As I strolled through the sun-dappled glade, my eyes were drawn to a magnificent tree standing sentinel at the edge of the clearing. Its broad canopy spread like a green umbrella, casting a generous shade over the picnic bench below. Intrigued by its commanding presence, I approached, eager to unravel the secrets of this arboreal giant. Little did I know that this encounter would lead me on a journey through history, etymology, and the myriad uses of the American Basswood.

The American Basswood, or Tilia americana, is a tree steeped in history and lore. Its name, “Basswood,” is derived from the word “bast,” referring to the inner bark of the tree, which is known for its fibrous and pliable nature. This etymology hints at the tree’s historical uses, which I would soon discover are as rich and varied as the foliage above me.

As I examined the leaves, I was struck by their heart-shaped form, a feature that has made the Basswood a symbol of love and romance in various cultures. The leaves were smooth and slightly serrated at the edges, with a deep green hue that seemed to capture the essence of summer. Hanging delicately from the branches were clusters of small, round buds, hinting at the tree’s flowering potential. These flowers, I would later learn, are not just beautiful but also aromatic, attracting bees and other pollinators with their sweet fragrance.

The history of the American Basswood in America is intertwined with the lives of indigenous peoples and early settlers. Native Americans valued the Basswood for its soft, easily worked wood and its inner bark, which they used to make ropes, mats, and other essential items. The tree’s wood, known for being lightweight and finely grained, was perfect for carving and crafting tools, utensils, and even ceremonial masks. This versatility made the Basswood an integral part of daily life and cultural practices.

With the arrival of European settlers, the uses of Basswood expanded. Settlers quickly recognized the tree’s potential, using its wood for a variety of applications. The soft, yet sturdy wood was ideal for making furniture, musical instruments, and even crates and boxes. Its workability and smooth finish made it a favorite among craftsmen and artisans. I imagined the hands of these early Americans, shaping and molding the wood, breathing life into their creations.

As I continued to explore the tree, I was drawn to the small, green fruits hanging from slender stems. These fruits, known as nutlets, are encased in a leafy bract that aids in their dispersal by wind. This ingenious natural design ensures the propagation of the species, allowing new generations of Basswoods to take root and flourish.

Curious about the tree’s name, I delved into its etymology and discovered an interesting linguistic journey. In England and Ireland, the Basswood is commonly referred to as the “Lime Tree.” This name does not relate to the citrus fruit tree but instead comes from the Old English word “Lind,” related to the German word “Linde.” Both terms historically referred to trees of the Tilia genus. Over time, “Lind” evolved into “Lime,” influenced by phonetic changes and regional dialects, solidifying the term “Lime Tree” for Tilia species in these regions. Despite sharing the same common name, the Tilia “Lime Tree” and the citrus “Lime Tree” belong to entirely different plant families.

The American Basswood’s significance extends beyond its practical uses. The tree has found a place in American culture and literature, often symbolizing strength, resilience, and longevity. Its towering presence and expansive canopy make it a popular choice for parks and public spaces, where it provides shade and beauty. I thought of the many people who must have sought refuge under its branches, finding solace and inspiration in its quiet strength.

In addition to its cultural and historical significance, the Basswood also plays a crucial ecological role. Its flowers are a vital source of nectar for bees, making it an essential component of local ecosystems. Beekeepers, in particular, value the Basswood for the high-quality honey produced from its nectar, known for its delicate flavor and aroma. The tree’s leaves and bark also provide habitat and food for various wildlife, contributing to the biodiversity of the area.

Pollination is a critical aspect of the American Basswood’s lifecycle, and a variety of insects are drawn to its fragrant, nectar-rich flowers. Honeybees (Apis mellifera) are among the most significant pollinators, their presence around the Basswood a testament to the tree’s importance in the ecosystem. These industrious bees not only gather nectar but also facilitate the pollination process, ensuring the production of seeds. Bumblebees (Bombus spp.) also play a crucial role, utilizing their unique buzz-pollination technique to effectively transfer pollen within the flowers.

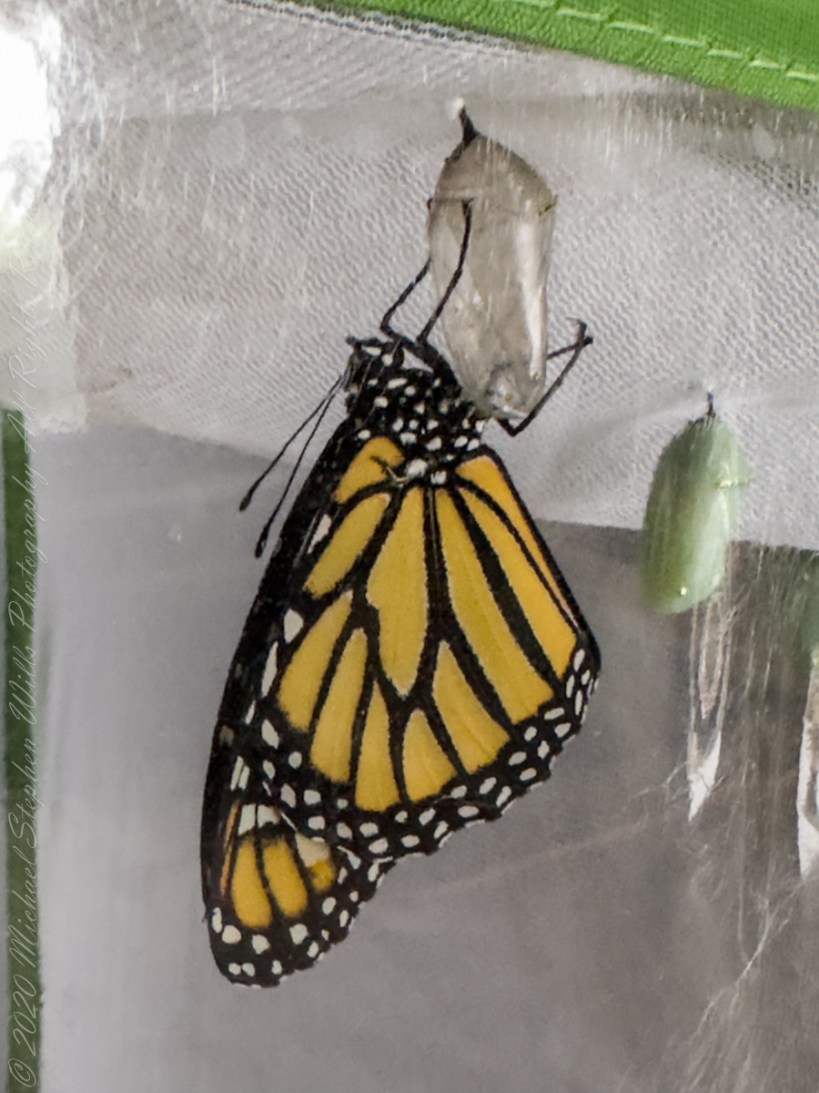

Additionally, native bees such as sweat bees (Halictidae), mining bees (Andrenidae), and leafcutter bees (Megachilidae) are frequent visitors, drawn by the abundant nectar and pollen. Butterflies, while not as significant as bees, contribute to the pollination process, adding a touch of grace as they flutter from flower to flower. Moths, particularly those active in the evening, are another group of pollinators, their nocturnal activity complementing the daytime efforts of bees and butterflies. Hoverflies (Syrphidae), also known as flower flies, are attracted to the nectar and aid in the pollination, showcasing the diverse array of insects that rely on the Basswood.

Reflecting on my discovery, I realized the American Basswood is a living testament to the interconnectedness of nature and human history. Its presence in the landscape is a reminder of the many ways in which plants and trees shape our lives, providing resources, inspiration, and a connection to the natural world.

As I left the shade of the Basswood and continued my walk, I felt a deep sense of gratitude for the opportunity to learn and connect with this remarkable tree. Its story is a reminder of the importance of preserving and cherishing the natural world, ensuring that future generations can continue to discover and appreciate the wonders of the American Basswood.