Arriving at 5 am there is a line of trucks and cars and Piestewa Peak parking almost full when I grab a spot in the predawn darkness. The desert air has that deep, merciful coolness it offers before sunrise, edged with the long-remembered scent of creosote. Car doors close with soft thuds, headlamps blink on, and a loose procession of strangers begins to funnel toward the trailhead like pilgrims, even now white and red headlamps sprinkle the upper slopes.

At first the climb exists only in a narrow cone of light, my lamp illuminates the scant gravel, uneven steps, and each scuff of boot or shoe sounds loud in the hush. Somewhere below, the city hums, but here the conversation is mostly breath and the occasional murmur of greeting as we fall into the rhythm of the climb.

My beam catches a young couple just ahead, their hands knotted together. They speak Spanish, laughing quietly as they miss a step and bump shoulders. Behind me an older man in a Veterans cap leans heavily on trekking poles, his companion—maybe daughter, maybe friend—matching her shorter stride to his with patient care. A group of women in bright leggings and braided hair moves past us in a burst of energy, their languages overlapping—English, maybe Vietnamese, something I cannot place—like the weaving of a rug. A man passes me, a drum on his back. Piestewa draws them all, before dawn, to this rib of stone in the center of the Phoenix basin.

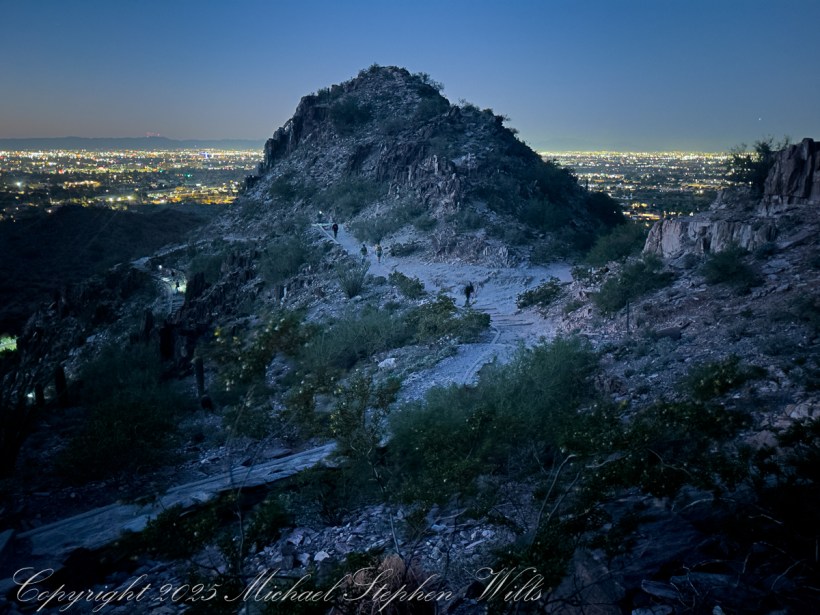

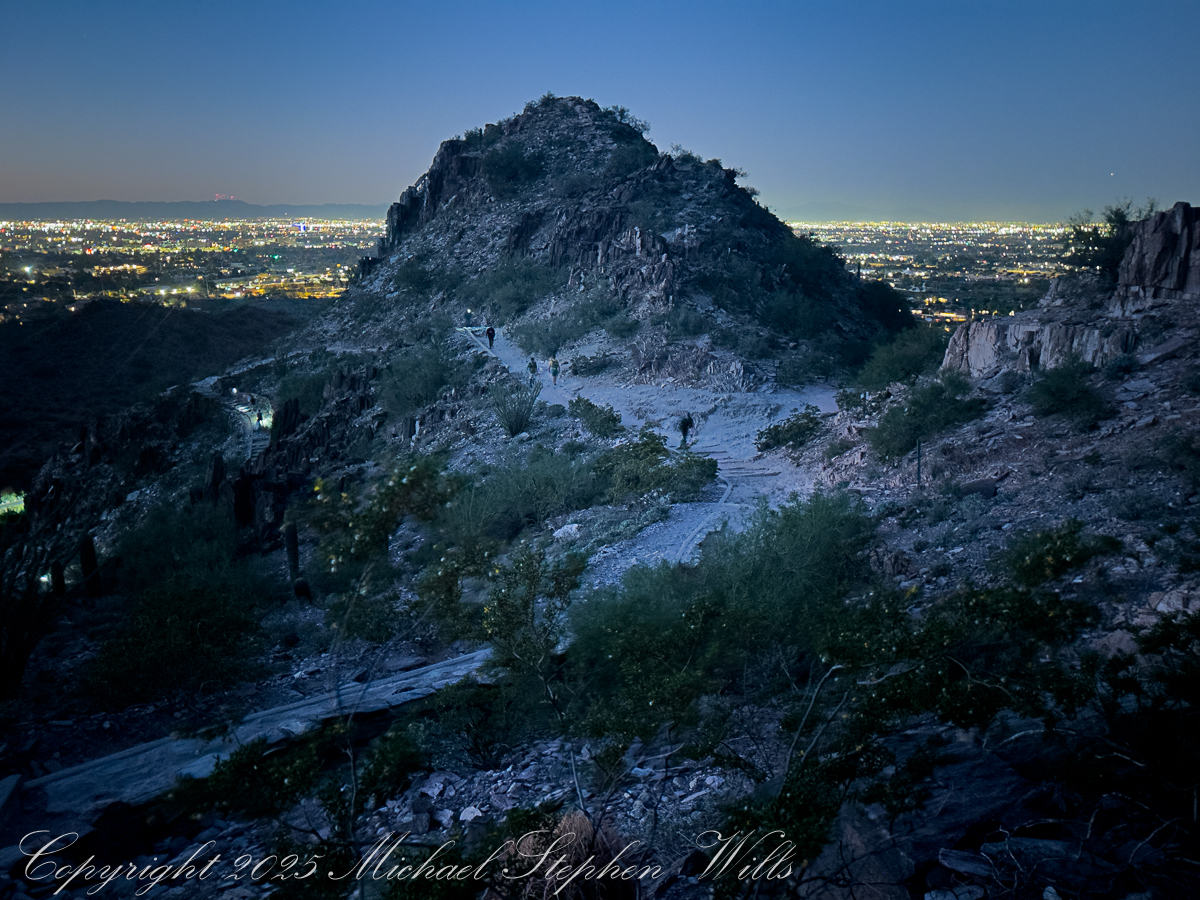

As I stop to rest myself and turn off my headlamp, ahead the trail tilts steeper the steps fade to rock, irregular and unforgiving: a stairway carved from ancient volcanic bones. With my dark adaptation, surfaces reflect star and city light, leading the eye down the ridge toward the dark quilt of neighborhoods below. Later, captured in the photograph, those steps will twist away like a stone dragon’s spine, the city waking beyond in soft pastels. Now they are simply work for legs and lungs.

The desert plants materialize around us as shapes before they acquire color. Saguaros stand like sentinels along the slopes; their arms lifted in silhouette. Ocotillo rise as witchy bundles of sticks, each spine leafed out from October rains the leaves catching a little light. On a small plateau a family has paused; the father adjusts a tiny headlamp on his son, no more than six, who is insisting, with fierce determination, that he can carry his own water. “Almost there, campeón,” his father says, and the child straightens like a soldier.

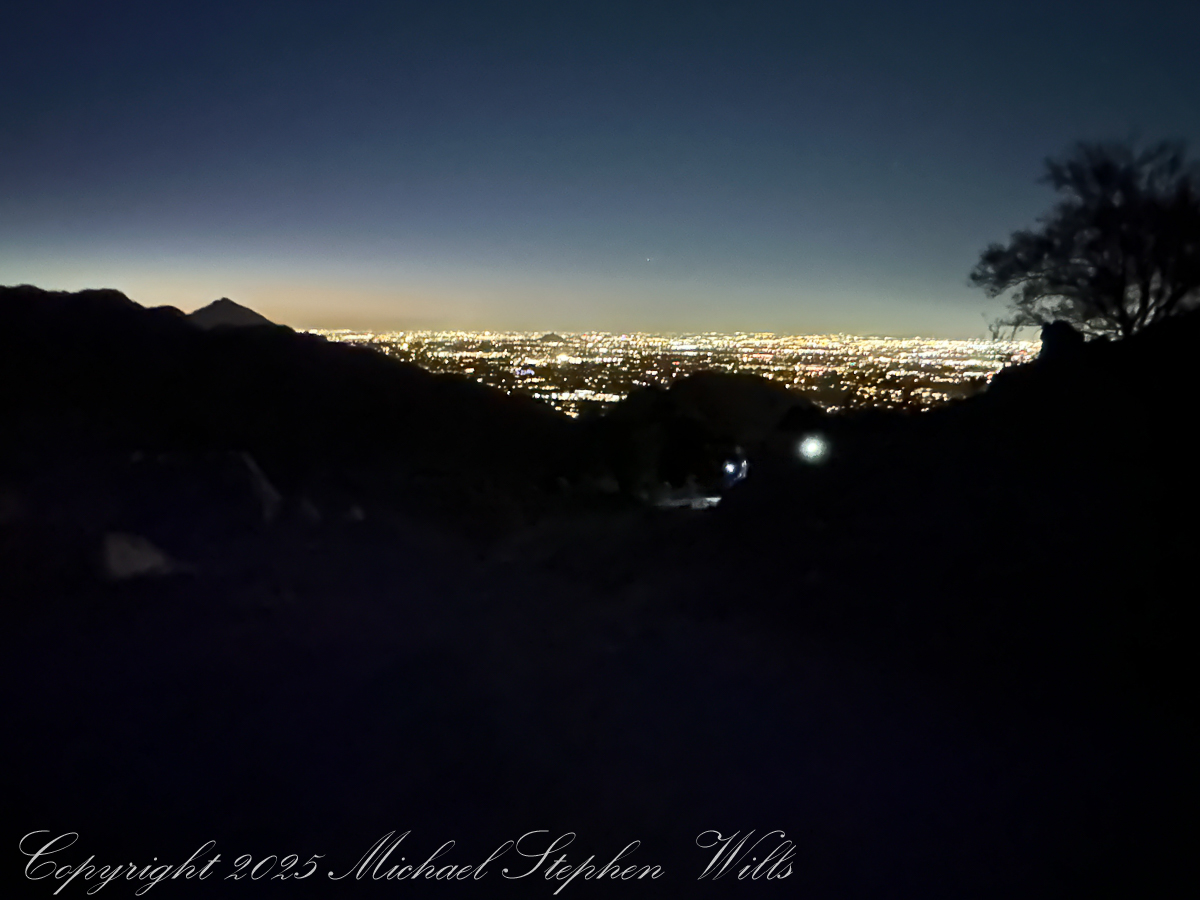

The dark begins to soften at the edges. Over the eastern horizon a thin band of orange appears, a delicate seam between night and day. In one direction, the city stretches out in a glittering net of streetlights, the squares of parking lots and subdivisions catching the last of the darkness. In the other, the mountains are still black cutouts, their profiles sharp as paper against a gradually brightening sky. One of my images will hold that moment: the jagged ridge of Piestewa in shadow, the valley below already spangled with light, a single towering saguaro rooted at the cliff’s edge like a punctuation mark.

Higher up, the trail narrows and the rock turns rougher. We fall into single file, strangers linked by a line of effort. A runner comes flying down, feet barely touching stone, breath steady and controlled. “On your left,” he calls, and we part for him like water. A woman with a hijab tucked neatly under her ball cap leans against the retaining wall, stretching a calf muscle, her friend counting in accented English: “Ten more seconds, you can do it.” Near one bend a hiker pauses to press a hand against the rock face, whispering a quiet prayer in a language I do not recognize. It is a small, intimate moment, gone almost before I register it.

The last push to the saddle is steep, the steps uneven, the sky now a cascade of colors—copper, rose, faint lavender melting into a high dome of blue. The silhouettes of distant ranges sharpen: the Estrellas?, the Superstitions?, low ridges whose names I do not know. On the horizon, the first thin line of sun breaks free, setting fire to the edges of clouds. In another photograph, framed by dark rock and desert trees, that sunrise becomes a golden portal at the end of a shadowed corridor of stone.

We reach a broad ledge just shy of the summit as the light finally spills over us. People are already gathered there: a trio of college students taking selfies, a pair of retirees sharing thermos coffee, a solitary man sitting cross-legged with eyes closed, face open to the warmth. The city below is suddenly transformed. The carpet of lights dims, replaced by the clear geometry of streets and rooftops, golf courses and parking lots, all laid out like a model at our feet. The mountains that hem the basin—once anonymous shapes—now reveal their ridges and ravines in sharp relief.

For a few minutes conversation dies away. Everyone seems to feel the same thing: that fragile instant when the sun clears the horizon and the desert shifts from silver-blue to gold. The rocks around us, sharp and broken in the photographs, glow honey-colored. Saguaros catch light on their spines, each thorn a tiny ember. Even the dusty air seems to shimmer.

Down below, a new wave of hikers starts up the trail, latecomers walking into full daylight. We, the predawn climbers, share a small, quiet complicity. We have seen the city from the backside of night, watched the day arrive from a perch of jagged stone. Piestewa Peak has turned us, for an hour or two, into a single, breathing organism: many hearts, one climb, all of us stitched together by the steep path and the slow unveiling of the sun.