These photographs, made along the frozen margin of Cayuga Lake at Cass Park in mid-February 2026, carry a quiet paradox. The sky is a lucid blue, the light has that late-winter clarity that hints at spring, and yet the lake remains locked under a pale, glassy skin. A few geese stitch the air. A bench waits. Red and white beacons stand where water should be moving. The moment is fixed: late afternoon light in February, Finger Lakes winter—but the deeper story is written in physics, not pixels: why does lake ice linger so stubbornly during a thaw?

The short answer is that water is a hoarder of heat and ice is a keeper of promises. The long answer is the reason these scenes feel suspended between seasons.

Start with the cost of melting itself. Ice does not simply warm into water; it must first be converted, and that conversion demands a large, fixed payment of energy known as the latent heat of fusion. To melt just one kilogram of ice takes about 334,000 joules—and that energy raises the temperature not at all. It is spent entirely on changing solid to liquid.

Scale that up to a lake surface and the numbers become sobering. Even a modest sheet of ice—say ten centimeters thick—contains roughly ninety kilograms of ice per square meter. Melting that much requires on the order of thirty million joules per square meter. To put this in a human context, in 1 kcal there are 4,184 joules. Melting a square meter of ice requres 7,170 kilocalories (kcals) or 3.6 days for a person expending 2,000 kcals per day. Spread across square kilometers of lake, the energy bill climbs into the tens of terajoules. That is the hidden arithmetic behind the familiar disappointment of a February thaw: a few warm days feel dramatic to us, but to a lake they are only a small down payment.

This leads to the second, more subtle constraint: melting ice keeps itself cold. As long as ice is present, the surface of the lake is pinned near 0 °C (32 °F). Incoming heat does not make the surface warmer; it simply converts more ice into water at the same temperature. The thin layer of meltwater that forms on top is also near freezing, so the entire interface remains locked at winter’s threshold. There is no “warming momentum” here—no quick rise in temperature to accelerate the process. The system quietly consumes energy without changing its outward thermal expression.

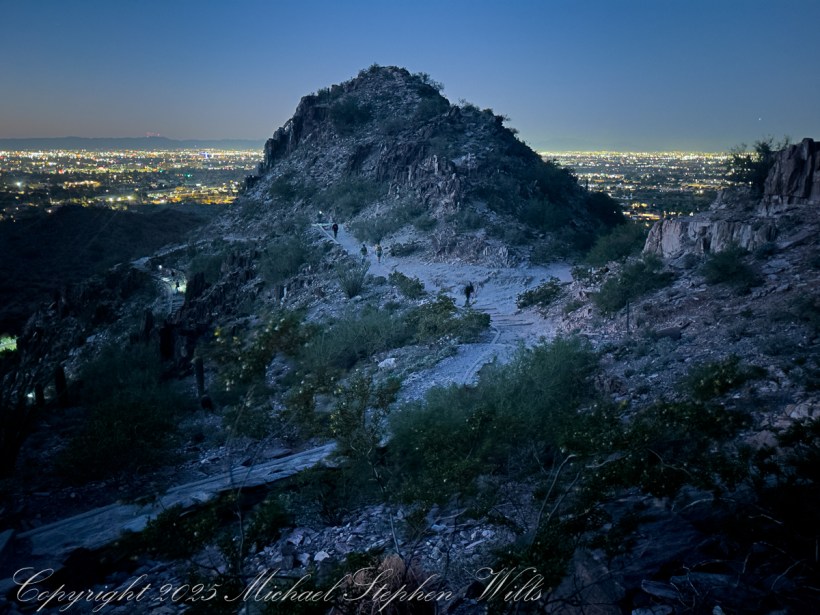

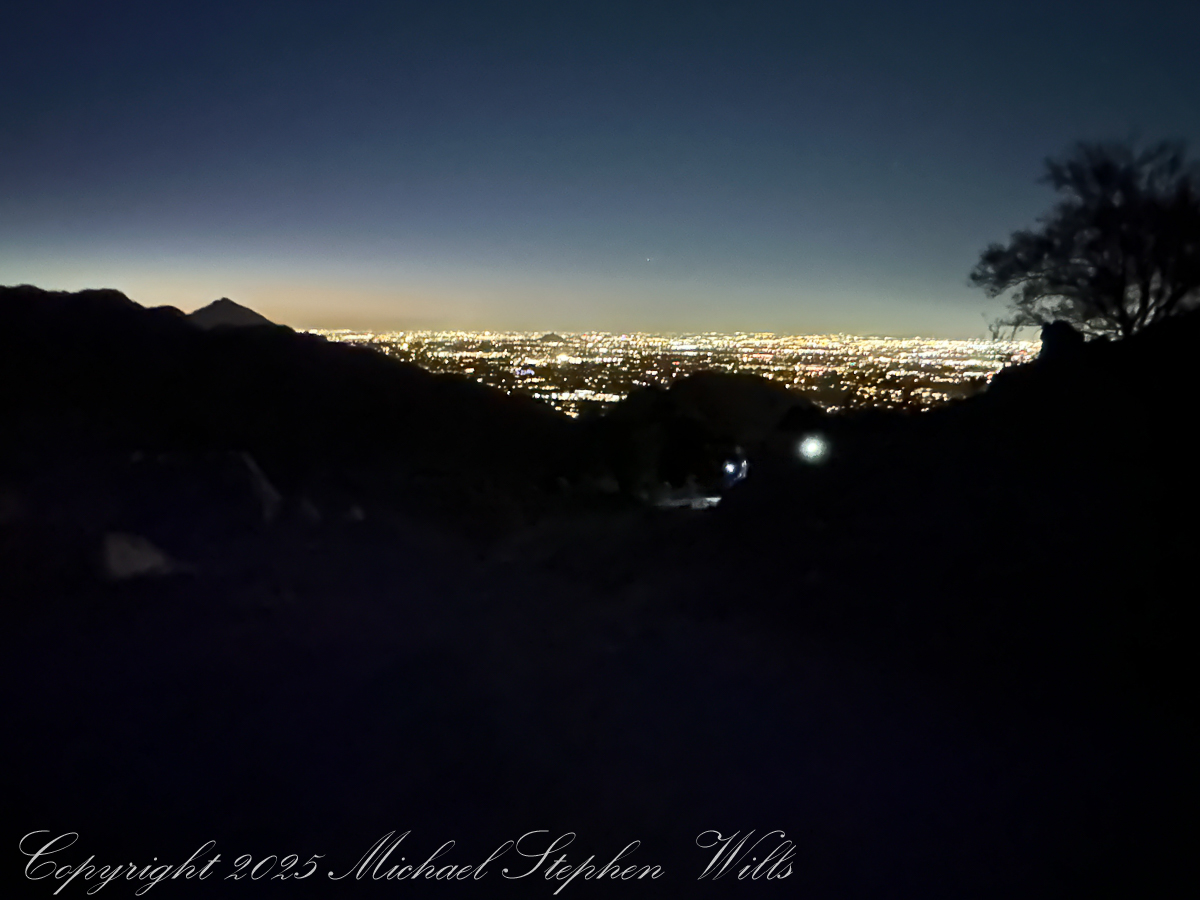

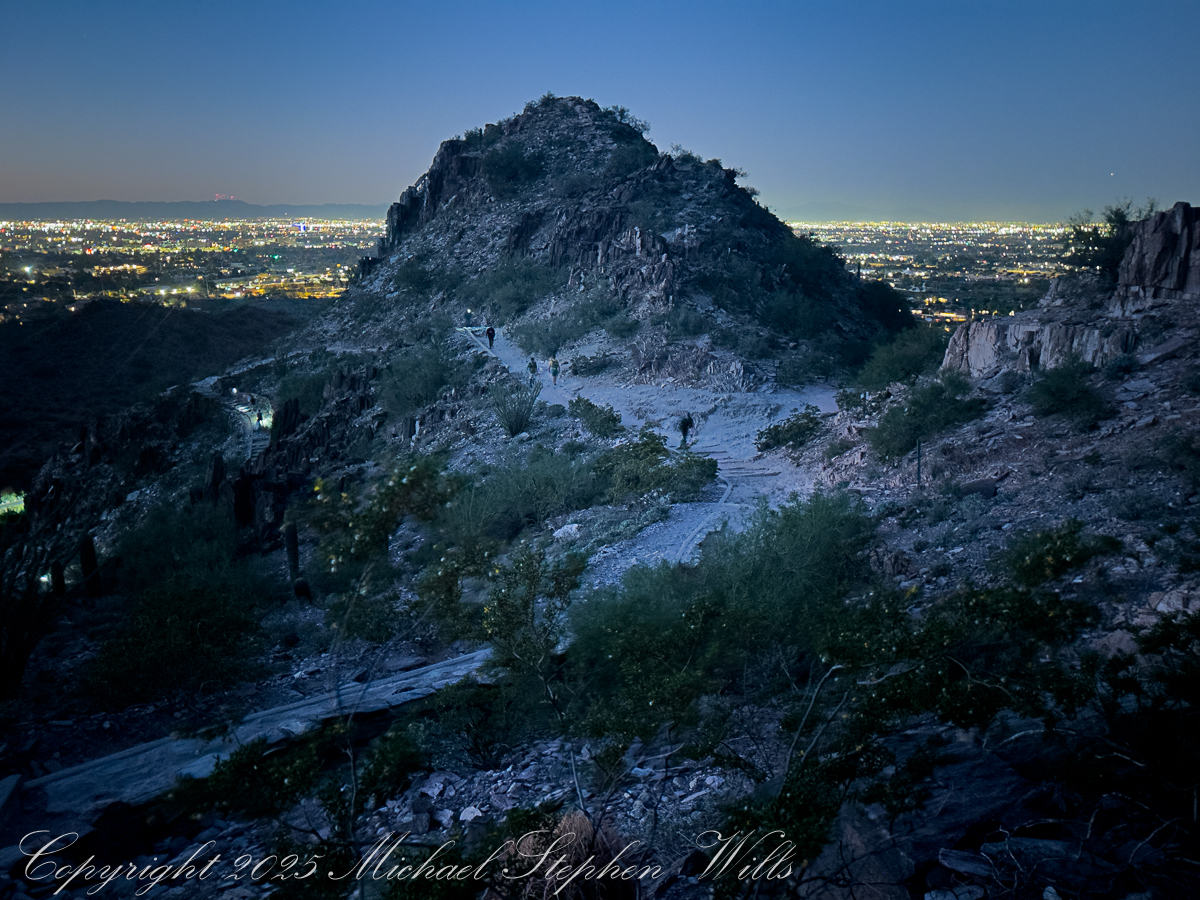

That is why the lake in these images can look bright and almost springlike while remaining physically winterbound. Sunlight is being spent on erasure, not on warming.

A third rule of water deepens the delay. Freshwater is densest not at freezing, but at about 4 °C (39 °F). In early spring conditions, the coldest water—near 0 °C—floats. The slightly warmer, denser water below tends to stay below. This creates a stable stratification: a cold, near-freezing surface layer sitting like a lid on the lake.

The consequence is crucial. The lake cannot easily mix warmer subsurface water upward to attack the ice from below. The thaw must work mainly from the top and the edges—where sunlight, mild air, rain, and shoreline heat can do their work—rather than through a coordinated, whole-lake turnover. In practical terms, the ice is dismantled by margins and seams, not by a sudden, uniform collapse.

Add to this the reflective nature of ice and snow. The pale surface in these photographs is not merely beautiful; it is also defensive. Bright ice and snow reflect a significant fraction of incoming sunlight back into the sky. Dark, open water would absorb that energy eagerly and warm quickly. As long as the lake remains light-toned, it is actively rejecting some of the very energy that could hasten its release.

Thickness and structure matter too. Winter does not lay down a single, simple sheet. It builds layers: clear black ice, milky refrozen crusts, snow-ice composites, trapped bubbles—each a page in winter’s ledger. A brief thaw may soften the surface, open a lead near shore, or trace fine cracks across the sheet, but the bulk remains. In the closer views—the lighthouse and the red beacon standing in frozen sheen—you can see subtle tonal shifts and faint stress lines, the calligraphy of slow change. These are signs of negotiation, not surrender.

Scale, finally, is destiny. Cayuga is long and deep; it behaves more like a small inland sea than a pond. Small waters can change their minds quickly. Large waters are conservative. They remember. The heat they lost in autumn must be repaid, carefully and in full, before winter loosens its hold. This is why harbors and shallows darken first, why the margins in these scenes show hints of movement while the center keeps its pale composure.

Put together, these rules explain the peculiar patience of February ice. The thaw is not a switch but an accounting. Enormous quantities of energy must be delivered just to accomplish the phase change. While that work is underway, the surface temperature barely moves. The cold meltwater stays on top, limiting mixing. The bright surface reflects sunlight. The lake, in effect, resists haste through the ordinary, unromantic laws of physics.

There is an austere beauty in this. Ice is a temporary architecture built by the loss of heat, and its demolition requires an equally disciplined repayment. The quiet in these images is the quiet of bookkeeping—joules being transferred, layers being undone, thresholds being approached but not yet crossed. When the change finally comes, it often feels sudden: a windy day that breaks the sheet into plates, a warm rain that darkens the surface, a week when the margins retreat visibly. But that drama is only the visible last act of a long, invisible exchange.

So the lake lingers. Not out of stubbornness, but out of fidelity to the rules that govern it. Under a sky that already looks like April, Cayuga is still paying winter’s invoice. The ice remains until the account is settled—and when it finally goes, the benches will no longer face a mirror of light, but a moving field of dark water, ready once again to begin the long work of storing heat for another year.