Arcosanti, the brainchild of architect Paolo Soleri, was conceived as an experimental laboratory for urban design and ecological principles—a built embodiment of his vision of Arcology (a fusion of “architecture” and “ecology”). Over fifty years since its groundbreaking in 1970, Arcosanti remains a significant cultural and architectural artifact. However, the meaning and relevance of both Arcosanti and Arcology in today’s context invite critical examination.

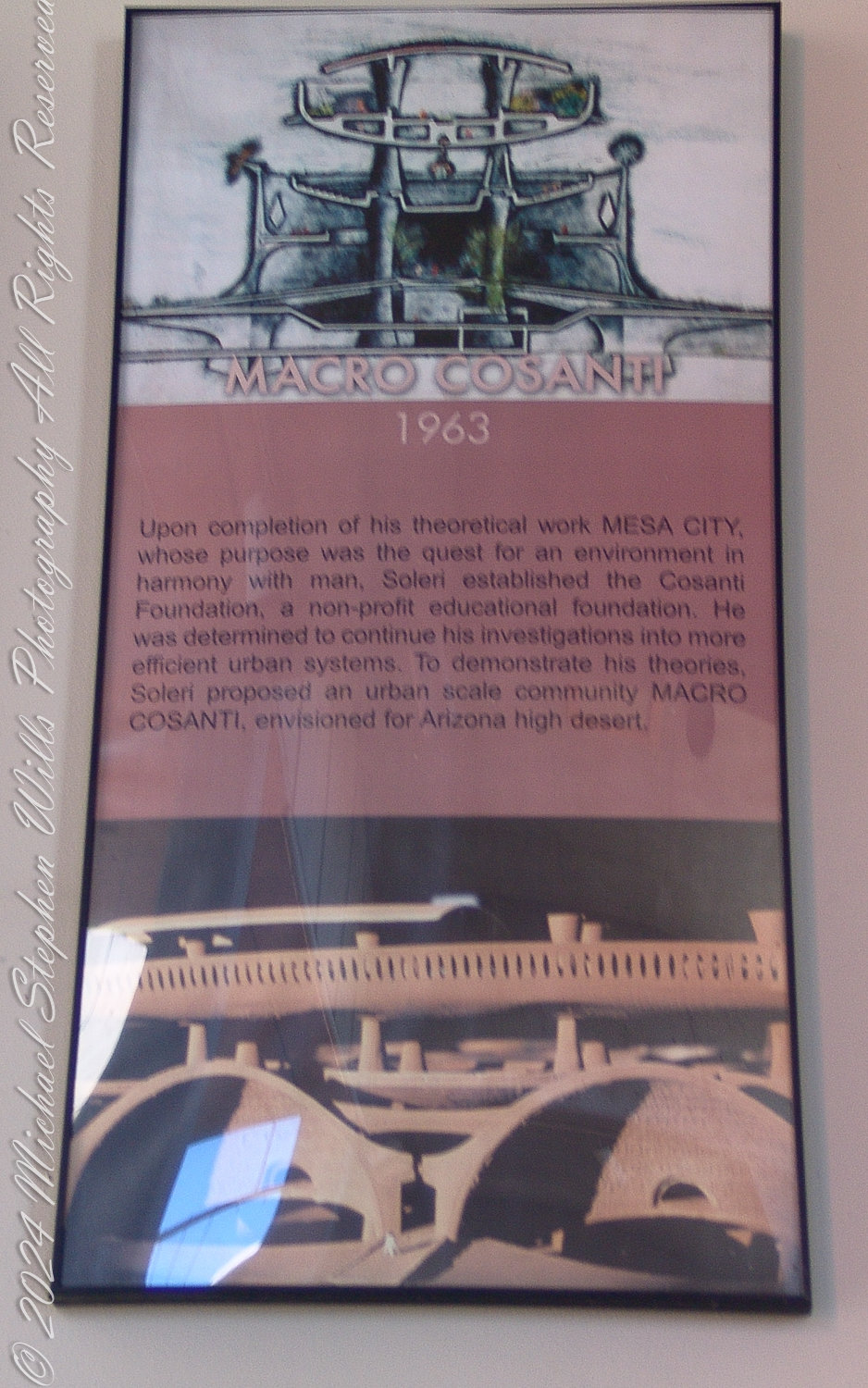

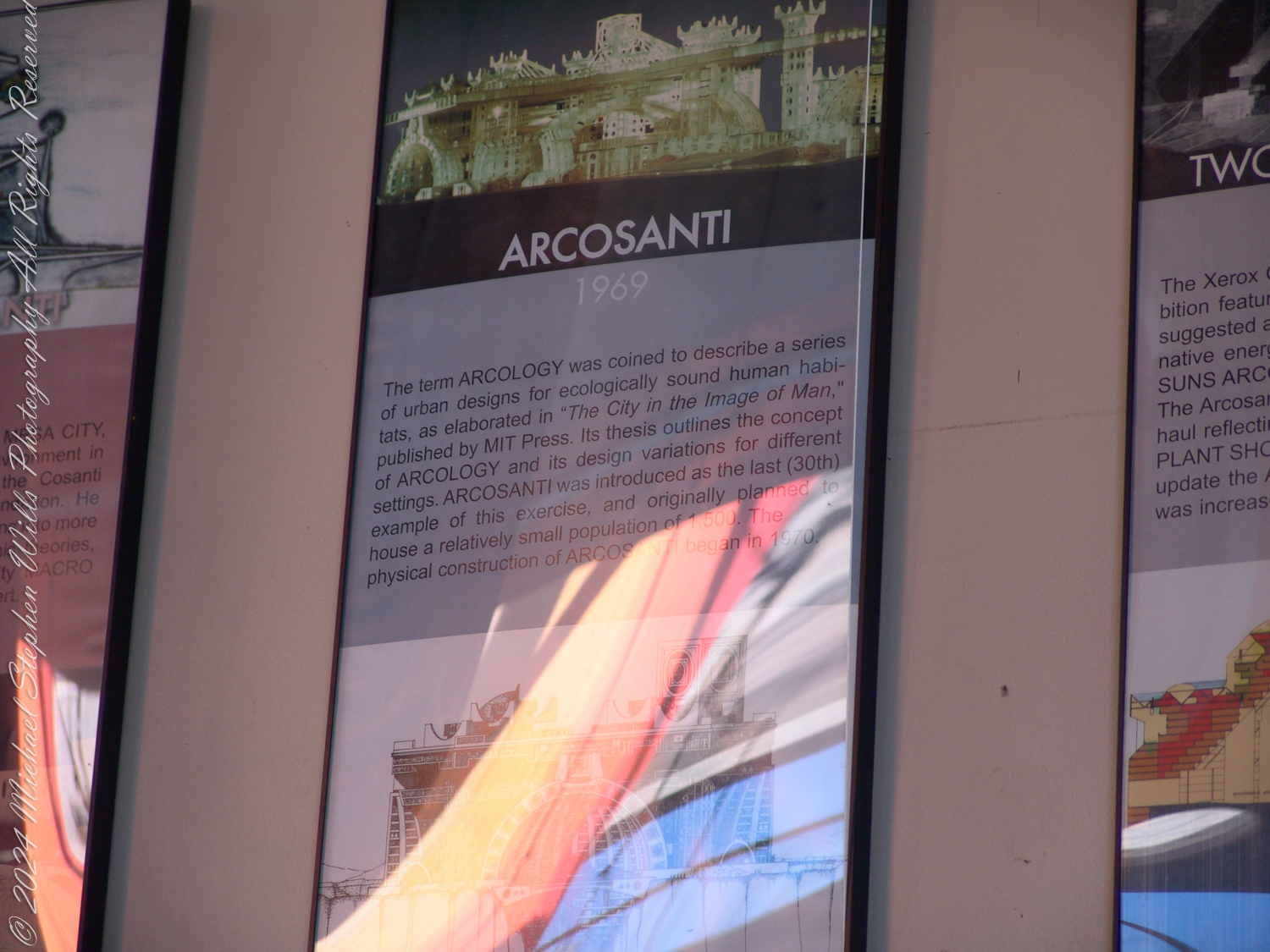

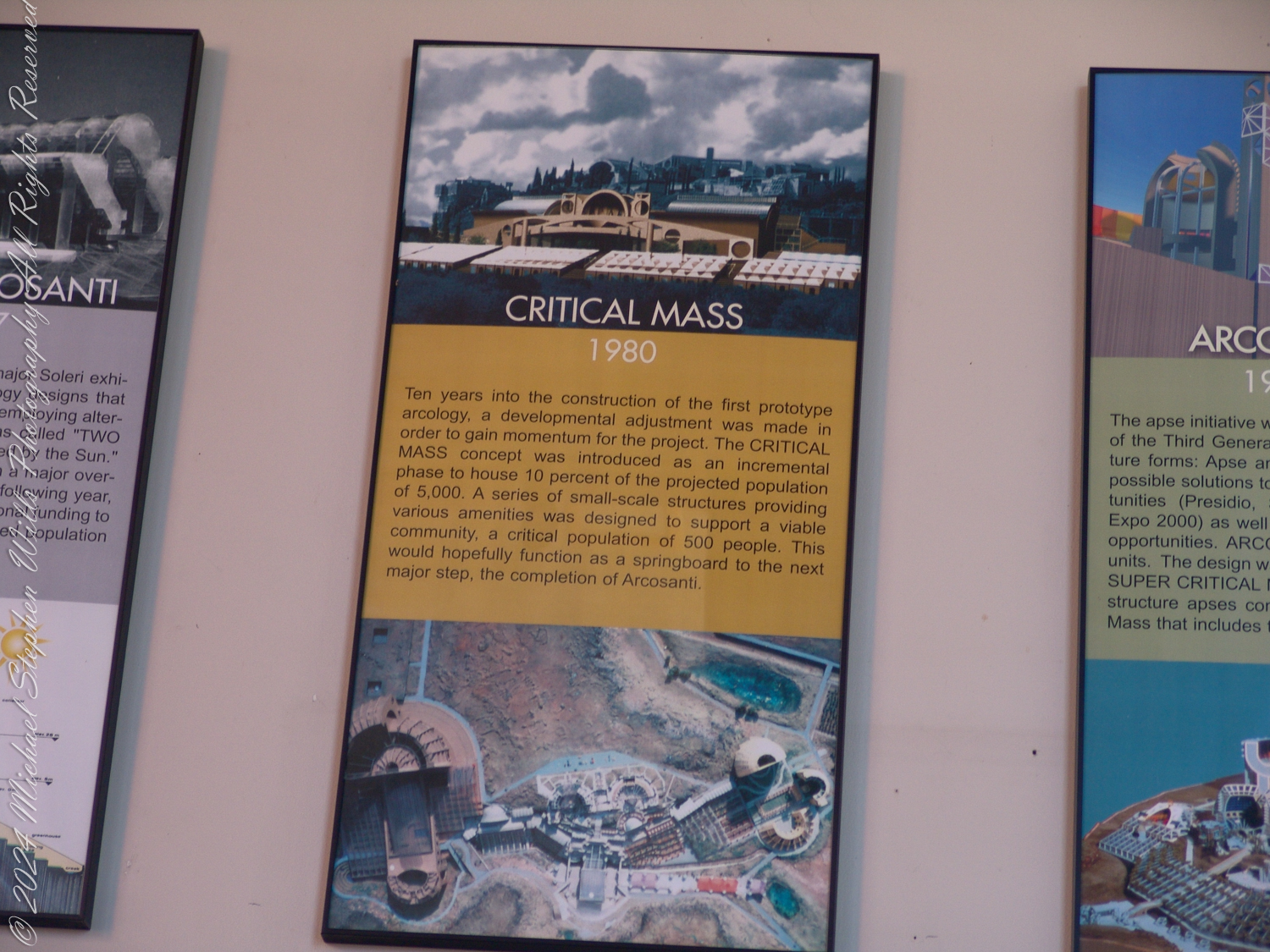

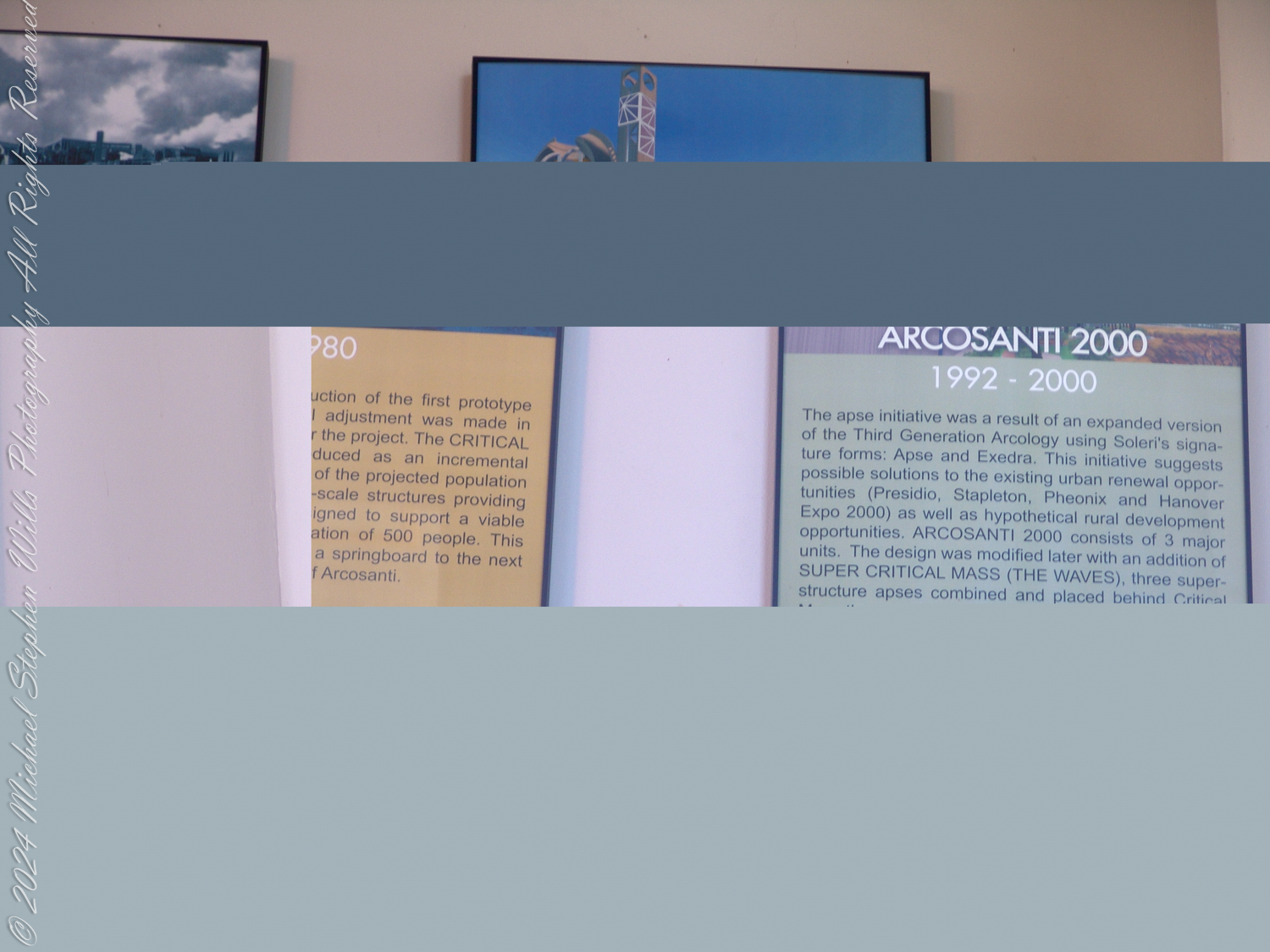

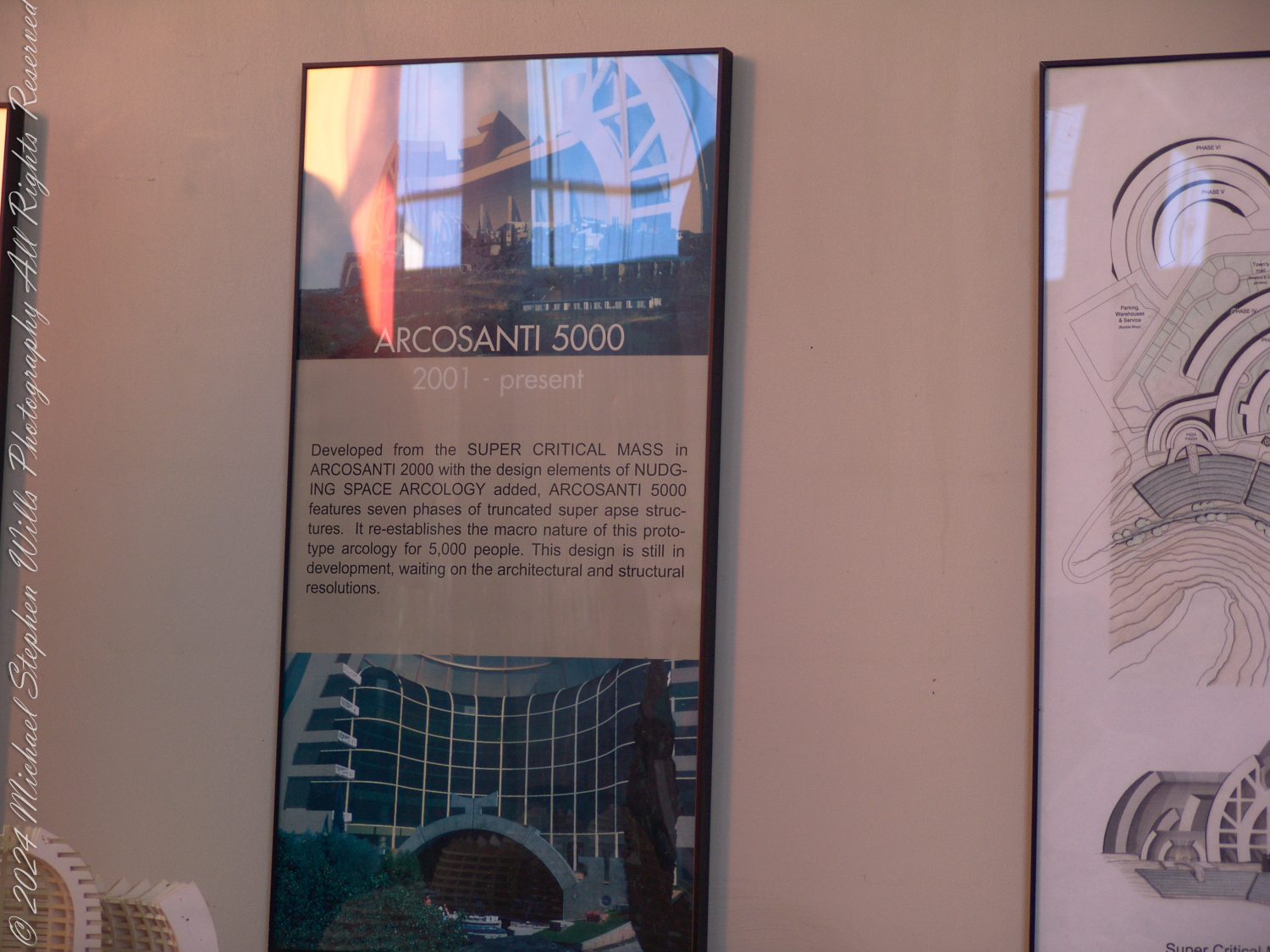

The accompanying photographs are a presentation of the history of Arcology from Arcosanti signage

Historical Context and the Vision of Arcology

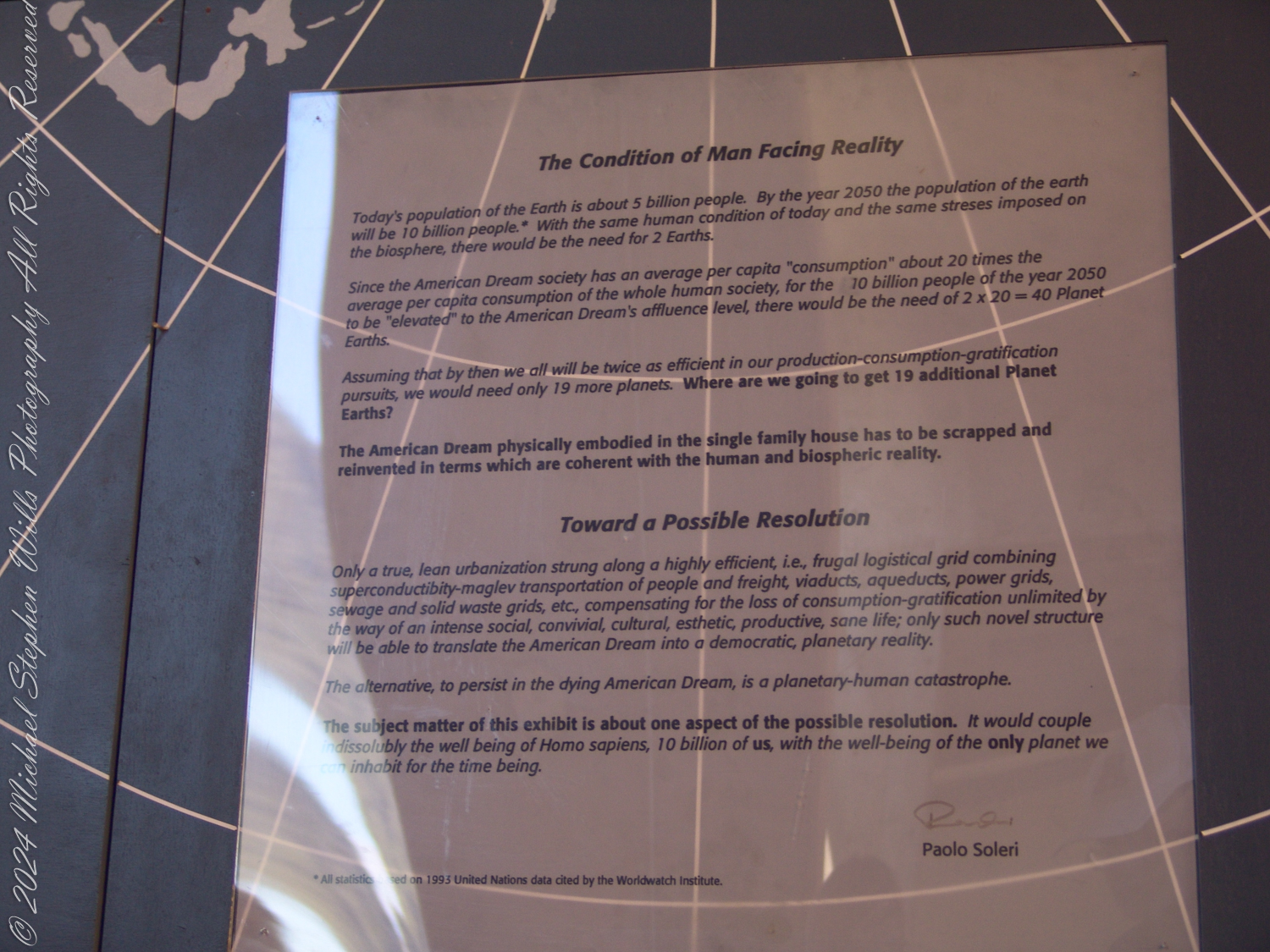

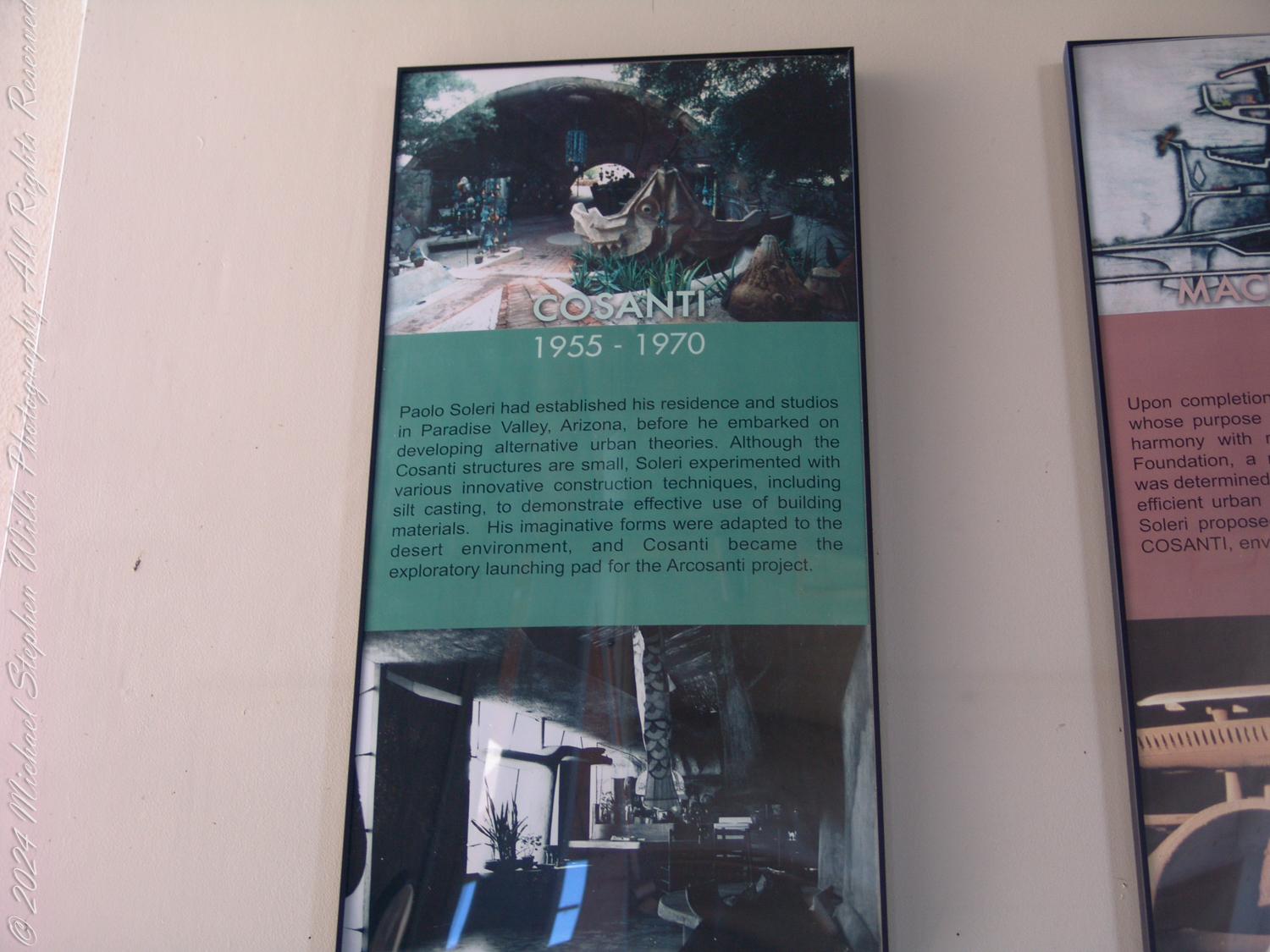

Soleri’s concept of Arcology emerged during the mid-20th century, an era of increasing environmental awareness, urban sprawl, and population growth. His vision was radical: compact, self-sustaining urban environments that minimized ecological impact while fostering human interaction and creativity. Arcology sought to challenge the sprawling, resource-intensive models of urban development that dominate the modern world.

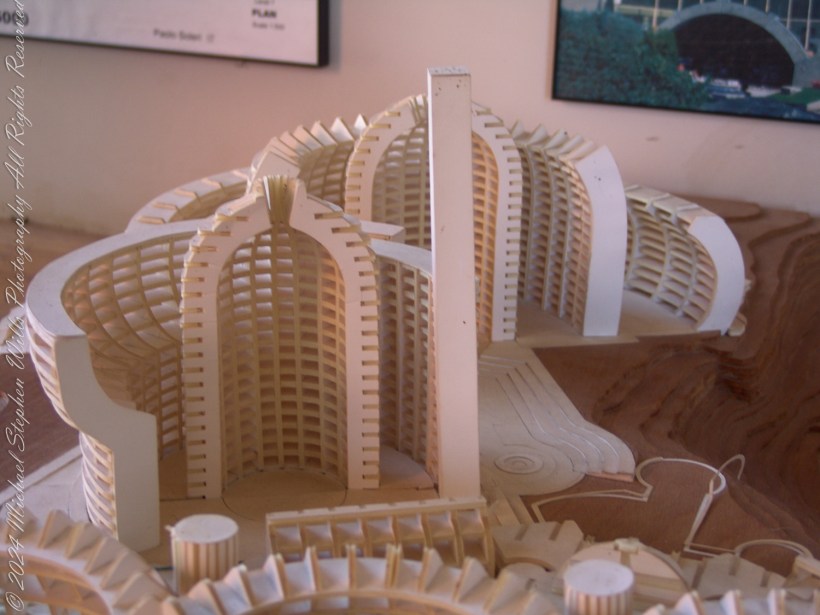

Arcosanti was intended to be a prototype—a proof of concept for dense urban living within a minimal environmental footprint. Its design embraced verticality, integration with natural surroundings, and multi-use spaces to reduce resource consumption. Soleri’s philosophy rejected wasteful consumerism and emphasized communal living, self-sufficiency, and harmony with nature.

Arcosanti as a Realization of Arcology

While Soleri’s ideas were visionary, Arcosanti itself never fully realized its original ambitions. Planned to house 5,000 people, it currently accommodates fewer than 100 residents. This gap between aspiration and reality reflects several challenges:

Scale and Funding: Building a sustainable community of this scale required vast financial and organizational resources. Arcosanti, largely constructed through volunteer labor and workshops, lacked the momentum to expand at the pace Soleri envisioned.

Cultural Shifts: The communal living and austerity championed by Soleri contrast sharply with the consumer-driven values of contemporary society. The rise of globalized capitalism, suburban expansion, and digital individualism has made the communal ethos less appealing to many.

Technological Advances: Soleri’s designs were innovative for their time, but modern advancements in sustainable technology—such as solar power, green building materials, and decentralized energy systems—have surpassed some of his ideas. Today, sustainable urbanism focuses on retrofitting existing cities rather than building entirely new ones.

The Relevance of Arcology Today

Despite its limitations, Arcology remains profoundly relevant in the face of 21st-century challenges such as climate change, resource scarcity, and urban overpopulation. Soleri’s principles offer a framework to address these crises, particularly through:

Compact Urbanism: Cities worldwide are grappling with the environmental toll of urban sprawl. Arcology’s emphasis on vertical, compact cities with reduced land usage aligns with the modern push for urban densification.

Mixed-Use and Communal Spaces: The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the importance of walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods and shared green spaces. Arcology’s model of integrated living and working spaces anticipates these needs.

Sustainability and Circular Systems: Soleri’s focus on minimizing waste and resource use aligns with today’s circular economy principles. Arcology’s ideas resonate with efforts to design cities as closed-loop systems that reuse resources.

A Philosophical Challenge: Beyond practical urban design, Arcology challenges us to rethink our relationship with the planet and with each other. It invites a fundamental shift from individualistic consumption to collective stewardship.

Critique of Arcosanti Today

Arcosanti, while iconic, serves more as a symbol than a fully functioning example of Arcology. Its limited population and incomplete development highlight key shortcomings:

Lack of Scalability: Arcosanti has not demonstrated how Arcology principles can scale to meet the needs of modern cities with millions of inhabitants.

Dependence on External Systems: Despite its aspirations for self-sufficiency, Arcosanti relies on external power grids, supply chains, and tourism, which limits its autonomy.

Cultural Niche: Arcosanti appeals primarily to a niche audience of artists, architects, and environmentalists, making it less accessible or appealing to broader populations.

However, these critiques do not negate its value as a learning tool. Arcosanti’s enduring presence serves as a physical and philosophical case study for those seeking alternatives to conventional urbanism.

A Way Forward?

The future of Arcology lies not in building new Arcosanti-like prototypes but in applying its principles to existing cities and communities. Initiatives such as urban vertical farming, passive solar building design, and car-free city centers echo Soleri’s vision in modern contexts.

Additionally, Arcosanti itself could pivot toward becoming a research hub for sustainable practices, a cultural landmark, or a retreat for those seeking inspiration in Soleri’s ideas. By focusing on education and experimentation, it could remain relevant in contemporary discussions about urbanism and ecology.

Conclusion

Arcosanti and Arcology are more than relics of a bygone architectural movement—they are reminders of humanity’s potential to live in balance with nature. While the practical implementation of Arcology faces significant hurdles, its core philosophy continues to inspire efforts to create more sustainable and harmonious urban environments. In a world increasingly shaped by environmental urgency, Soleri’s vision holds lessons we cannot afford to ignore.