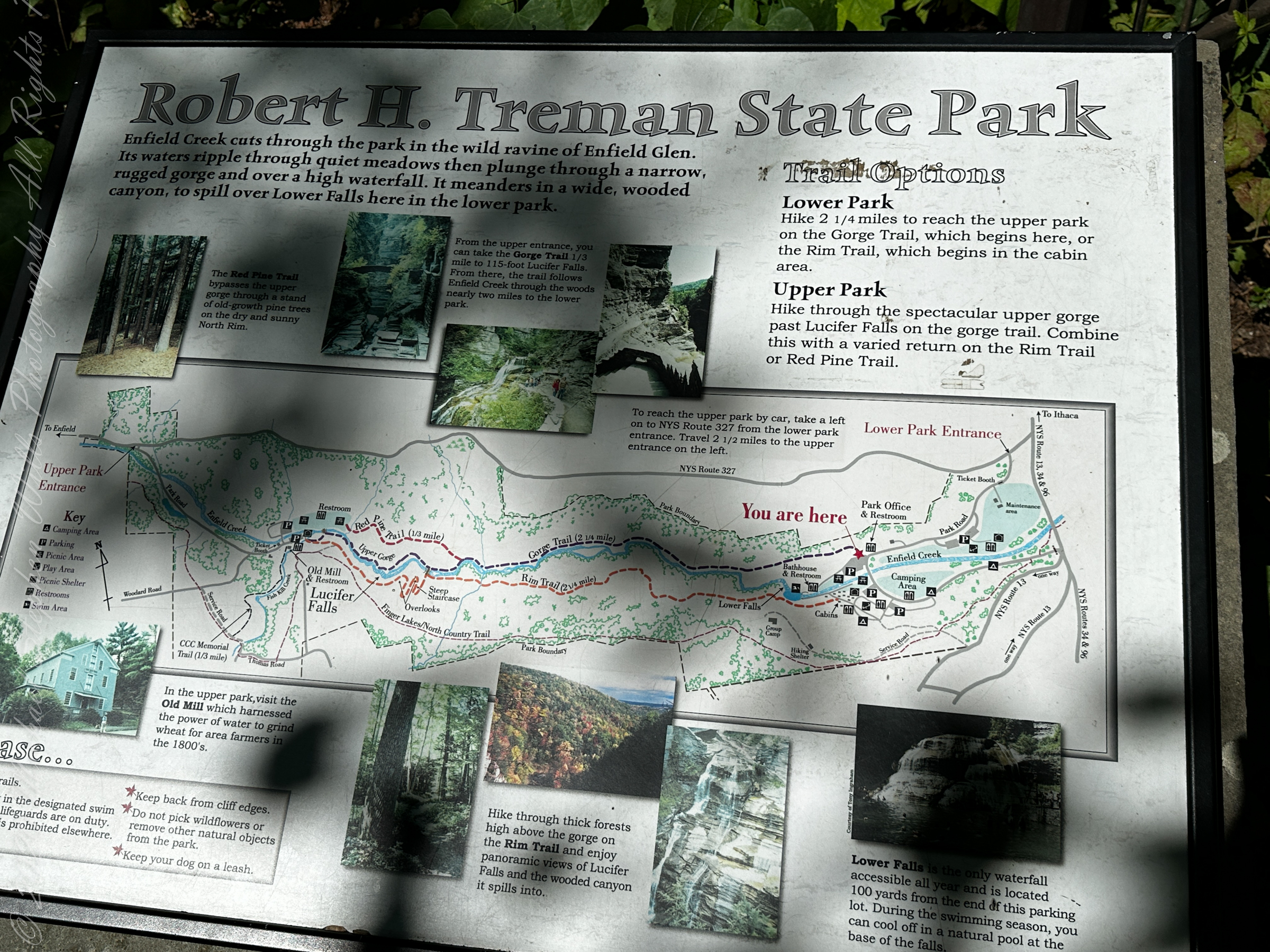

The wind is cool, carrying the first real bite of autumn as I step onto the Finger Lakes Trail from Woodard Road, entering Robert H. Treman State Park. The sounds of rustling leaves underfoot remind me that the season is in full swing, and soon, this vibrant foliage will be a memory. But today, the trees still hold their colors—greens tinged with yellow, brown, and red—forming a canopy that seems to glow in the soft morning light.

The trail is quiet, save for the occasional chirping of birds and the subtle creaking of the trees as they sway in the wind. It’s a perfect time for reflection, and with each step, I feel myself sinking deeper into the peace of this place. Ahead of me, a fallen tree lies on the slope, now part of the earth, slowly being reclaimed by the forest. The log, dotted with moss and fungi, seems like a work of art created by time and nature. I stop to admire it, my fingers grazing the rough bark, now softened with age and decay. It’s a reminder that everything in nature moves in cycles—growth, death, and rebirth.

A few steps further and I find something even more intricate—another log, this one completely overtaken by a delicate layering of lichens and shelf fungi. The growth covers the bark like an elaborate tapestry of greens, grays, and soft whites. It’s beautiful in its own quiet way, and I take a moment to kneel beside it, studying the intricate patterns. Nature has a way of turning even decay into something stunning. I wonder how long it took for these fungi to establish their hold, slowly breaking down the wood, contributing to the endless cycle of life in the forest.

Moving onward, I come across a tall stump—remnants of a once-majestic tree, now shattered. The splintered wood reaches upward like jagged teeth, still sturdy despite the obvious trauma it endured. The raw power of nature is always humbling; trees like this seem so strong and permanent, yet even they can be brought down in an instant. It’s a reminder of life’s fragility, and I feel a sense of reverence standing in its presence, imagining the forces that felled it.

Continuing along the trail, I soon reach a clearing. There, nestled in the grass, is a plaque mounted on a large stone. It marks the site of the Civilian Conservation Corps (C.C.C.) Camp SP-6, Company 1253, which operated here from 1933 to 1935. I pause to read the inscription, which commemorates the young men who lived and worked in this camp during the Great Depression. They carried out public works projects, including improvements to Enfield Glen, Buttermilk Falls, and Taughannock Falls. I imagine the sense of purpose and camaraderie these workers must have felt, building something that would outlast them, even in the midst of hardship.

The plaque is a poignant reminder of the connection between humans and nature. Just as the trees here are part of a larger cycle, so too were the men of the C.C.C. They left their mark on this land, shaping the trails and structures we now take for granted. And yet, like everything in nature, their work is being slowly reclaimed by the forest. The wooden signs marking distances and directions are weathered, moss creeping up their bases, as if the forest itself is gently pulling them back into the earth.

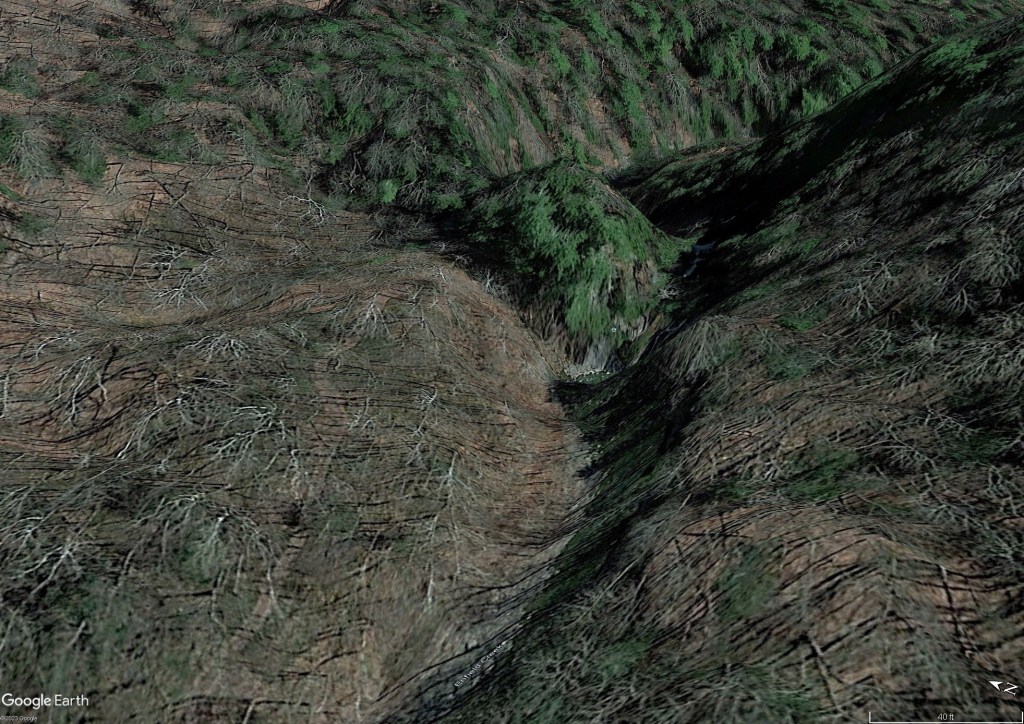

As I cross a small wooden footbridge, recently replaced on the Finger Lakes Trail, I stop to look down at the creek below. The water moves steadily, reflecting the gold and green hues of the trees above. Small waterfalls tumble over rocks, their gentle rush filling the air with a peaceful sound. I watch the water for a while, feeling the pull of time and nature’s persistence.

Standing there, I’m struck by how everything I’ve encountered today, from the fallen trees to the CCC plaque, tells the same story—nature’s quiet persistence, its ability to adapt, reclaim, and renew. I breathe deeply, knowing that while time moves forward and everything changes, the beauty and wisdom of places like this will always remain, if we just take the time to notice.

View from the bridge, downstream Fish Creek