The Newgrange façade and entrance of today is a creation from the large quantity of small stones unearthed and conserved during excavation given form by a steel-reinforced concrete retention wall.

The brilliant white quartz cobblestones were collected from the Wicklow Mountains, 31 miles to the south. Our guide called them “sunstones” for the way they reflect sunlight. In the following photograph is white quartz, the same excavated 1967-1975 from the Newgrange site and incorporated into the facade, I collected from “Miners Way” along R756 (above Glendalough).

You can also see in these photographs dark rounded granodiorite cobbles from the Mourne Mountains, 31 miles to the north. Dark gabbro cobbles from the Cooley Mountains and banded siltstone from the shore at Carlingford Lough both locations on the Cooley Peninsula where my mother’s family still has farms.

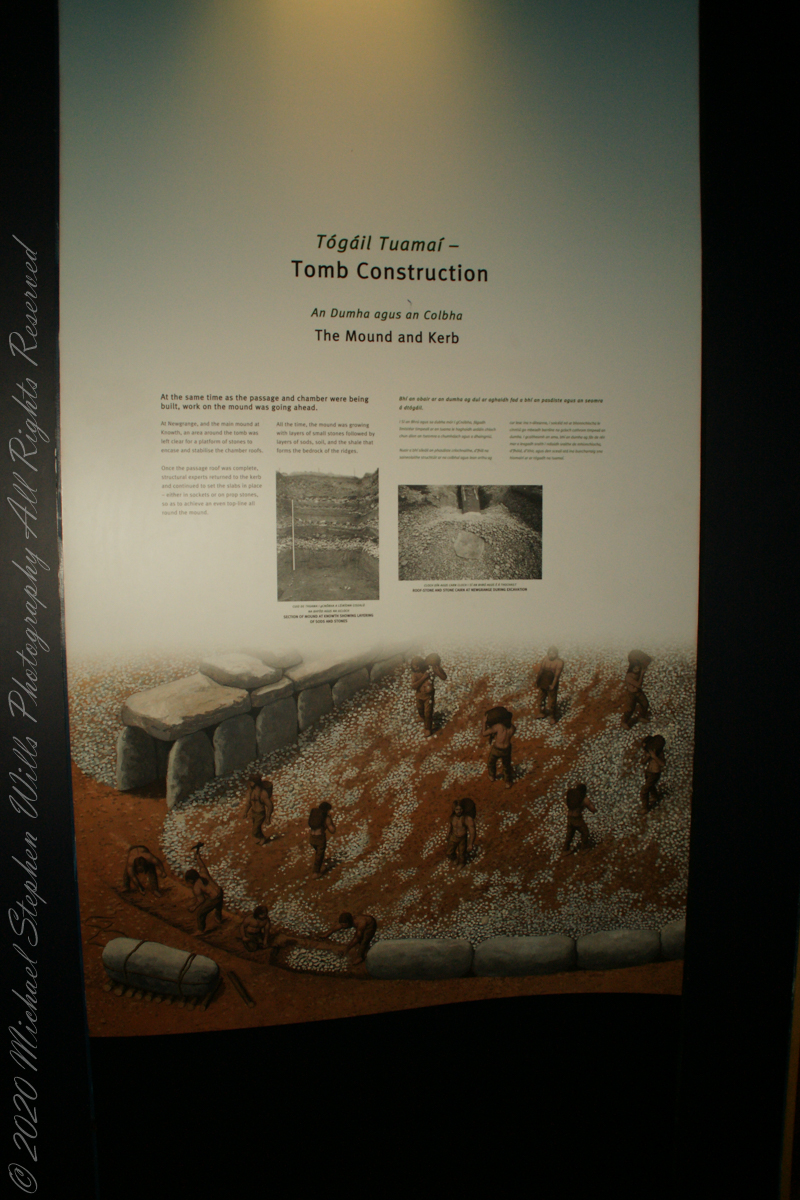

The stones may have been transported to Newgrange by sea and up the River Boyne by fastening them to the underside of boats at low tide. None of the structural slabs were quarried, for they show signs of having been weathered naturally, so they must have been collected and then transported, largely uphill, to the Newgrange site. The granite basins found inside the chambers also came from the Mournes.

Geological analysis indicates that the thousands of pebbles that make up the cairn, which together would have weighed about 200,000 tons, came from the nearby river terraces of the Boyne. There is a large pond in this area that is believed to be the site quarried for the pebbles by the builders of Newgrange.

Most of the 547 slabs that make up the inner passage, chambers, and the outer kerbstones are greywacke. Some or all of them may have been brought from sites either 3 miles away or from the rocky beach at Clogherhead, County Louth, about 12 miles to the northeast.

Click Me for the first post of this series.