In the heart of upstate New York, the Finger Lakes region stretches out like a handprint left by the last great ice sheets—long, narrow lakes aligned north to south, their steep-sided valleys feeding into a lattice of creeks, waterfalls, and wetlands. It is a landscape defined by water and time: glaciers grinding south, then melting back north some 12,000 years ago, carving deep troughs, piling up ridges of gravel and sand, and leaving behind a terrain that is anything but simple.

The O.D. von Engeln Preserve at Malloryville, near the small village of Freeville, is one of the quiet places where that story is written most clearly on the land. It doesn’t shout like Taughannock Falls or Ithaca’s famous gorges. Instead, it whispers—through the curves of its hills, the softness of its ground, the unexpected appearance of a spring at the base of a gravel ridge. Here, in a relatively compact area, you can see how ice and water worked together to shape the Finger Lakes region we know today.

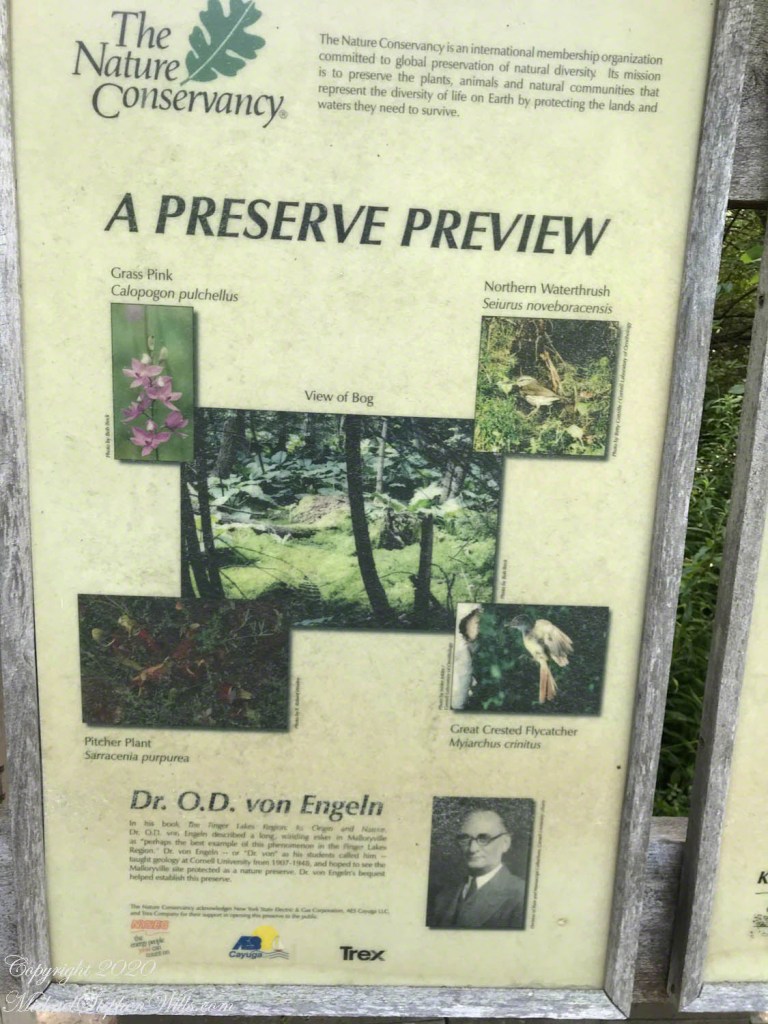

By the time the preserve officially opened in 1997, the name O.D. von Engeln was already familiar to anyone curious about local geology. His classic book on the Finger Lakes helped generations of readers understand that the scenery around them was not random, but the result of powerful, understandable processes. Reading von Engeln, the rolling hills and quiet valleys near Freeville become more than background—they become evidence: of buried ice, rushing meltwater, and the slow settling of sediments into the forms we walk on now.

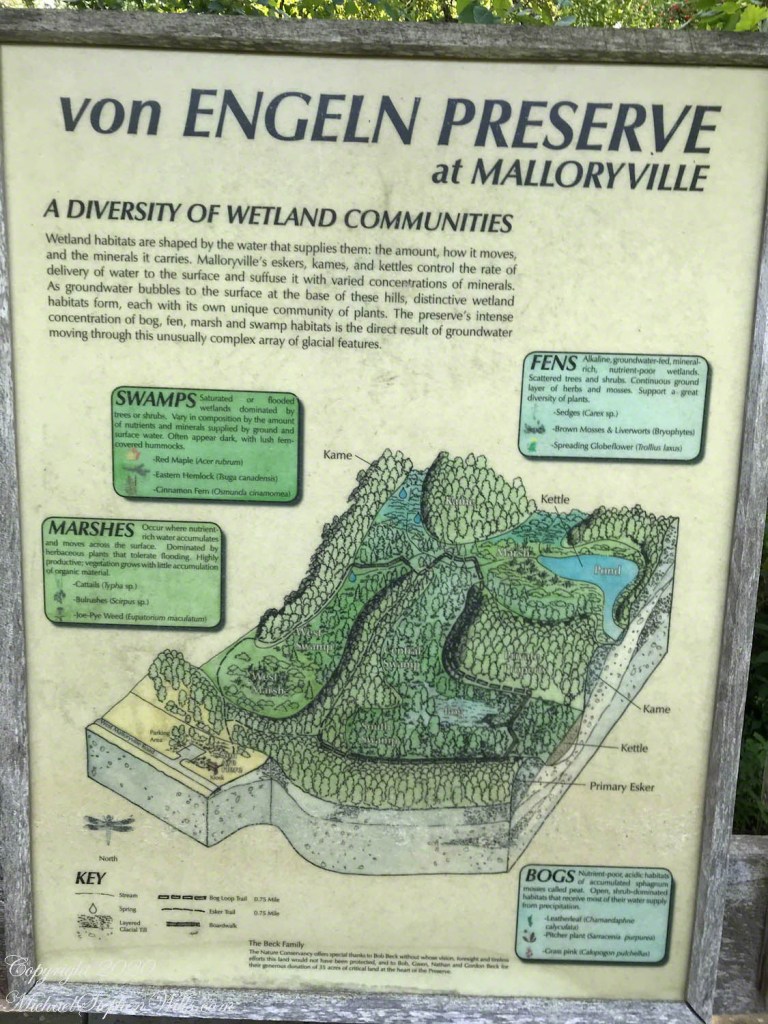

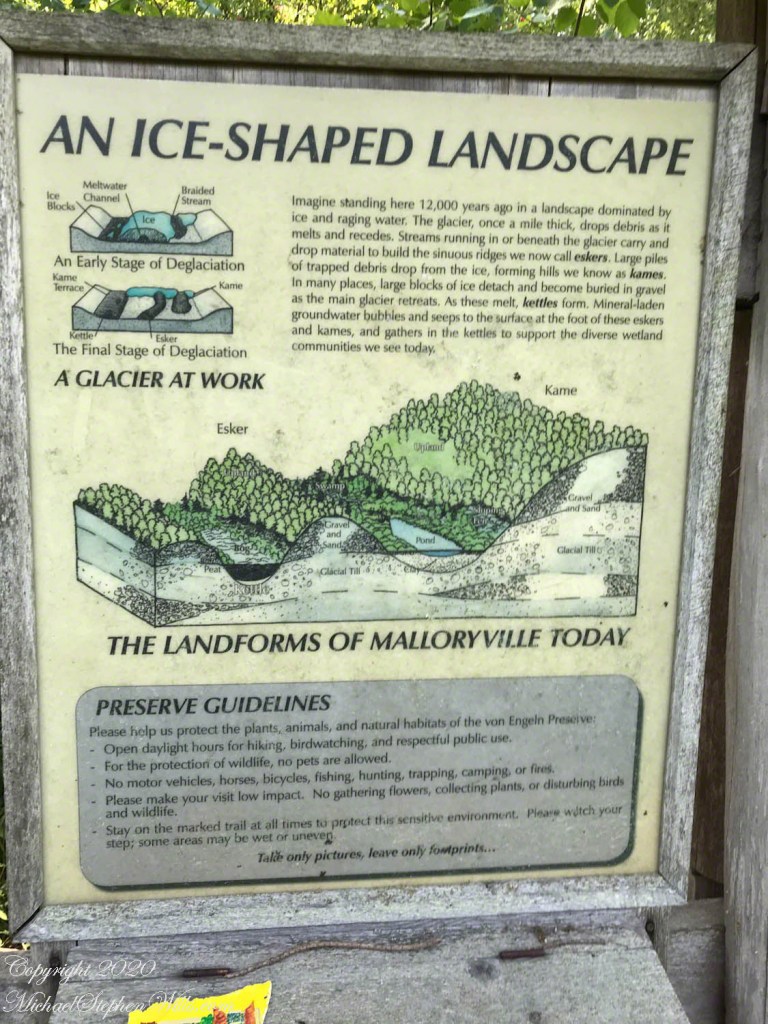

Malloryville is an outdoor classroom for that lesson. The preserve is built around a cluster of glacial landforms—eskers, kames, and kettles—that create a three-dimensional mosaic of ridges and hollows. Eskers, those long, winding gravel ridges left by rivers that once flowed inside the glacier, snake through the forest like frozen currents of stone. Kames—steep, irregular hills of sand and gravel—rise suddenly from the surrounding lowlands. Kettles, the depressions left behind when buried ice blocks melted away, now cradle wetlands and pools.

Beneath and between these features, groundwater is constantly on the move. It seeps through layers of sand and gravel, emerges as cold springs at the foot of slopes, and spreads out into swamps, fens, and marshes. In the Finger Lakes, water is always telling a story; at Malloryville, it’s simply easier to hear. Follow the trail and you move through a succession of wet worlds: a seep-fed fen with delicate mosses and sedges, a shrub swamp where skunk cabbage thrusts up in early spring, a cattail marsh that hums with birds and insects in summer.

For my family, the story of Malloryville began even before the preserve had a name. We lived nearby along Fall Creek, itself a thread in the larger fabric of the Cayuga Lake watershed. My son and I camped for the first time on top of an esker just beyond our front door, our tent perched on what I would later learn was the remnant of a stream that once tunneled through the base of a glacier. At the time, it was simply a magical narrow ridge in the woods. Only later, with von Engeln’s guidance and the preserve’s interpretive signs, did that ridge become a sentence in a much older, longer narrative.

That is one of the great gifts of the Finger Lakes: the chance to move from simple admiration—“this is beautiful”—to understanding—“this is how it came to be.” The steep slopes along Cayuga, Seneca, or Skaneateles; the drumlin fields near the north ends of the lakes; the hanging valleys and waterfalls; and the quiet wetlands of places like Malloryville are all chapters in the same glacial chronicle. Once you learn to read one place, you begin to read them all.

Walking into the O.D. von Engeln Preserve, you enter that story at a small, intimate scale. The parking area and trailhead give way quickly to a world where the ground feels different—sometimes firm and gravelly, sometimes soft and yielding underfoot. Wooden walkways and narrow paths thread through shady forest and open wetland. Each bend offers a subtle shift: a new plant community, a change in water clarity or flow, a small sign explaining what lies beneath your feet.

This is not grand scenery in the postcard sense; it is something quieter and deeper. Malloryville invites you to slow down and notice. To ask why a particular ridge is so narrow, why water emerges here but not there, why one hollow is filled with shrubs and another with moss and sedge. In learning those answers, you gain not only an appreciation for this modest preserve but also a richer understanding of the entire Finger Lakes region.

In the end, the O.D. von Engeln Preserve at Malloryville is a lens—a way of seeing. Through it, the familiar landscapes of central New York—valleys, hills, streams, and lakes—come into sharper focus as the lasting work of ice and water. Stand on an esker, look across a kettle wetland, listen to the quiet trickle of a spring, and you are standing inside the very processes that shaped the Finger Lakes.