Exploring the Formation of Whelk Shells

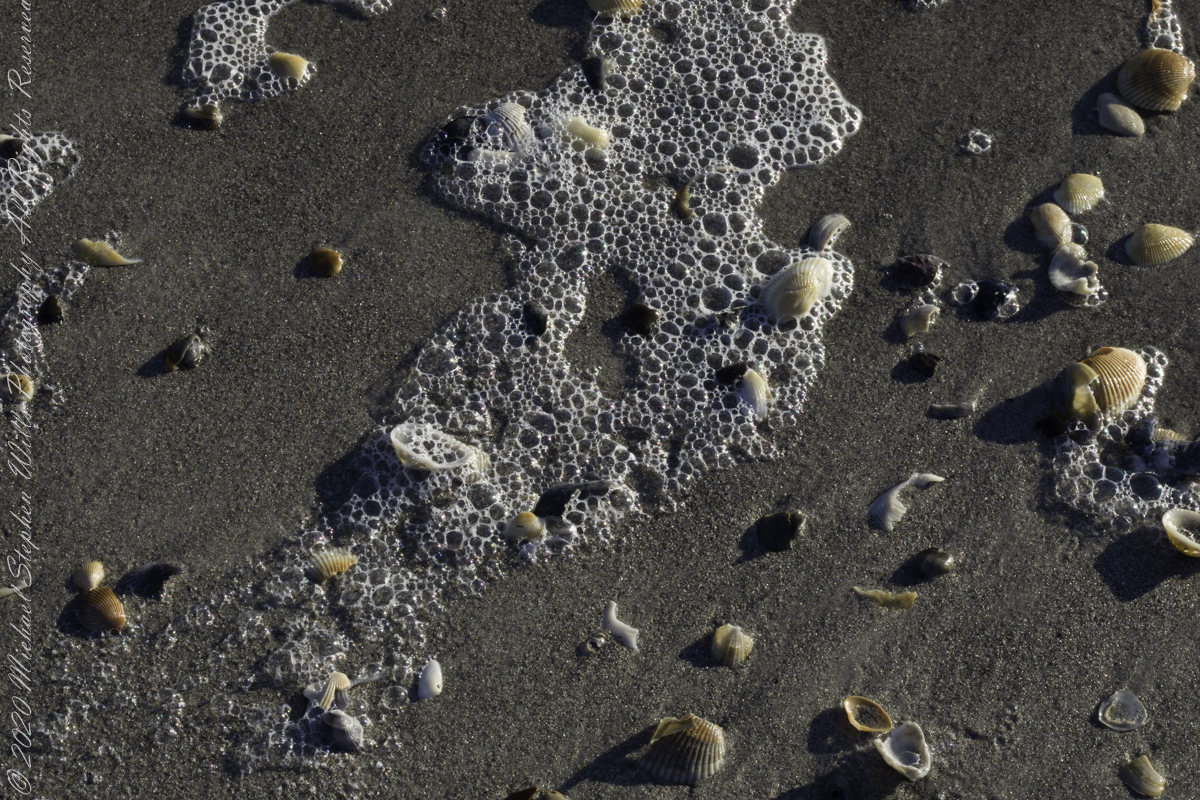

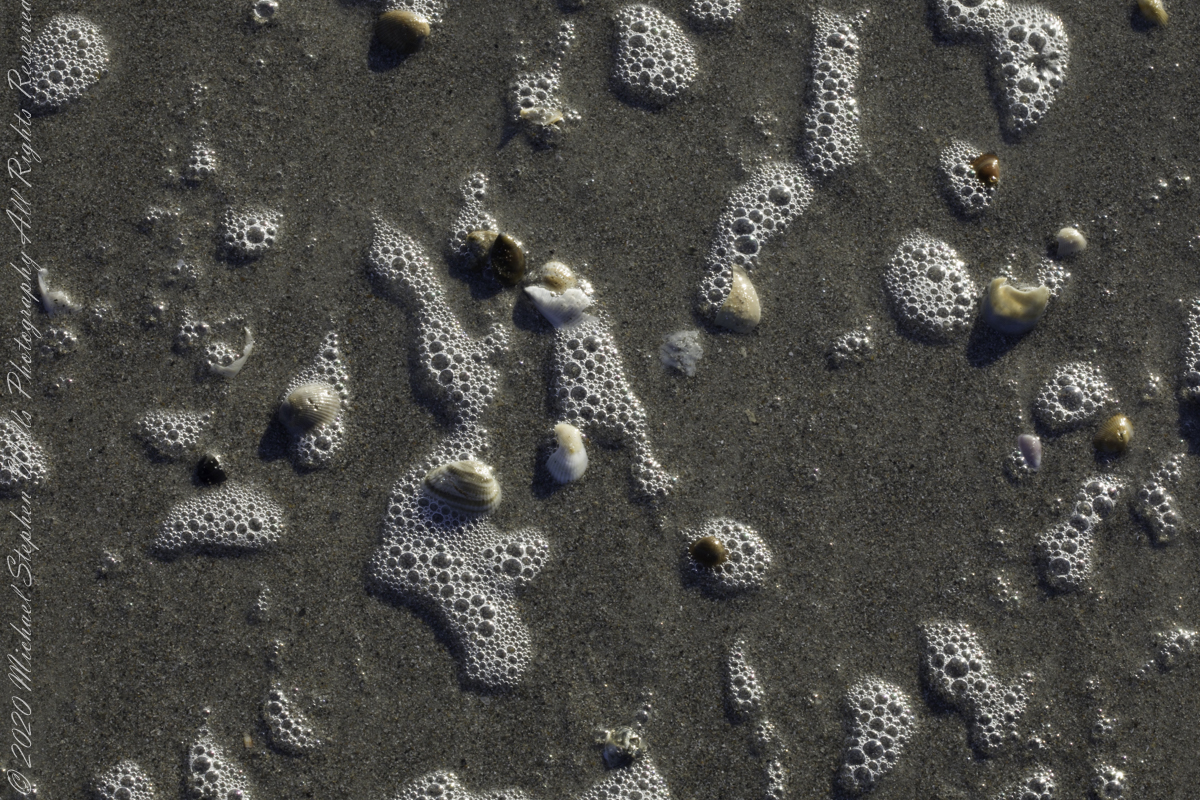

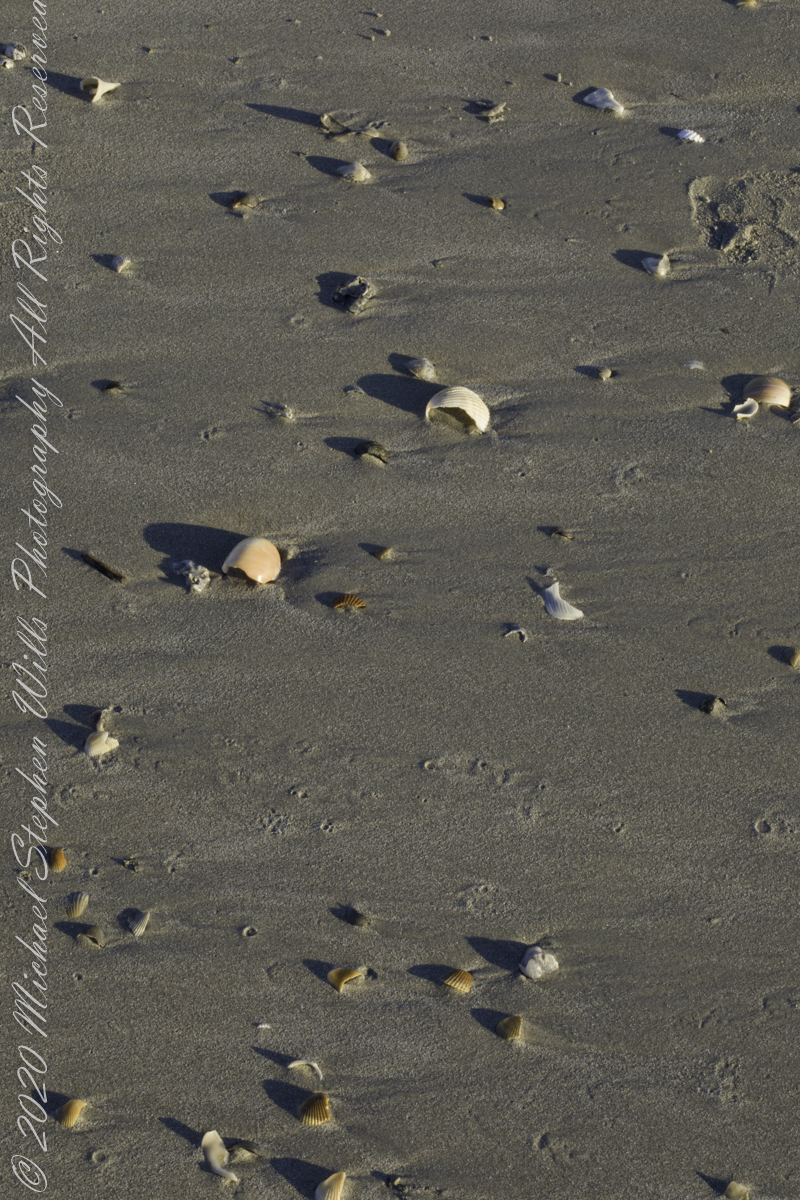

As I wander along the coast, the variety of seashells scattered across the beach fascinates me, particularly the whelk shells with their intricate designs and robust structure. This marvel of nature prompts me to delve into the science behind the formation of these shells, which are not just homes for the marine creatures but also a testament to the extraordinary processes that take place both within the organisms and across the cosmos.

The Architect: The Mantle of the Whelk

The journey of a whelk shell begins within the mollusk itself, specifically with an organ called the mantle. This organ is a marvel of biological engineering, responsible for laying down the calcium that forms the shell’s backbone. It secretes a matrix, a kind of biological scaffolding composed of proteins and polysaccharides, and then directs the deposition of calcium carbonate within this matrix to create the hard shell. The mantle’s work is meticulous, ensuring the shell’s growth and repair throughout the whelk’s lifetime.

The Building Blocks: Calcium, Carbon, and Oxygen

So why do the elements calcium, carbon, and oxygen play such a crucial role in shell formation? It’s a question of availability and suitability. These elements are abundant in the marine environment—calcium dissolved in seawater, carbon, and oxygen from both water and air. Their chemical properties allow the formation of calcium carbonate, a stable compound that can adopt various forms like calcite and aragonite, offering structural diversity for shells. Calcium carbonate’s moderate solubility enables mollusks to control shell formation precisely, and its biocompatibility ensures the process is safe for the living organism. Above all, the resulting crystalline structure provides immense strength and rigidity, a natural armor against predators and environmental challenges.

The Role of Calcium Carbonate

Calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) is not just a building block for shells; it’s a common substance that shapes our world. Found in rocks as calcite and aragonite, it forms limestone, the basis of pearls, and even the eggshells we encounter daily. This compound is an active player in both industrial applications and biological functions, serving as an agricultural amendment, a component in cement, and even a dietary supplement for humans.

The Mollusk’s Craft: Extracting from the Environment

Whelks are not alchemists; they do not create calcium carbonate from thin air. Instead, they are master extractors, pulling calcium and carbonate ions from their surroundings and depositing them as calcium carbonate to form their shells. The mantle is at the heart of this process, secreting proteins and enzymes to facilitate ion extraction from the water. The precise regulation of ion concentrations and pH ensures the calcium carbonate crystallizes in the desired form, perfectly tailored for the whelk’s protection.

Star-born Elements: The Cosmic Connection

It’s astounding to think that the elements composing whelk shells are not just earthly but cosmic in origin. The calcium (atomic number 20), carbon (atomic number 6), and oxygen (atomic number 8) that are so critical to these marine structures owe their abundance to the stars. The life cycles of stars, from their hydrogen (atomic number 1) and helium (atomic number 2) fueled births to the explosive supernovae and neutron star collisions that mark their deaths, generate and scatter these elements throughout the universe. These star-born materials eventually coalesced to form our solar system and Earth, providing the necessary ingredients for geological and biological phenomena, including the formation of the whelk shells I hold in my hand.

As I reflect on the shells before me, I am reminded of the interconnectedness of all things—from the inner workings of a tiny mollusk to the vast and violent furnaces of stars. These shells are not just remnants of life; they are cosmic artifacts, a reminder of our connection to the universe and the extraordinary processes that shape our existence.