on 7 May 1995.” Around the edge of the medallion reads, “Brian Little Sculptor” “This (cannot read) donated by Lan and Mary Buckley”

19th Century Technology

Our day of touring Kinsale and environs, the last day of May 2014, began with this elegant breakfast by Marantha House near Blarney, our base for County Cork.

On the way to the Old Head of Kinsale. Located in Knocknacurra on the Kinsale side of Bridge Kinsale on R600. Looking toward the peninsula of Castle Park Village and James Fort. Coordinates 51°41’40.1″N 8°31’42.0″W

This tower, at the apex of the Old Head ring route, has extensive views. The next station at Seven Heads, to the southwest, is visible against the skyline on a clear day. These are two of the 81 stations planned for this signaling system implemented in the first years of the 19th century when a French naval invasion was a possibility.

The Kinsale tower is just over nine meters high, with walls up to 80 cm thick. Records show a signal crew was in place in 1804 and the tower finished the following year, though severely affected by dampness. When Napoleon was defeated by Wellingtons forces at Waterloo, 1815. With the diminished threat these expensive installations were neglected. The 1899 Ordnance Survey map lists the site as being in ruins. During our 2014 visit the local community was renovating the tower and the work appears complete sometime before 2021.

during the Great HUNGER, from the Cobh Heritage Center

“Grosse Isle quarantine station was on an island near Quebec in what is now Canada. It was one of the principal arrival ports for emigrants.

Emigration peaked in 1847 when nearly 100,000 Irish landed at Grosse Isle, straining the resources to breaking poinit. Severe overcrowding and an outbreak of typhus caused enormous suffering the the result was a large number of deaths amongst both immigrants and doctors.

New stricter laws were passed to encure that the catastrophe of 1847 was not repeated. Irish emigrant traffic increasingly flowed towards the United State inthe post-Famine period”. From the exhibit (below), Cobh Heritage Center.

In that horrible year of 1847, strict quarantine could not be enforced and many passengers, some carrying disease, were taken directly to Montreal or Quebec city. At least 5,000 died on Grosse Isle in 1847 and thousands more in Quebec, Montreal and during the voyage across the Atlantic.

The unprecedented crisis made it difficult for accurate records to be kept. Some lists were compiled giving details of the possessions of those who died. These lists make sombre reading as they describe the personal belongings of Irish men and women whose hopes of a new life in North America were never fulfilled.

The objects in this showcase provide an representation of the possessions of famine emigrants. From the exhibit (below), Cobh Heritage Center.

Copyright 2021 Michael Stephen Wills All Rights Reserved

during the Great HUNGER, from the Cobh Heritage Center

“The U.S.S Jamestown was the first ship to bring famine relief supplies to Ireland in 1847. Other vessels followed, notably the Macedonian which arrived in Cork July 1847. Captained by George C. DeKay of New Jersey, it carried supplies provided by the citizens of New York, Boston, Main and other parts of the United States. Captain DeKay was warmly welcomed in Cord and special events were held in his honor. Most of the cargo was distributed in Ireland, with some being brought to Scotland to relieve distress there. Other smaller supplies of famine relief goods were sent to Cork from the United States. In April the bark Tartar sailed to Cork with in late June the Reliance left Boston, also destined for Cork. Each carried nearly $30,000 worth of goods for famine relief. From the exhibit (below), Cobh Heritage Center.

United States frigate Constellation with relief stores for Irish distress off Haulbownline in Cork Harbor.

Copyright 2021 Michael Stephen Wills All Rights Reserved