How the builders of Brú na Bóinne clothed themselves

Click Me for the first post of this series.

How the builders of Brú na Bóinne clothed themselves

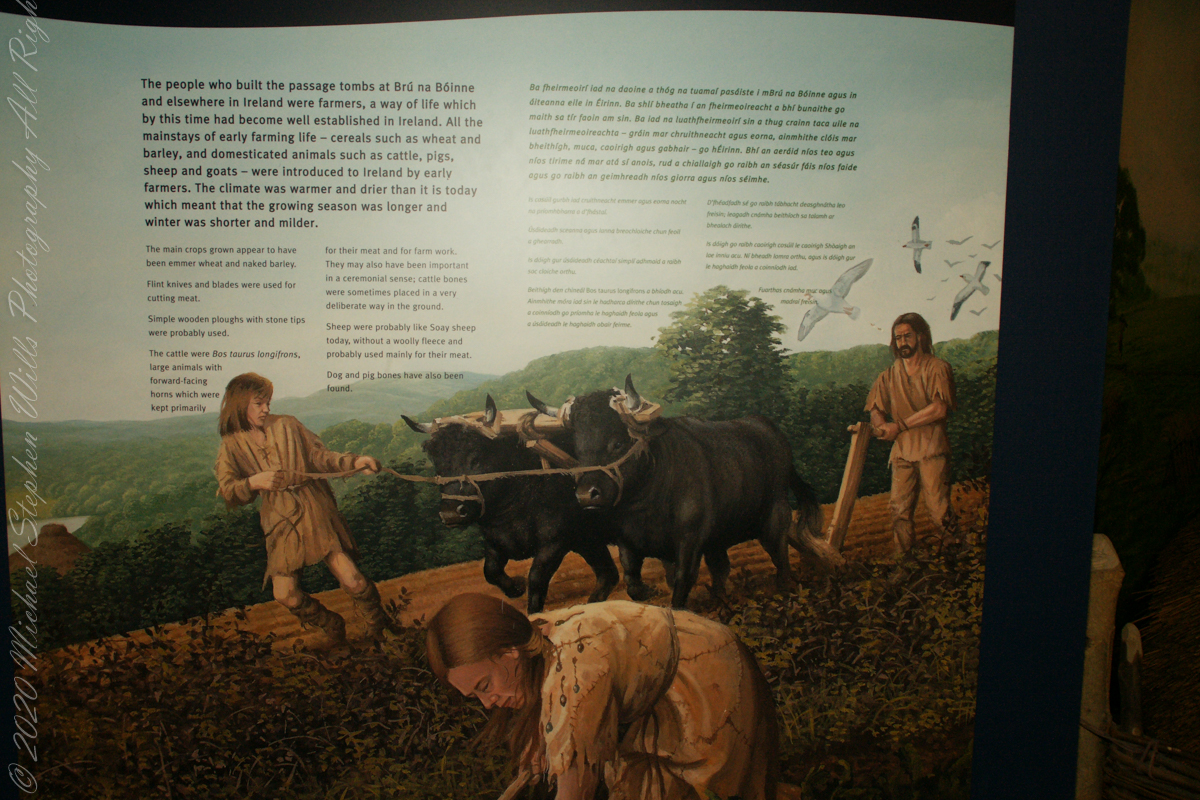

Early Irish farmers introduced crops and domesticated animals, aided by milder climate.

The people who built the passage tombs at Brú na Bóinne and elsewhere in Ireland were farmers, a way of life which by this time had become well established in Ireland. All the mainstays of early farming life — cereals such as wheat and barley, and domesticated animals such as cattle, pigs, sheep and goats — were introduced to Ireland by early farmers. T

he climate was warmer and drier than it is today which meant that the growing season was longer and winter was shorter and milder. The main crops grown appear to have been emmer wheat and naked barley. Flint knives and blades were used for cutting meat. Simple wooden ploughs with stone tips were probably used.

The cattle were Bos taurus longifrans, large animals with forward facing horns which were kept primarily for farm work and meat. Cattle may also have been important in a ceremonial sense; cattle bones were sometimes placed in a very deliberate way in the ground. Sheep were probably like Soay sheep today, without a woolly fleece and probably used mainly for their meat. Dog and pig bones have also been found.

Loughcrew history

In more recent centuries Loughcrew became the seat of a branch of the Norman-Irish Plunkett family, whose most famous member became the martyred St Oliver Plunkett. The family church stands in the grounds of Loughcrew Gardens. With its barren isolated location, Sliabh na Caillí became a critical meeting point throughout the Penal Laws for Roman Catholics. Even though the woods are now gone an excellent example of a Mass Rock can still be seen on the top of Sliabh na Caillí today. The Plunketts were involved in running the Irish Confederacy of the 1640s and were dispossessed in the Cromwellian Settlement of 1652. Their estate at Loughcrew was assigned by Sir William Petty to the Napier Family c.1655. The Napiers are descended from Sir Robert Napier who was Chief Baron of the Exchequer of Ireland in 1593.

Cairnbane East in Ireland, part of the Loughcrew Cairns complex, combines historical significance and folklore, particularly about a witch shaping these megalithic structures.

Here we are looking south, southwest from the north side of Slieve na Calliagh (aka Cairnbane East) toward Cairnbane West. Flowering yellow whin bush is in foreground, white flowering hawthorn trees in distance.

Cairnbane East hill is topped by a fine and accessible passage tomb, Cairn T.

Cairnbane East of the Loughcrew Cairns, known colloquially as “Hag’s Mountain,” nestled amidst the rolling hills of County Meath, Ireland, is a site of profound antiquity that beckons the curious traveler with its enigmatic charm. In this beguiling corner of the world, where history and folklore converge like two ethereal streams, the Loughcrew hills with their cairns rise, sentinels of a bygone age, each with its own tale to tell. But it is the myth of the witch, the “Hag of Loughcrew,” that lend a haunting aura to these ancient megalithic structures, invoking a world where magic and reality danced together in a mesmerizing waltz.

The Loughcrew Cairns, those hallowed remnants of an era long past, are monuments that defy the erosion of time. Constructed during the Neolithic period, they bear witness to the ingenuity of ancient minds and the profound spiritual significance these structures held. These tombs, hewn from the earth and stone, were not mere resting places for the departed, but sacred vessels of cosmic alignment, paying homage to the celestial dance of the heavens.

One of the most enduring legends surrounding Hag’s Mountain is the story of a powerful witch who was said to have constructed the cairns. Cairn T includes a kerbstone known as “the hag’s chair.” According to folklore, this enigmatic figure, known as the “Hag of Loughcrew” or the “Cailleach,” commanded supernatural abilities and controlled the forces of nature. The Cailleach, which translates as ‘old woman’, ‘hag’, and ‘veiled one’, exists in both Irish and Scottish Gaelic, and is an expression of the hag or crone archetype found throughout world cultures. Related words include the Gaelic caileag and the Irish cailín (‘young woman, girl, colleen’), the diminutive of caile ‘woman’, and the Lowland Scots carline/carlin (‘old woman, witch’). The Cailleach is associated with winter, and it is believed that she uses her staff to create the winter snows. In some folk tales it is said that she carried massive stones from distant quarries to build the cairns, working tirelessly through the night and completing tasks that would have been impossible for ordinary mortals.

In these legends the Cailleach’s role in the construction of the cairns is believed to explain their precision and alignment with celestial events. The Cailleach used her magical powers to ensure that the cairns’ passageways perfectly aligned with the sun’s rays during the equinoxes, illuminating the inner chambers in a spectacular display of light and shadow.

Slieve na Calliagh weaves a tapestry where history’s threads intertwine with the shimmering strands of folklore. In its stony silence, it echoes the time when myths and reality were inseparable, when the land bore witness to the otherworldly. As we wander amidst the Loughcrew Cairns, gazing upon the ancient stones, we become travelers in a world where the mystical and the corporeal coalesce, and the stories of the witch endure as whispers in the wind, carried through the ages.

On the Ground in County Meath

On a May afternoon my dear wife, Pam, and I climbed to the summit of in Irish “Sliabh na Caillí” anglicized as “Slieve na Calliagh” translated to the english language as “Hag’s Mountain”, the site of 5000+ year old megalithic monuments. Here you are looking to the northeast with a collapsed tomb to the right foreground. In closeup is a curbstone, one of many laid side to side to form the outer tomb margin. In the middle distance is a hill with additional megalithic ruins, not visible.

Megalithic is an architectural style used throughout the world, between 6,000 and 4,000 years ago in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages. Megalithic ruins are scattered throughout the island and County Meath is especially noted for them.

We stand in Corstown townland, the townlands of Ballinvally is to your left, ahead and to the right is Patrickstown, all in County Meath, Ireland.

In the the long view

On this occasion we will explore a time machine found four miles south of Kells, County Meath, Ireland.

Step into this pool and you, too, can emerge 4,000-odd years later, skin intact, to achieve fame and fortune, a place in a museum and the record books if such exist 6019 AD. Reference the Cashel Man from Cúl na Móna bog near Cashel in County Laois, Ireland who now resides within the National Museum of Ireland.

True, post mortem fame is hollow for the individual. Maybe, attaching your life story engraved on a gold plaque with a gold chain encircling your torso will offset the loss of your bones (dissolved in the acidic waters) and life itself.

The water of this pool is colored dark by long decayed vegetable matter. Beware of walking the bog surface, it is dangerous and destructive to the environment. Pam and I visited Girley Bog on our tour of County Meath, Ireland.

An enormous body of moving water emerges from underground passages

Colorful railings highlight the county border, the centerline of River Cong. To the left is the Cong Salmon Hatchery of County Galway to the right the bridge enters Abby Street of Cong Village, County Mayo. Ahead is where this river, this enormous body of moving water emerges from underground passages through limestone.

Head toward the Ashford Castle Old School House and you will come upon it.

A location from the 1952 film “The Quiet Man”. The house appears on no maps, located on the Ashford Castle grounds. Head toward the Ashford Castle Old School House and you will come upon it. County Mayo, near the Village Cong, Connemara, County Mayo, Republic of Ireland.

I recall there are scenes from “The Quiet Man” featuring characters using this Dutch door, seen to the left in the above photograph and below in a closer shot.

In this photograph the glass etching on entrance, identifying the home, is clearer. Also note the plaque: “Quiet Man House 1951.” Is the plaque wrong? No, while 1952 was the world-wide film release year, filming commenced on June 7, 1951.

Discover the charm of Cong, Ireland, through a stunning sculpture celebrating The Quiet Man. Join me as I explore the town’s cinematic legacy and reflect on the enduring magic of film.

During a May 2014 exploration of the village Cong in County Mayo, Ireland, we encountered this remarkable sculpture that transported me back to one of my favorite classic films, “The Quiet Man.” The bronze statue, depicting John Wayne’s character, Sean Thornton, carrying Maureen O’Hara’s Mary Kate Danaher, stands against the backdrop of the town, a visual homage to the cinematic legacy that has become intertwined with Cong’s identity.

As I stood before the sculpture, memories of watching The Quiet Man flooded back. The Quiet Man, with its vibrant depiction of Irish culture and scenery, had always held a special place in my heart. It’s a story of love, cultural clashes, and the journey of a man returning to his roots, themes that resonate deeply within the lush landscapes of County Mayo. Cong served as the primary filming location, and the town has embraced this legacy wholeheartedly, turning the film into a cornerstone of its identity.

The sculpture, created by Mark Rode, who has a foundry an hour away in Swinford, was installed the year before, 2013, yet it felt as though it had always been there, seamlessly blending with the surroundings. Rode’s work captures the essence of the characters with remarkable detail. In The Quiet Man, the scene where Sean carries Mary Kate in his arms takes place after he retrieves her from the train station. This moment symbolizes their reconciliation and is a pivotal scene in the film, capturing their renewed bond and Sean’s determination to stand up for their relationship. The piece celebrates not just the film, but also the spirit of the town and its connection to cinematic history.

Mark Rode, known for his ability to bring characters to life through sculpture, has a unique talent for capturing the essence of his subjects. His works often reflect a deep understanding of human emotion and storytelling, qualities that shine through in this particular piece. The installation of the sculpture was met with excitement from both locals and visitors, further cementing Cong’s status as a beloved tourist destination.

Reflecting on our visit, I realized how much this small town had embraced its role in cinematic history. The streets of Cong are dotted with nods to The Quiet Man—from themed shops to plaques marking filming locations. Each element serves as a reminder of the film’s impact on the town and its people. The statue stands as a centerpiece, inviting fans of the film to relive its magic while introducing new generations to its charm.

I couldn’t help but meditate on the lasting impact of art and film on a community. The installation of this sculpture not only celebrates a beloved movie but also invigorates the town’s economy through tourism, drawing visitors eager to walk in the footsteps of their favorite characters. It’s a testament to the power of storytelling and its ability to transcend time, connecting people across generations and cultures.

The statue of Sean and Mary Kate in Cong is a symbol of the town’s vibrant history and its enduring connection to the film. Mark Rode’s creation captures this essence beautifully, inviting all who visit to pause, reminisce, and celebrate the intertwining of art and life in this picturesque Irish village.

Here presented are two versions of the same image. One cropped. Please leave a comment stating which you prefer and why. Thank You

Use this slide show, flip back and forth to compare the images, reach a conclusion on which you prefer.

The Great Famine had profound social, cultural, and political impacts on Ireland and its relationship with Britain. It led to a significant decline in the Irish population due to death and mass emigration and is remembered as one of the darkest periods in Irish history. The event also left deep scars on the collective memory of the Irish people and played a role in the growth of Irish nationalism and the push for Irish independence in the following decades

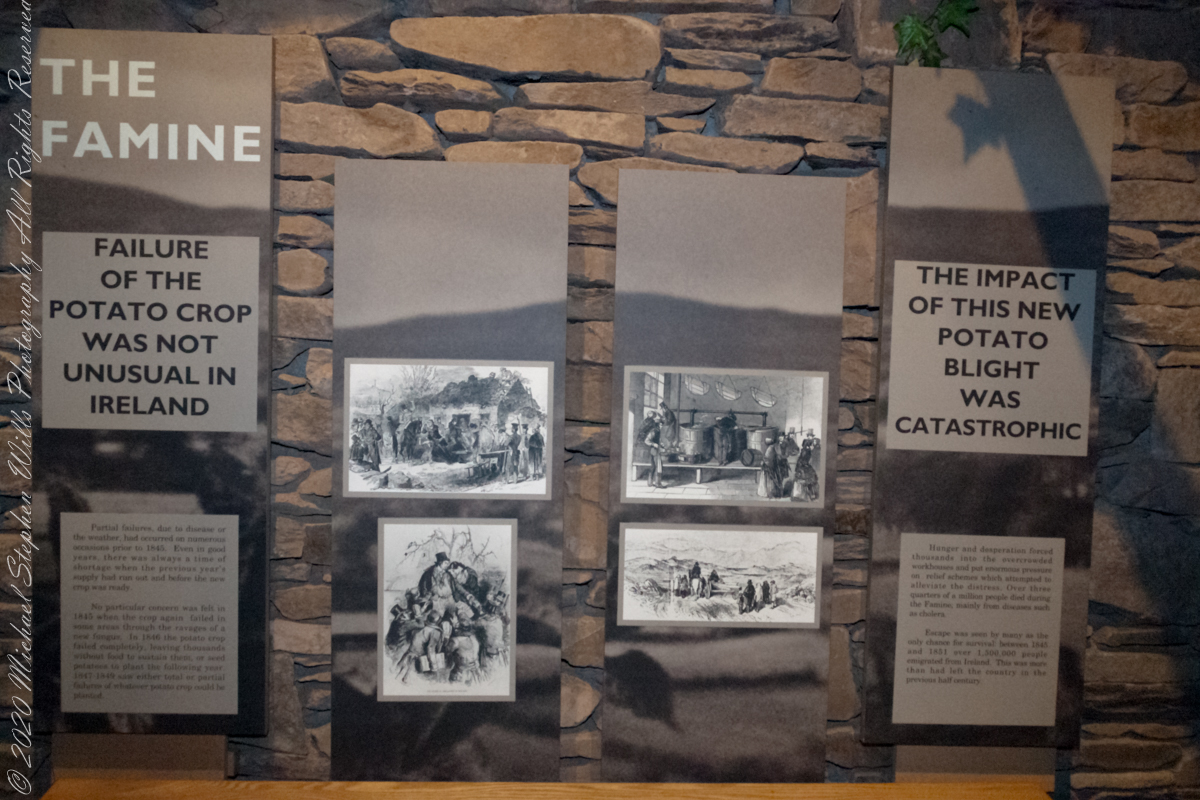

“Partial failures, due to disease or the weather, had occurred on numerous occasions prior to 1845. Even in good years, there was always a time of shortage when the previous year’s supply had run out and before the new crop was ready.”

“No particular concern was felt in 1845 when the crop again failed in some areas through the ravages of a new fungus. In 1846 the potato crop failed completely, leaving thousands without food to sustain them, or seed potatoes to plant the following year. 1847 – 1849 saw either total or partial failures of whatever potato crop could be planted.”

“Hunger and desperation forced thousands into the overcrowded workhouses and put enormous pressure on relief schemes which attempted to alleviate the distress. Over three quarters of a million people died during the Famine, mainly from diseases such as cholera. Escape was seen by many as the only change for survival: between 1845 and 1851 over 1.5 million people emigrated from Ireland. This was more than had left the country in the previous half century.”

The Great Famine of Ireland, often referred to as the “Irish Potato Famine,” occurred between 1845 and 1852, with the most acute suffering taking place between 1847 and 1849. The causes of this devastating period in Irish history are multifaceted and debated among historians, but the following are generally acknowledged as the primary factors:

Potato Blight (Phytophthora infestans): The immediate cause of the famine was a potato disease known as late blight. The potato was a staple crop in Ireland, and for many poor Irish, it was the primary source of nutrition. The blight destroyed the potato crop year after year, leading to widespread hunger.

Over-reliance on a Single Variety of Potato: The Irish mainly grew a type of potato called the “Lumper,” which was particularly susceptible to the blight. This lack of genetic diversity made the entire crop more vulnerable to disease.

Land Ownership and Tenancy: Most of the land in Ireland was owned by a small number of landlords, many of whom were absentee, living in England. The Irish Catholic majority often worked as tenant farmers, living on small plots of land and paying rent to these landlords. The land was subdivided among heirs, leading to plots becoming increasingly smaller and less productive over generations.

British Colonial Policies: The relationship between Ireland and Britain played a significant role in exacerbating the famine’s effects. Some British policies and economic theories at the time discouraged intervention. For instance:

Corn Laws: These tariffs protected British grain producers from cheaper foreign competition, making grain more expensive and less accessible for the starving Irish.

Economic Beliefs: The prevailing laissez-faire economic philosophy of the time held that markets should be allowed to self-regulate without government intervention.

Exports: Even as the famine raged, Ireland continued to export food (like grain, meat, and dairy) to Britain, which was a source of controversy. Many felt these exports should have been halted or reduced to feed the starving Irish population.

Inadequate Relief Efforts: While the British government did undertake some relief measures, such as opening public works projects and distributing maize (known as “peel’s brimstone”), these efforts were often insufficient, mismanaged, or too late. The public works projects sometimes did not lead to meaningful infrastructure improvements and instead focused on tasks like building roads that led nowhere.

Social and Cultural Factors: Discrimination against the Irish Catholics by the Protestant English elite, language barriers (many Irish spoke only Gaelic), and distrust between the local population and English officials further complicated relief efforts.

The Great Famine had profound social, cultural, and political impacts on Ireland and its relationship with Britain. It led to a significant decline in the Irish population due to death and mass emigration and is remembered as one of the darkest periods in Irish history. The event also left deep scars on the collective memory of the Irish people and played a role in the growth of Irish nationalism and the push for Irish independence in the following decades.

Reference: text in quotes is from “The Famine” poster. Cobh Heritage Center, May 2014.

Copyright 2023 Michael Stephen Wills All Rights Reserved