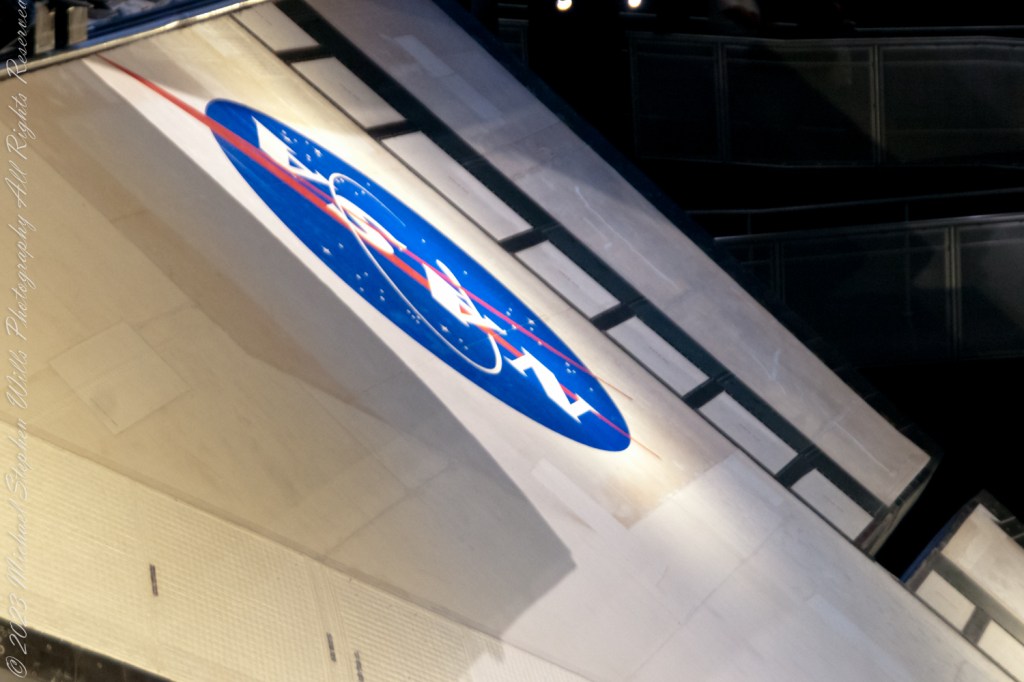

Imagine, if you will, stepping onto the grounds of NASA, where the air buzzes with the legacy of space exploration and the spirit of human achievement. It’s a place where dreams of the cosmos turn into reality. Our 2017 Launch Director tour not only brought us face-to-face with the marvels of space travel but allowed me to delve into the intricate details of one of NASA’s most iconic spacecraft: the Space Shuttle Atlantis. In this episode 6 of our adventure, we continue exploring the engineering marvel that is Atlantis, focusing on its wings, rear stabilizer, and onboard engines—elements critical to its legendary missions.

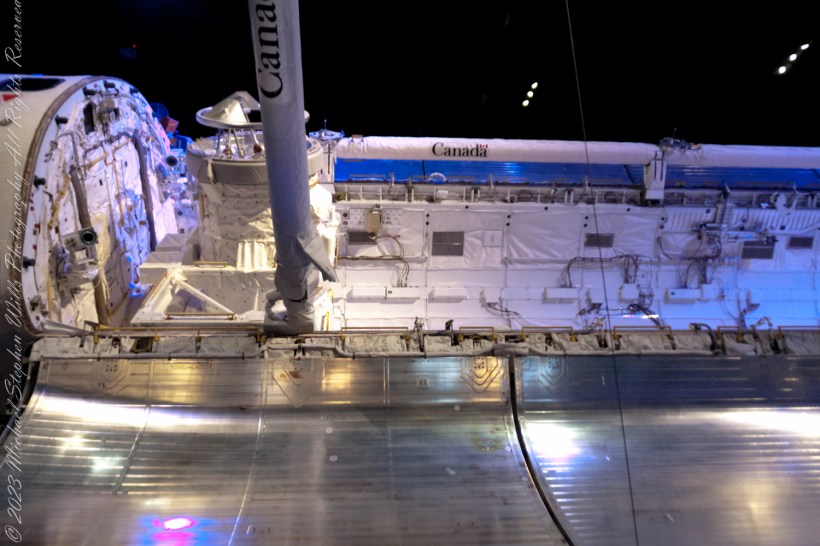

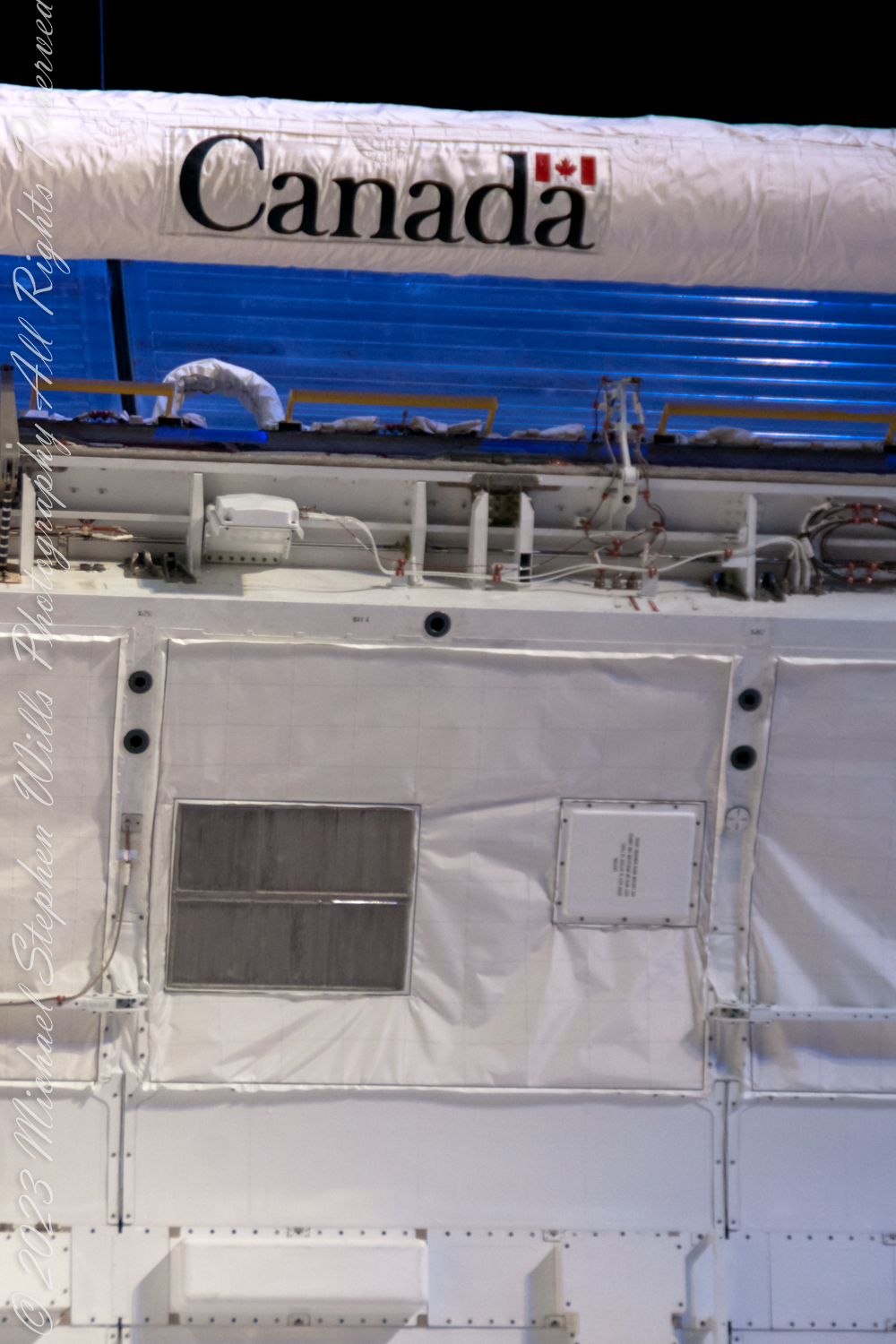

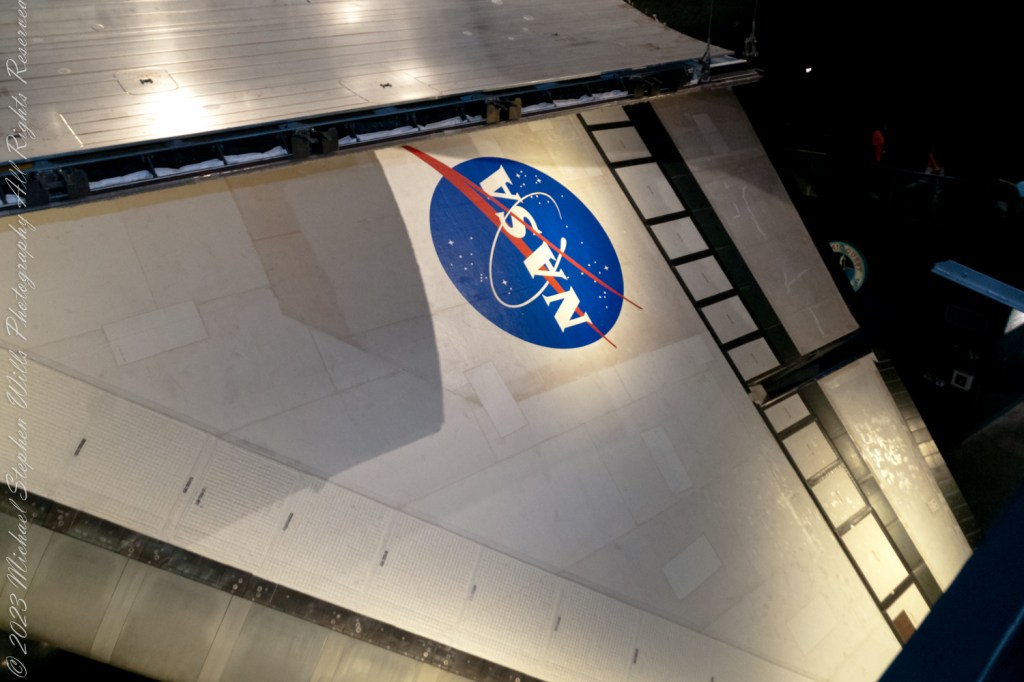

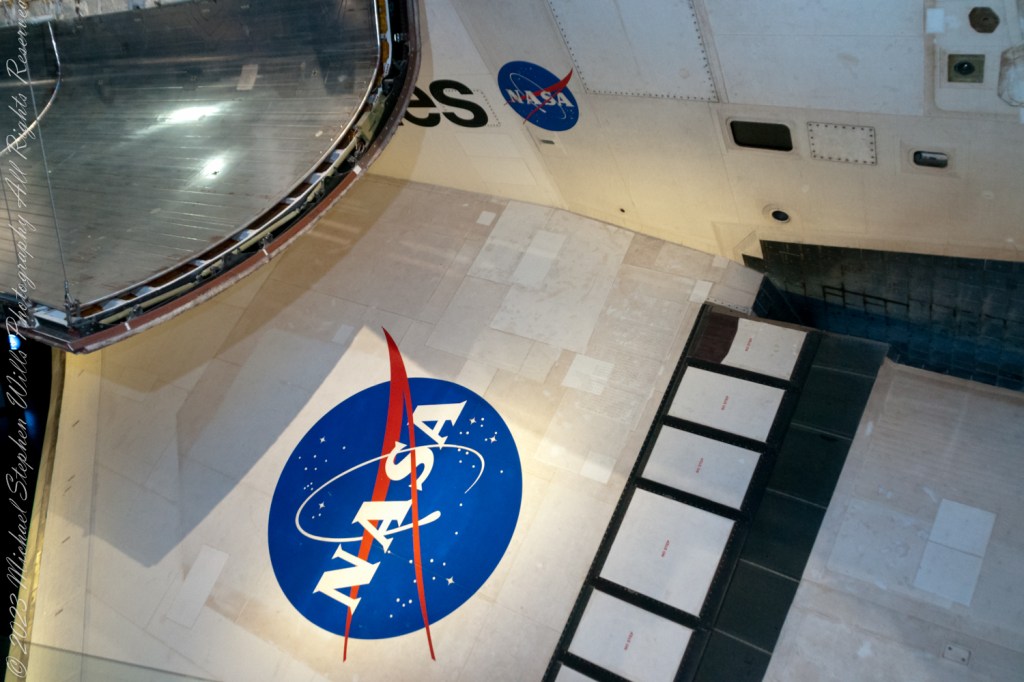

The Space Shuttle Atlantis, a name synonymous with discovery and exploration, represents a pinnacle of human ingenuity. As you walk around the Atlantis exhibit, you can’t help but be awed by the shuttle’s design, particularly its wings. The wings of Atlantis, with a wingspan of about 78 feet, are not just structures of metal and composite materials; they are the shuttle’s lifeline during re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere. These delta-shaped wings are designed to withstand the scorching temperatures of re-entry, allowing Atlantis to glide back to Earth with grace and precision. The material covering the wings, known as the Thermal Protection System (TPS), consists of thousands of heat-resistant tiles and reinforced carbon-carbon panels, safeguarding the shuttle and its crew from temperatures exceeding 1,650 degrees Celsius.

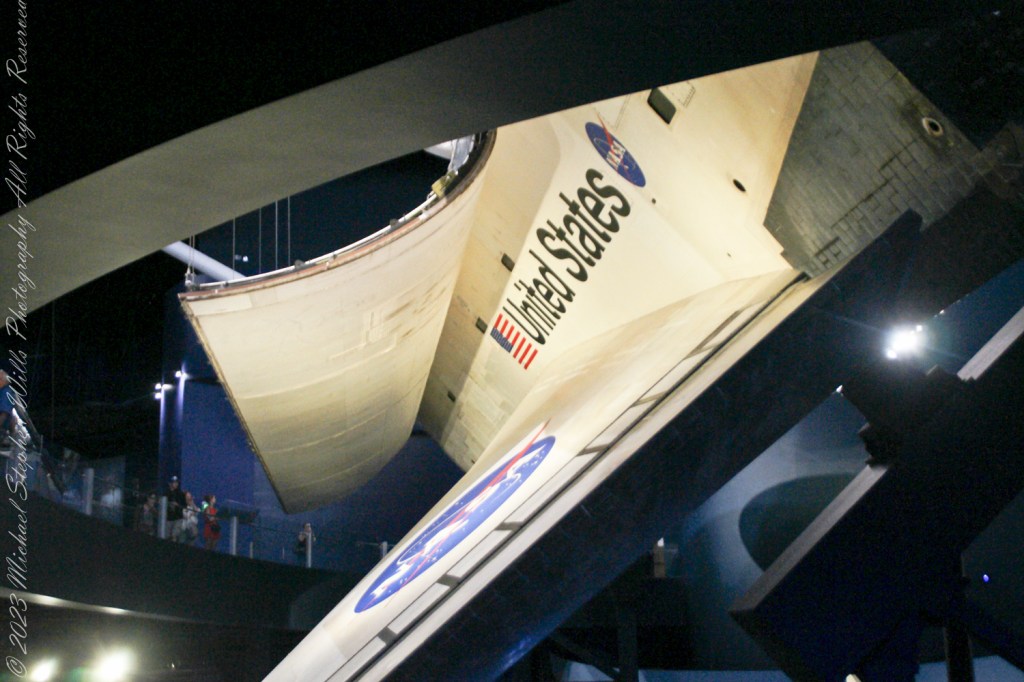

As your gaze shifts towards the rear of Atlantis, the vertical tail fin, or the rear stabilizer, commands attention. Standing about 17 feet tall, this stabilizer is more than just a rudder; it’s a critical component for maintaining the shuttle’s stability during the different phases of its mission. During the launch, it helps keep the shuttle on course as it ascends through the atmosphere. In space, it plays a minimal role, but upon re-entry, it becomes vital again, ensuring the shuttle remains stable and oriented correctly as it descends through the atmosphere, allowing for a safe landing.

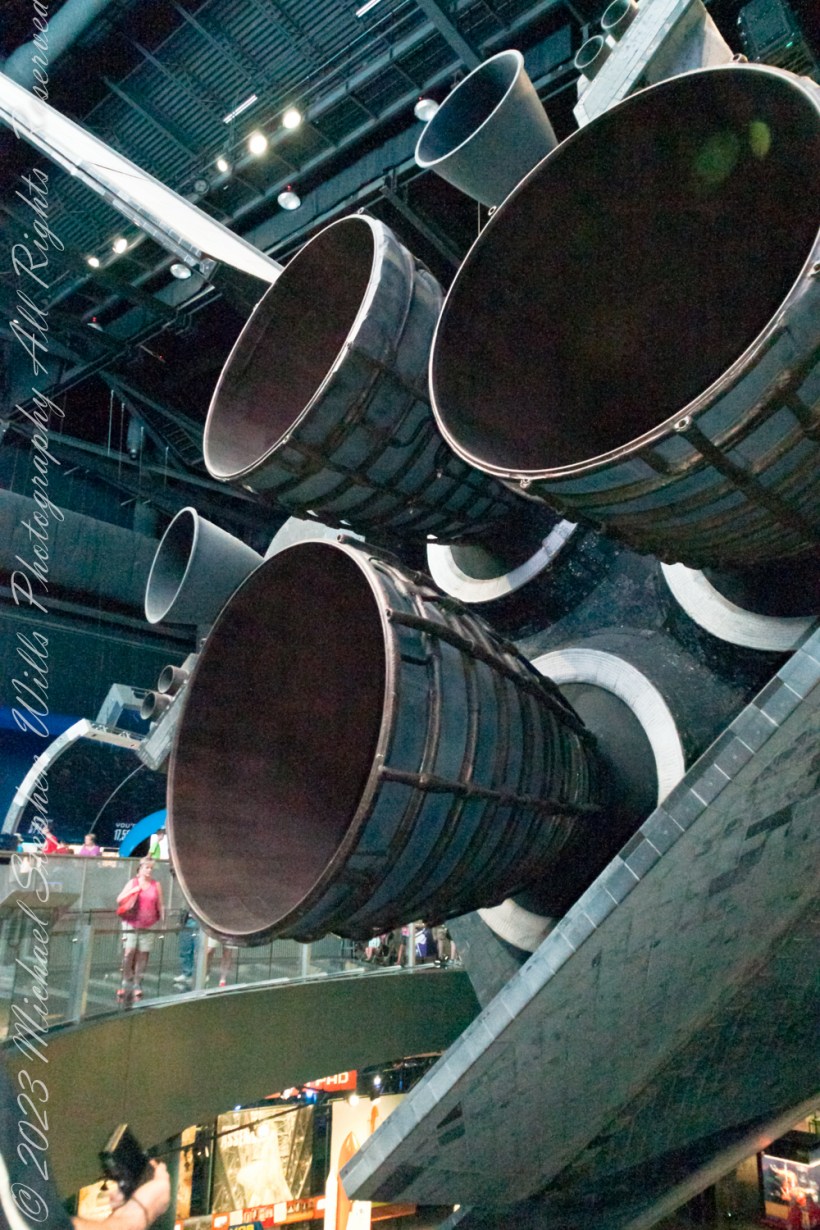

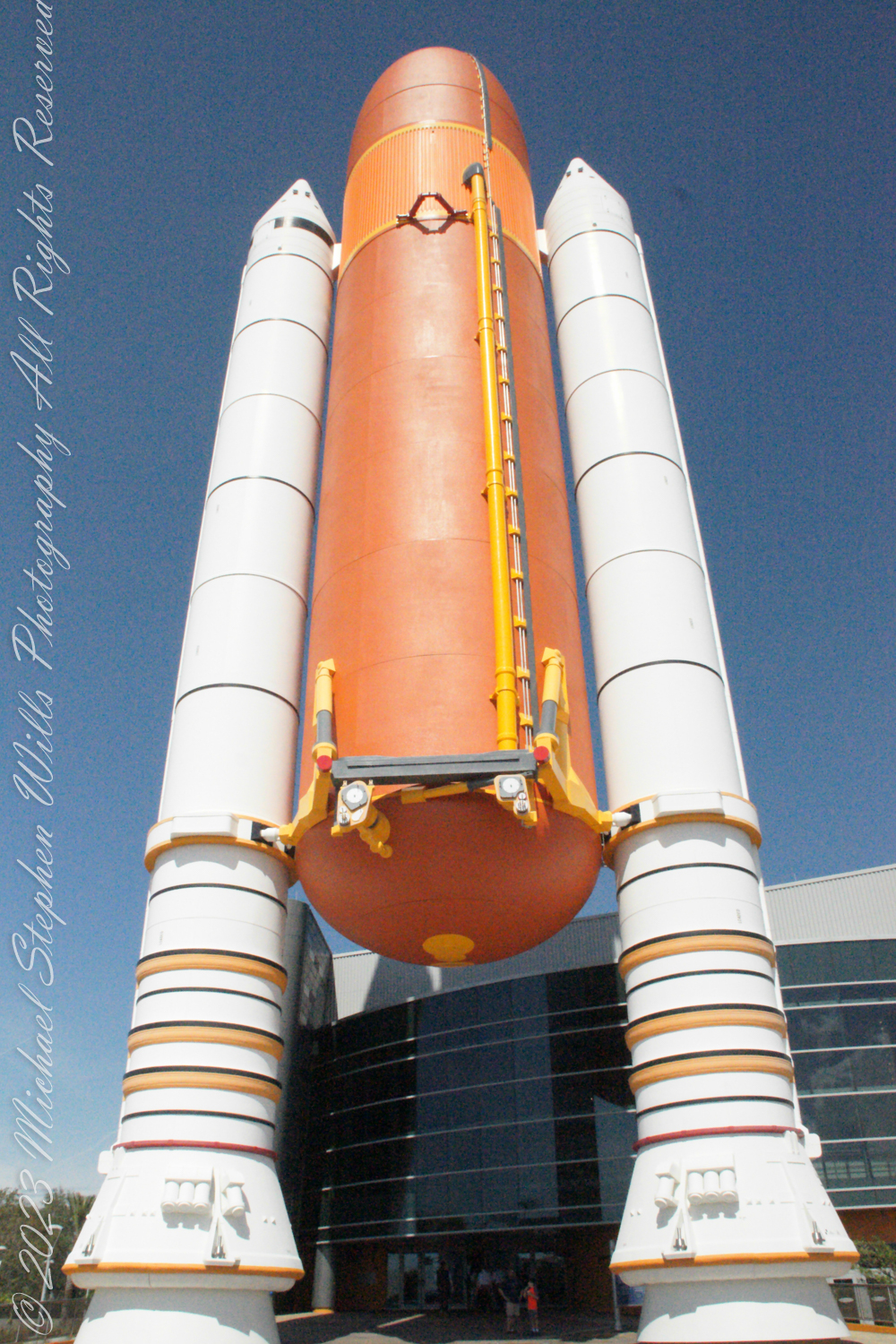

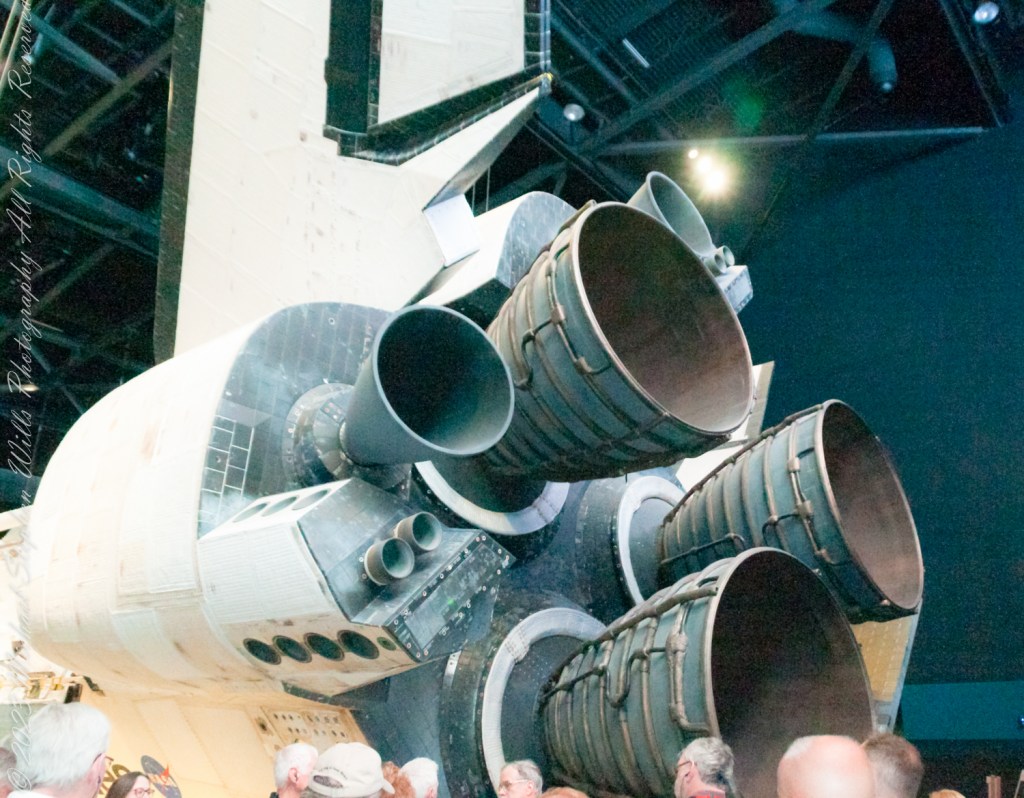

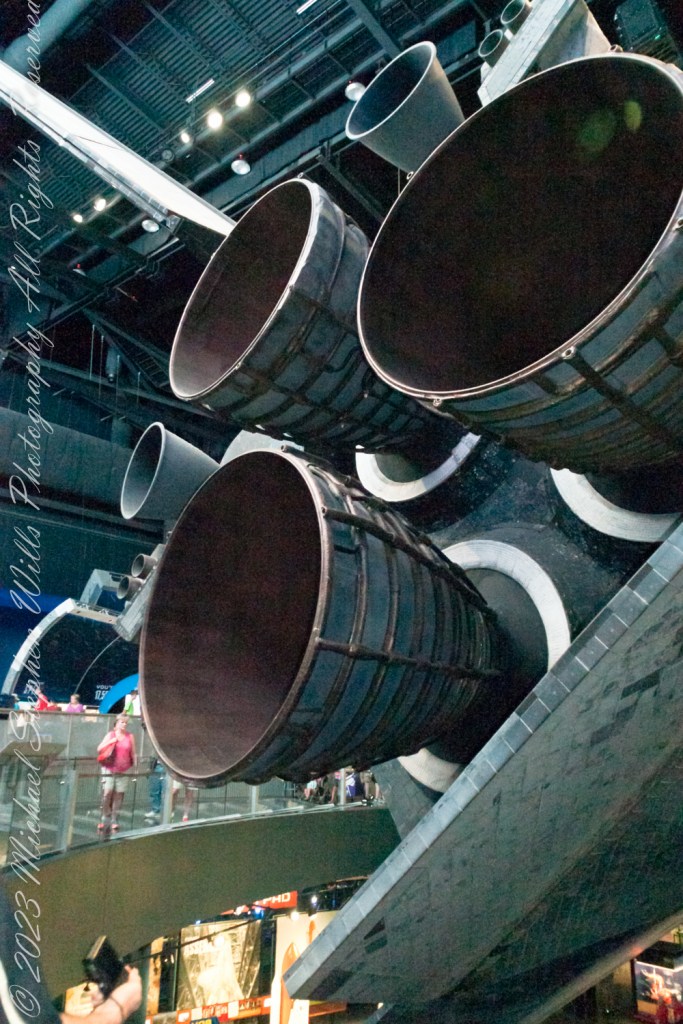

In this exploration of Atlantis, after the wings and stabilizer, we encounter the heart of the shuttle’s propulsion system: its onboard engines. The Space Shuttle Main Engines (SSMEs), three in total, are marvels of engineering, capable of producing a combined thrust of over 1.2 million pounds. These liquid-fueled engines play a crucial role in propelling the shuttle from the launch pad into orbit. What’s fascinating is their ability to throttle up or down depending on the phase of the launch, providing the precise amount of power needed at any given moment. The engines are fed by the External Tank, the only part of the shuttle not reused, which carries the liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen needed for combustion. Upon reaching orbit, the Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) engines take over, allowing Atlantis to navigate the vacuum of space with finesse, adjusting its orbit and facilitating the meticulous maneuvers required for satellite deployment or docking with the International Space Station.

Walking away from the Atlantis exhibit, what stays with you is not just the sight of this magnificent spacecraft but an appreciation for the ingenuity and dedication that went into its design. Every wing, every tile on the stabilizer, and every roar from the engines tell a story of human curiosity, the drive to explore beyond our confines, and the relentless pursuit of knowledge. The Space Shuttle Atlantis is more than a machine; it’s a symbol of what humanity can achieve when we dare to dream big and work tirelessly towards those dreams. So, as you look up at the night sky, remember the wings that carried our dreams, the stabilizer that kept us on course, and the engines that propelled us into the unknown, reminding us that the final frontier is not so final after all.