The Louisa Duemling Meadows, nestled within the expansive embrace of Sapsucker Woods, offers a vibrant tableau of life, brimming with opportunities for exploration and a sense of wonder. This new trail, winding through golden fields and punctuated by bursts of wildflowers, whispers tales of the land’s natural and cultural heritage.

Louisa Duemling: A Steward of Nature

Louisa Duemling, the meadows’ namesake, was a dedicated conservationist and philanthropist who supported the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s mission to protect birds and their habitats. Her legacy lives on in these serene fields, where her commitment to preserving the environment is reflected in every thriving plant and songbird.

Black-eyed Susans: The Meadow’s Golden Treasure

Dominating this summertime landscape with their radiant yellow petals and dark central disks, Black-eyed Susans (Rudbeckia hirta) are a hallmark of the meadows. These cheerful blooms are a delight to the eye, a cornerstone of meadow ecosystems. As members of the Asteraceae family, their composite flowers serve as a rich nectar source for pollinators like bees and butterflies, ensuring the vibrancy of these fields.

Historically, Black-eyed Susans have been used in traditional medicine by Native American tribes for their putative anti-inflammatory properties. Their ability to thrive in diverse conditions also makes them a symbol of resilience and adaptability.

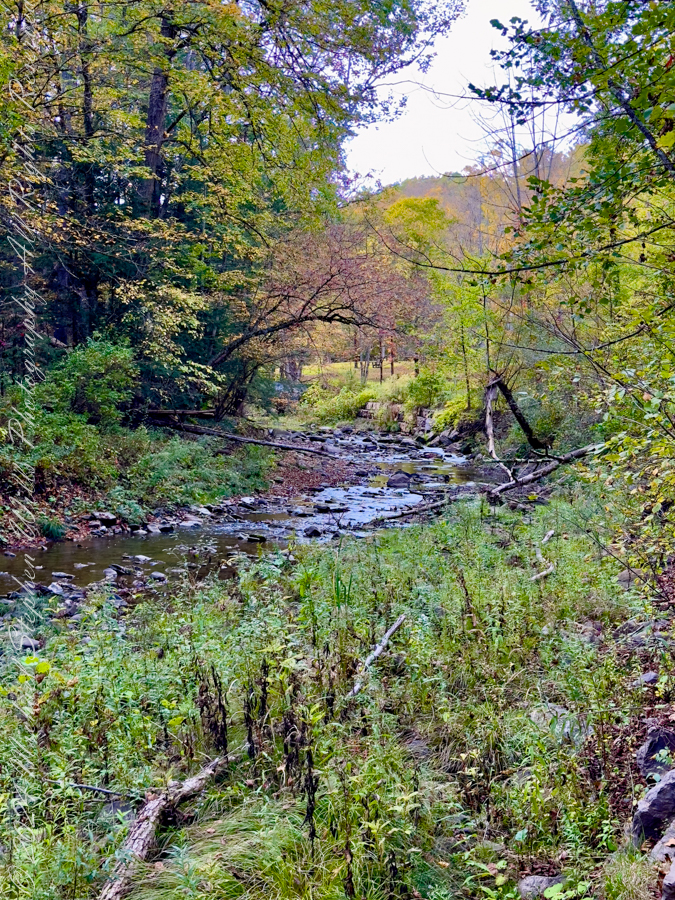

A Symphony of Green and Gold

Walking through the trail, one is greeted by the harmonious interplay of goldenrods (Solidago spp.), milkweeds (Asclepias spp.), and asters (Symphyotrichum spp.). Goldenrods, with their feathery clusters of yellow blooms, are often mistaken as allergenic culprits, though it is the inconspicuous ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia) that deserves this reputation. Milkweeds, with their milky sap and delicate pink or white flowers, are vital to monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus), serving as the sole food source for their larvae.

Among these botanical wonders, the birdhouse stands as a sentinel, a reminder of the intricate relationship between flora and fauna. These wooden structures provide safe havens for cavity-nesting birds like Eastern Bluebirds (Sialia sialis) and Tree Swallows (Tachycineta bicolor), fostering biodiversity within the meadow.

A Horizon Framed by Pines and Clouds

The open meadow trails, flanked by clusters of Eastern White Pines (Pinus strobus) and punctuated by the azure sky, invite reflection and renewal. This is a place where the human spirit can align with the rhythms of nature, where each step reveals new layers of beauty and discovery.

Embracing the Spirit of Discovery

To wander the Louisa Duemling Meadows is to immerse oneself in the timeless dance of life. The trail, carefully marked yet wild in essence, invites visitors to lose themselves in its beauty while finding solace in its quietude. This is not just a path through nature—it is a journey into the heart of conservation and a celebration of the life that thrives under Louisa Duemling’s enduring legacy.

As you leave the meadow, carry with you not just the memory of golden flowers and vibrant skies but the inspiration to cherish and protect the natural world. The Louisa Duemling Meadows are not only a gift to those who walk its trails but a reminder of the profound impact one can have in preserving our planet’s fragile beauty.