On the underside of a milkweed leaf, the world begins small enough to miss unless you kneel and look closely. In this first photograph the newborn is still a whisper of life, a pale pinhead egg collapsed into a glistening scrap, the tiny caterpillar beside it like a gray comma punctuating the green. It has just eaten the soft shell that cradled it—its first meal, its first thrift. The leaf’s pale roads of veins radiate around the hatchling; within that simple map lies all the geography it needs.

By the second photograph appetite has taken its proper throne. These pilgrims wear a uniform of warning: bands of yellow, black, and white—stripes as bright as hazard tape, a heraldic banner advertising the bitterness borrowed from milkweed. Each bite draws down defensive latex; yet the caterpillars feed undeterred, pausing to snip the leaf’s veins to quiet the flow. Their black, threadlike “tentacles” nod as they travel, and their peppery pellets—frass—collect like midnight hail. Five times they will outgrow themselves, shrugging off skins to reveal wider, hungrier versions within. The room is strewn with green rib and ragged edges; the air has the gentle smell of cut stems. All the while, milkweed’s poisons, the cardenolides, pass into growing bodies and become their bodyguard.

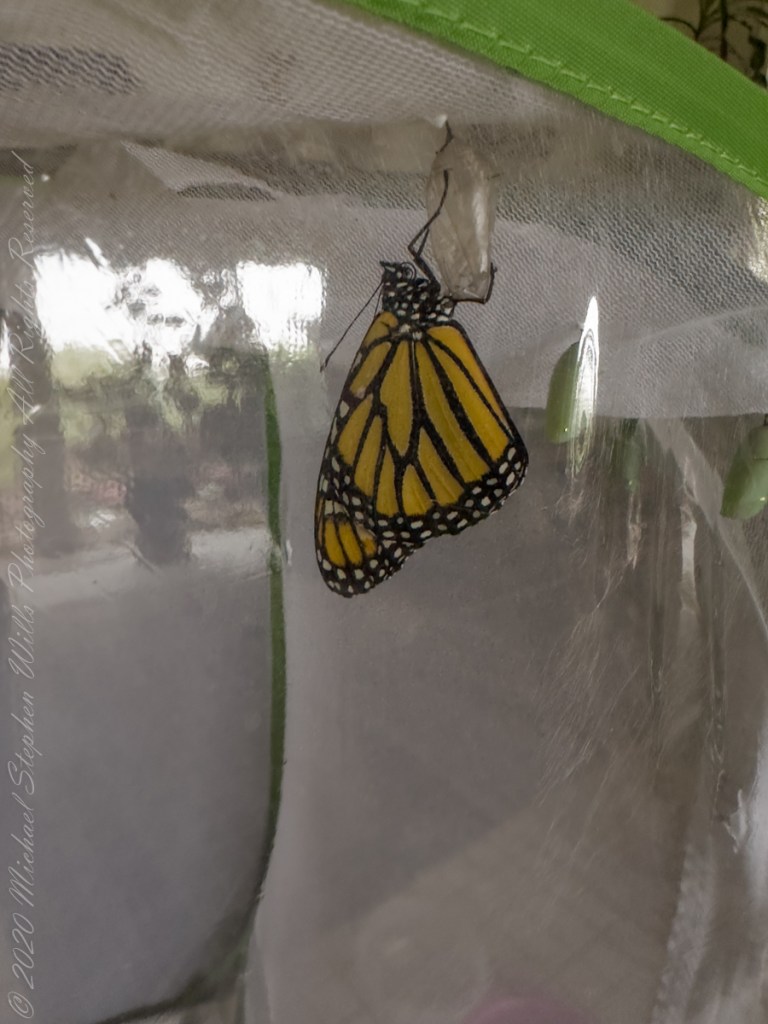

At last a hush. A final meal, a purposeful wander. The caterpillar chooses a high eave of the world—a stem, a stick, the corner of your rearing tent—and hooks itself into a downward J. Within hours the skin splits like a soft zipper; the striped creature pours itself out of itself and seals into a smooth chrysalis.

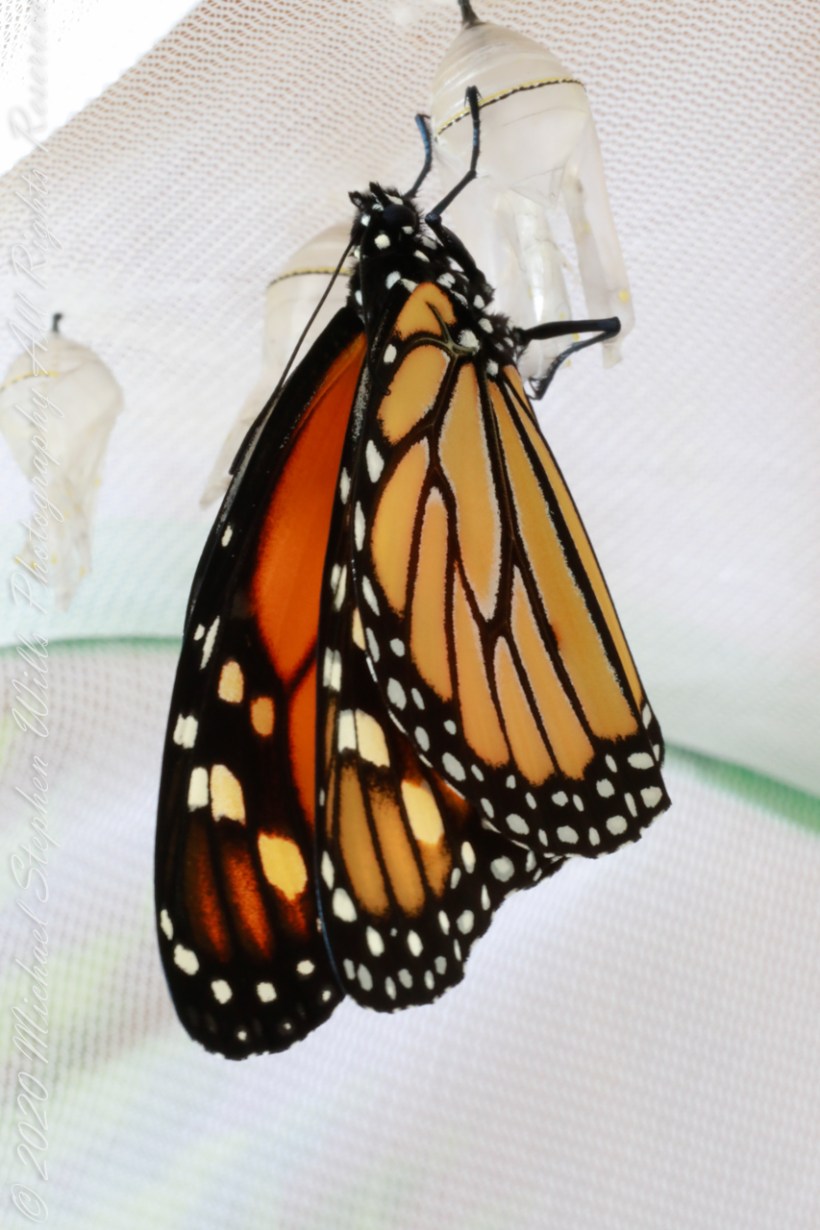

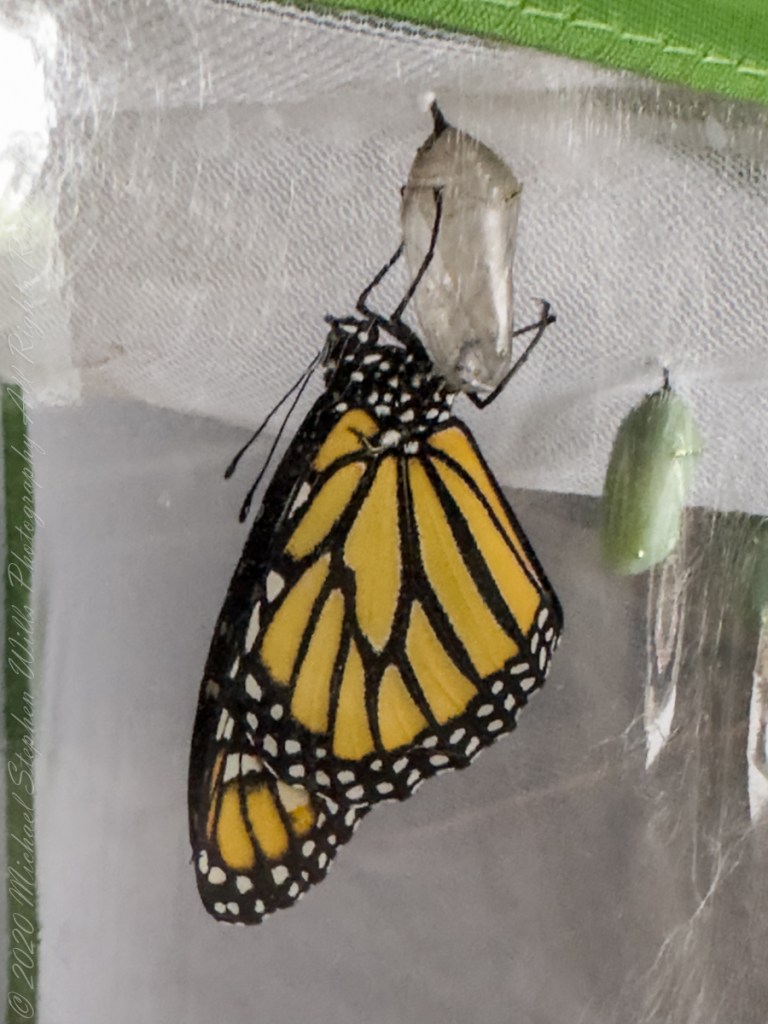

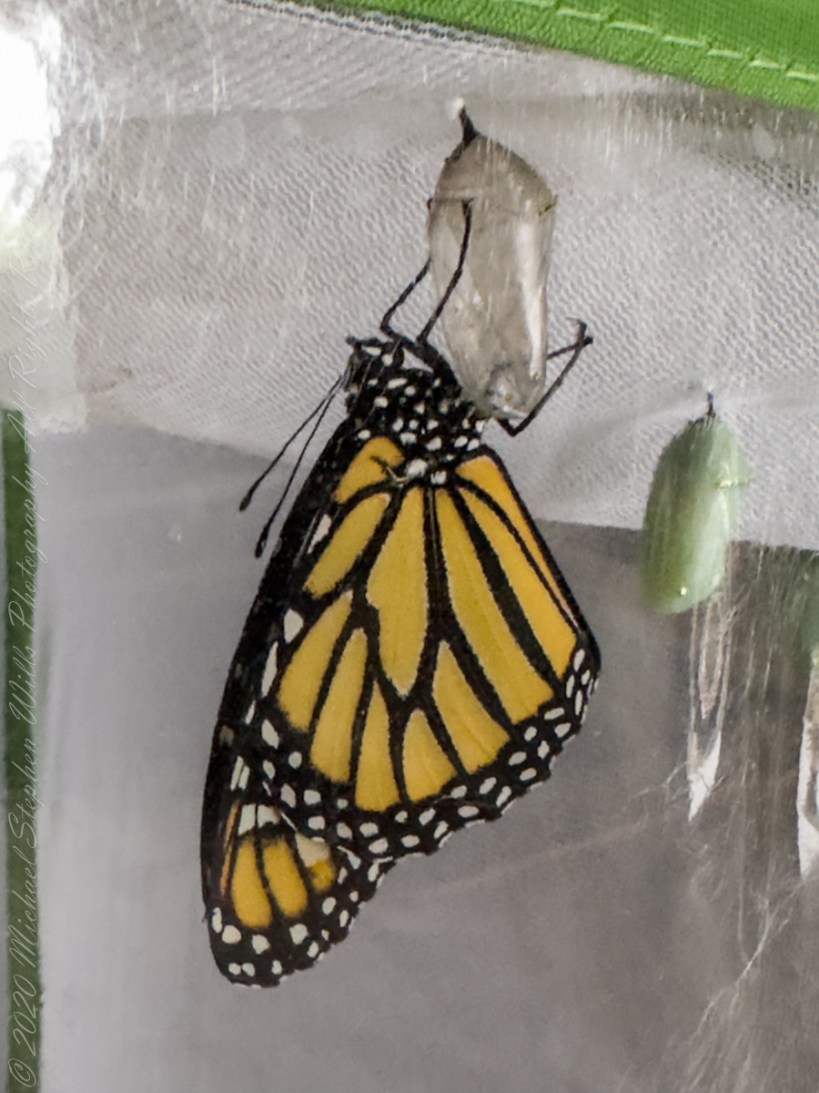

The following photograph and video catch the moments into becoming: the jade lantern has become transparent, darkening, its gold studs glinting like constellation points, and through the thinning walls the folded wings show, orange smoldering under smoke. Inside, old tissues have dissolved into a living broth; imaginal discs—tiny blueprints carried since the egg—have flowered into legs, eyes, and flight. To call it “metamorphosis” is correct; to call it mystery is truer.

Watch on YouTube for a better experience. Please “like” and “subscribe”

When the case opens the butterfly backs into the bright. It clings while the crumpled wings fill and flatten, hemolymph pumping life into every cell. In the next image the adult drinks from a petunia trumpet, a jeweled ember with white-spotted hems. The monarch—Danaus plexippus—tests the wind with new, purposeful wings. Its scientific name nods to ancient stories: Danaus after the Greek mythic king of Argos, a father who fled with his fifty daughters across the sea; plexippus for Plexippus, a figure of the same old tales—his name carried forward into this wanderer of the sky. The English name “monarch” is said to honor both its regal size and domain, and, some say, the orange-and-black of William of Orange. Kings and myths gathered like cloak and scepter around a creature that weighs less than a paperclip.

No butterfly has entered human life more completely. Schoolchildren cradle jars of milkweed sprigs and tape handwritten labels to chrysalides lined like seed pearls along a classroom window. Taggers kneel in September light, add a tiny disc to a wing, and write down time and place so the journey south can be traced. In the mountains of Mexico, where oyamel firs hold winter like a secret, people fold the monarch’s return into the Days of the Dead, believing that souls ride home on those wafers of flame. Gardeners tuck swamp milkweed into narrow beds and call their yards “waystations.” Photographers, such as myself, record the stories that happen leaf by leaf.

Yet our touch is not simple. Fields simplified by herbicides have shaved milkweed from fencerows; tidy mowing removes nectar from roadsides in the tender weeks of migration; captive rearing in vast numbers, though done with reverence, may carry unintended risks of disease and weakened orientation. The monarch asks us to enlarge our sense of home beyond the fence: to let patches of milkweed lift their pale crowns in rough corners; to choose late-blooming asters and goldenrod; to keep a few ditches shaggy until the travelers pass. Conservation, like metamorphosis, is work that happens inside ordinary days.

Watch the cycle again in my images—egg to appetite, appetite to stillness, stillness to wing—and hear what it whispers in the steady voice of milkweed leaves and soft fall air. Rachel Carson wrote that “those who contemplate the beauty of the earth find reserves of strength that will endure as long as life lasts.” Here beauty wears stripes and beads of gold, sips from garden petals, and threads a continent with its frail insistence. The monarch’s life is a ribbon we can follow with our eyes and, if we are willing, with our hands—gentle hands that leave room for milkweed to rise, for caterpillars to feed, for a chrysalis to darken and a window to fill, one bright morning, with wings.

On a personal note, this season was a success. Monarchs visited our milkweed patch several times allowing me to save/harvest nineteen eggs/caterpillars and raise them until release.

Selected references

Carson, Rachel. The Sense of Wonder. New York: Harper & Row, 1965. (Reissued: HarperCollins, 1998; Open Road Media e-book, 2011.) The quoted passage (“Those who contemplate the beauty of the earth…”) appears early in the book; the Open Road edition places it on p. 41.

Wikipedia contributors. “Monarch butterfly — Etymology and taxonomy.” (useful overview with primary citations).

Oberhauser, K. S., and M. J. Solensky, eds. The Monarch Butterfly: Biology and Conservation. Cornell University Press, 2004.

Enter your email to receive notification of future postings. I will not sell or share your email address.