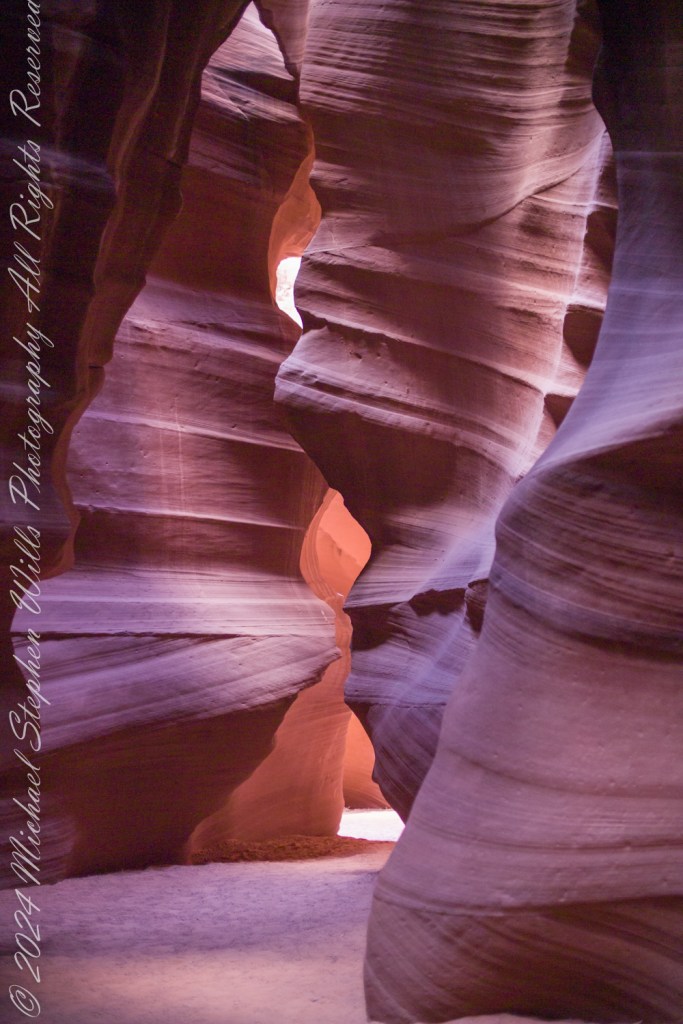

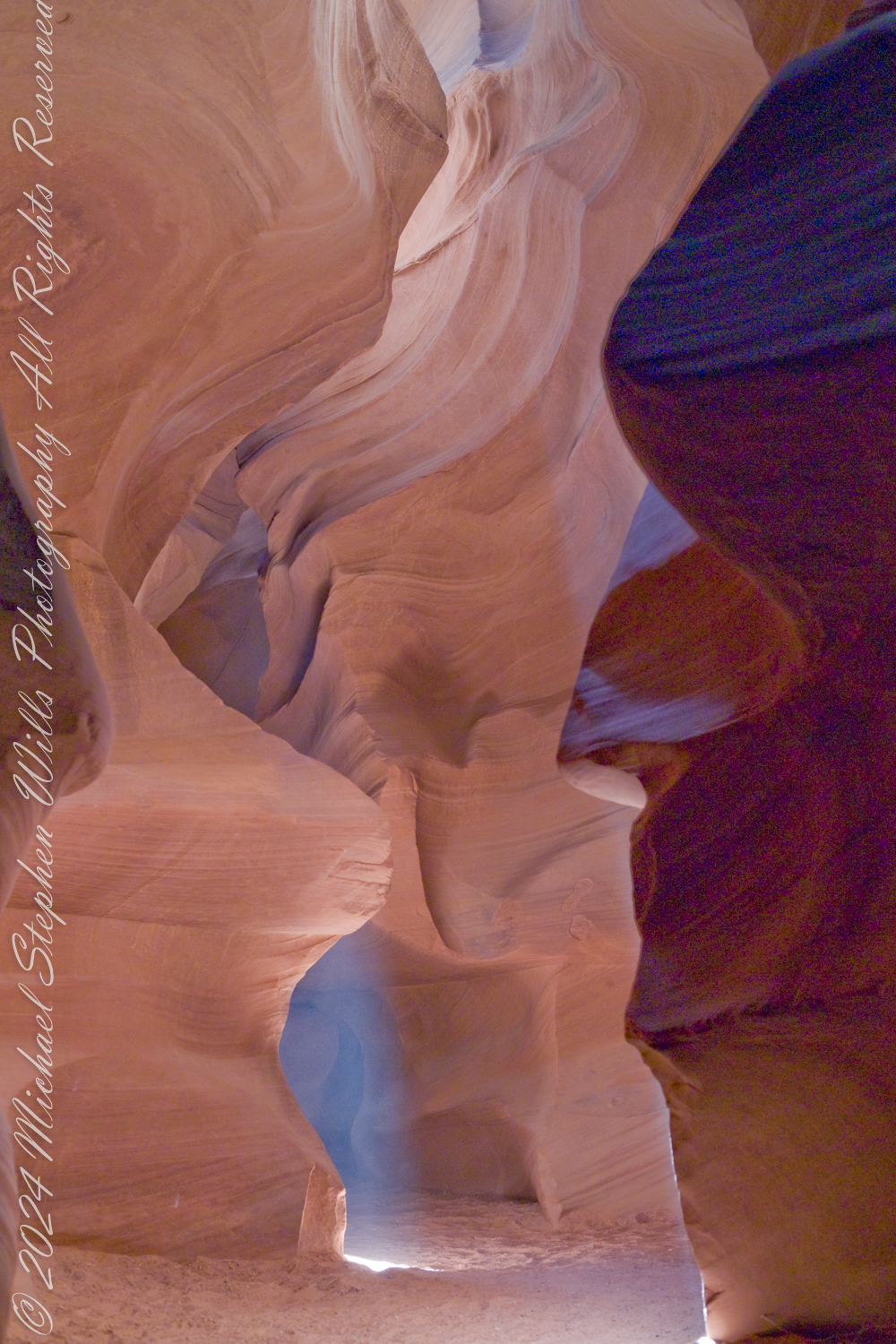

Enveloped by shadows and light in the stillness of Antelope Canyon the air carries silence—vast and ancient—interrupted only by the whispers of grains shifting under unseen currents. Here the red rock of the northwestern corner of the Navajo Nation was pulverized into sand by the action of wind, water, sun, and cold. The walls, carved by patient time, cradle the moment as if holding a sacred breath.

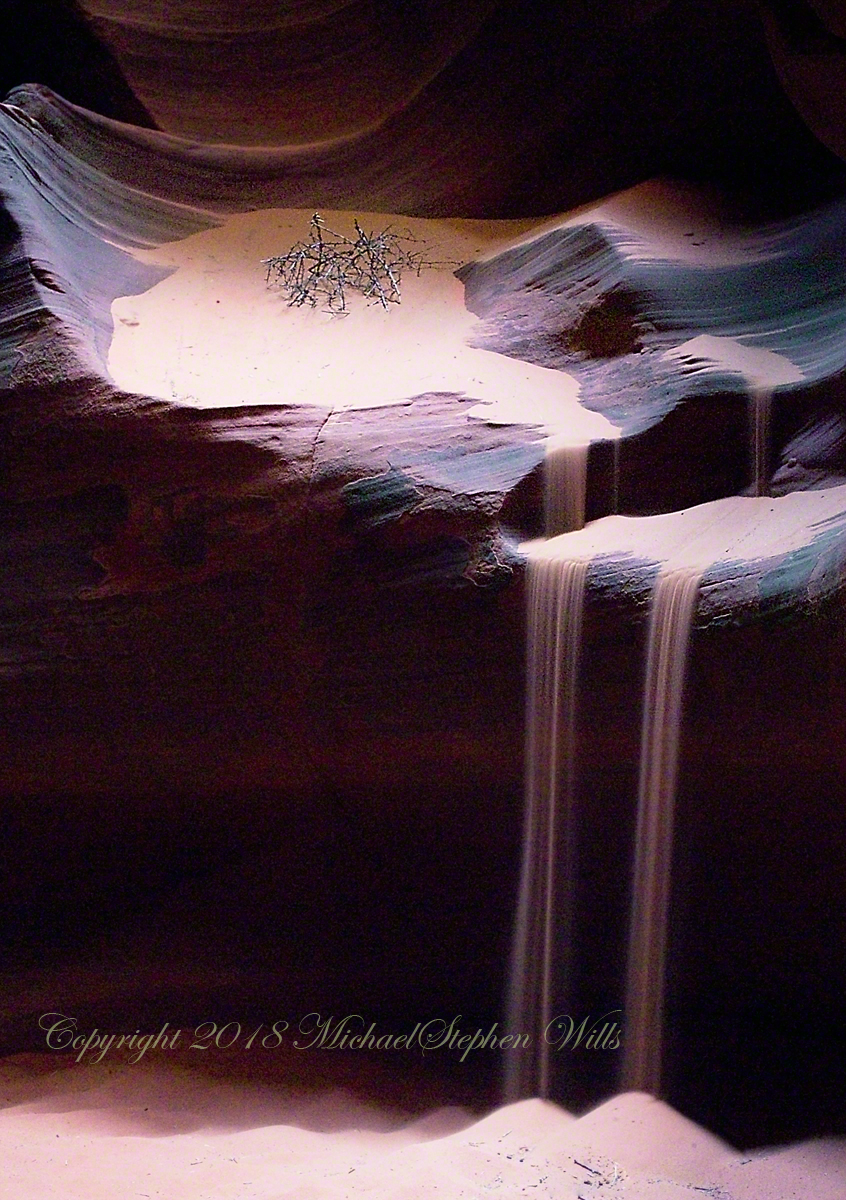

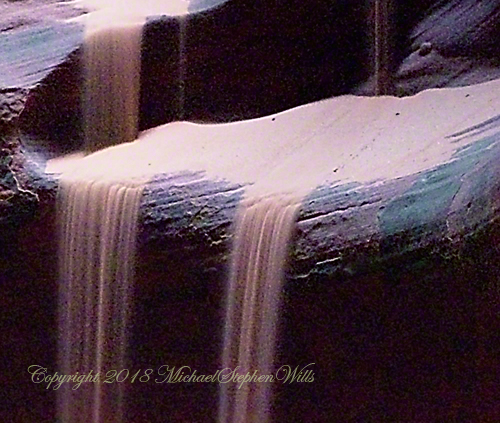

Antelope Canyon, timeless and transient, has summoned me to witness something unique—a dance between light and matter. The delicate, insistent sand flows like water from a carved bench, shaping the scene with quiet power. It tumbles as if alive, forming ephemeral cascades, revealing that erosion is not destruction but transformation. Each grain a story—a fragment of the ages, polished smooth by untold moments of pressure and release.

A Slot of Shadows and Light

I wait in the dry darkness of upper Antelope Canyon for the perfect moment to capture the spirit of the place. Light penetrates the narrow slot above, a thin beam spilling through the crevice, drawn by something deep below. In this confined space, sunlight becomes an entity. It touches the red sand and animates the space, revealing stone textures and the fleeting movement of sand in freefall.

The play between dark and light reminds me that beauty often lies in contrast. The polished walls that surround me were once jagged, raw stone. They have become smooth under nature’s relentless touch—proof that endurance shapes elegance. The canyon’s walls, though fixed in place, seem to sigh as the sand slips over them, embodying a paradox of permanence and impermanence.

An Elemental Meditation

I am a visitor as well as part of a conversation held in languages older than words—spoken by rock, sand, shadow, and light. I sense the ancient stories etched into the stone and carried within each grain that spills like an hourglass. Here, nothing is wasted; everything contributes to a continuous process of becoming. The sand, which once formed the walls, now shapes the canyon floor, each element recycling into the next chapter of this landscape’s life.

The act of waiting for a right moment teaches me that patience is both passive and an active engagement with time. I am reminded that what I witness will never be exactly the same again. Even though the canyon may stand for millennia, each second contains a uniqueness. The sand cascading before my eyes will settle, be disturbed, and flow again—but never in quite the same way.

Capturing the Spirit of Place

I set the camera on a rented tripod, knowing photography is an imperfect attempt to hold onto what cannot be possessed. This place does not belong to me—it belongs to itself, shaped by forces far greater than any human hand. My role is not to own the scene but to honor it, to acknowledge its fleeting magnificence by framing a moment within the lens.

The shutter clicks, the cascade of sand becomes immortalized held in that instant. Yet I know that the photograph, while capturing the image, will not fully encompass the spirit of what I have experienced. This place is a meditation, a reminder that life itself flows in ways we cannot control. Like the red sand, we are carried by forces—sometimes gentle, sometimes fierce—shaping and reshaping us through time.

As I gaze at the sand, a quiet sense of reverence flows through me. This moment, like the grains tumbling in front of me, is already slipping into the past. But in its passing, it leaves behind something intangible yet enduring—a memory of beauty found not in permanence but in change.

Click this link for my Fine Art Photography gallery.

Click this link for another Arizona post, “A Dry Piece of Paradise.”