Moon Fin

Gibbous Moon and Red Rock

Gibbous Moon and Red Rock

Step into our visual journey across Canyon de Chelly’s ancient grandeur, where photographs capture Navajo families weaving through the immense narrative of sandstone and sky.

A native American village among the crowds

In 2003 and 2008, the author visited and photographed White House Ruin in Canyon de Chelly, observing changes in landscape.

In November 2003, my son Sean and I journeyed up Route 191 from Petrified Forest National Park, arriving in Chinle on a crisp autumn afternoon. My photography equipment at the time was modest: a Sony Point and Shoot 5 MP camera with filters, a purse-like over-the-shoulder bag, and a basic tripod from Kmart.

We reached the White House trailhead in Canyon de Chelly and began our hike. The trail was quiet, and as the sun set at 5:20 pm, we found ourselves virtually alone. A dense growth of Russian Olive trees dominated the wash at that time. In the dimming light, I captured a distant shot of the White House Ruin, whitewashed, set against the backdrop of autumn-hued Russian Olive foliage. Nearby, a grove of Cottonwoods, still green, stood near the canyon wall.

By the time Pam and I returned in July 2008, four years and nine months later, the landscape had changed. The invasive Russian Olives had been removed, and the White House Ruin was no longer painted white.

The same Route 191 that Sean and I had taken in 2003 led us through the Four Corners region of Northern Arizona. Pam and I had traveled from Colorado, arriving in the late afternoon. This time, the Navajo Reservation’s adherence to daylight savings time meant the sun wouldn’t set until 8:33 pm. My aim was to photograph the White House Ruin that I had missed years earlier.

That July day the sun set 8:33 pm as the Navajo Reservation observes daylight savings time. My goal was to photograph the White House Ruin I missed in 2003. We arrived at the trail head. My photography kit was expanded from 2003, now included a Kodak DSC Pro slr/C, the “C” meaning “Canon” lens mounting, a Sony 700 alpha slr (I only use a variable lens), Manfrotto tripod with hydrostatic ball head, and the backpack style Lowe camera case. With the tripod it is over 25 pounds.

With this on my back I was prepared to boogie down the trail. At the height of tourist season there were many more people at the trailhead. Pam, being a friendly person, started a conversation while I ploughed ahead along the flat canyon rim. It is solid red sandstone, beautiful, generally level with enough unevenness to require attention. When Pam saw how far ahead I was she tried to catch up, tripped, fell hard.

I backtracked to Pam and we decided what to do. She thought, maybe, the fall broke a rib. We decided to proceed and descended, slowly, together. Here we are in front of the ruin. The sun, low in the sky, is moving below the south canyon wall. This is a perfect time, and I used both cameras.

The sweep of cliff and desert varnish was my intent to capture. Here it is through the Canon 50 mm lens.

I captured this version with the Sony Alpha 700 slr, the variable lens set to widest angle.

Here the camera setup waits out the sun…..

1975 University of Arizona alumnus recounts annual homecoming trips and an encounter with a haunted ranch.

In my Homecoming Parade 2003, I described my initial reconnection with the University of Arizona (U of A) as a 1975 graduate and alumnus. This personal project of involvement with U of A and Arizona continued through 2011 with annual autumn trips to coincide with Homecoming. The travel was as a CALS (College of Agriculture and Life Sciences) Alumni Board of Directors member, a primary responsibility was raising funds for scholarships.

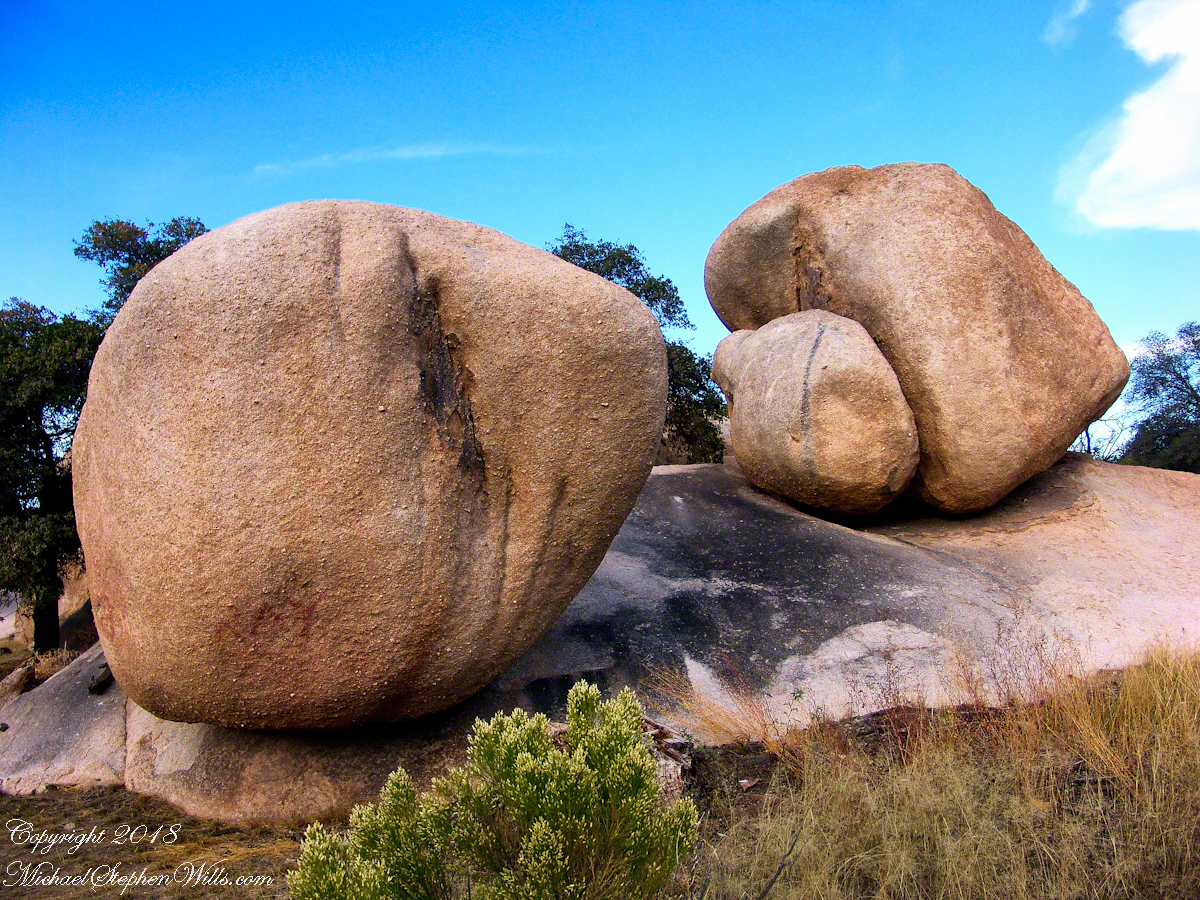

I met, Linda Kelly, the owner of the Triangle T Guest Ranch, while camping in the Chiricahua Mountains. I arrived a week before homecoming to photograph the landscape, nature and rock formations of the Chiricahua National Monument. Click this link for my Arizona Online gallery, including some work from that time. Linda and a friend were visiting that day and we struck up a conversation about the area and her Triangle T Guest ranch. The next day I was scheduled to guest lecture a class at the U of A, as an alumnus of CALS. The ranch was on the way and I needed a place to stay, so Linda gave me directions and I checked in.

She gave me a tour of the incredible weather granite rock formations of Texas Canyon and, meanwhile, shared stories of the history of Texas Canyon. It is appropriate for the Amerind Foundation to be here (see first photograph), the winter camp of an Apache tribe for generations.

That night, my request was for a room storied to be haunted by a spirit they call “Grandma,” as in when her footsteps wake you from a sound sleep you say, “It’s all right, Grandmother.” She woke me that night, footsteps in the dark, hollow on the wood floor, the room filled with a hard cold. I talked to her, without a response, while swinging my legs out of bed to reach the gas heater in the wall. I turned on the heat and the sound of expanding metal heat fins lulled me to sleep.

It made a good story for the students. They were surprised I could fall back asleep, but after all I had to be there the following morning.

I gave Linda a few of my photographs from that day and we made arrangements for the Triangle T to supply a two night package for the CALS “Dean’s Almost World Famous Burrito Breakfast” silent auction during 2008 homecoming.

crack of dawn

In this post we start the day of my posting “Family Trek“, July 19, 2008, when, well before the sun rose at 6:23 am Mountain Daylight Time (the Navajo Reservation observes daylight savings, the rest of Arizona does not), Pam and I were at the Spider Rock Overlook.

Most visitors to the canyon make use of a system of roads and parking lots next to strategic views. There is the White House Overlook we visited our first day, July 18, to hike from the trailhead into the canyon. There are also, on the south side of the canyon:

While getting ready I scoped out the location for interesting visual tropes. Utah Junipers are exceptionally hardy shrubs, stressed individual plants grow into compelling forms shaped by hardship. As the sun rose, this specimen emerged from the gloom and caught the first sun rays.

Enjoy!!

Happy April First “this post is no joke”

About 700 years ago, when the expansion of the Mongol empire was under way, on the other side of the planet people discovered a series of caves, formed in tuff, with a favorable location in a south facing cliff near water. Tuff, a rock formed from volcanic ash, is hard, brittle and soluble in water. From these properties this series of caves formed. The southern exposure provided excellent climate control for people, like those we now call the Salado, who understood how to exploit the location.

They constructed from local materials (mud, plants and rock) rooms in the upper cave just far enough inside to be warmed by the winter sun and protected during the summer when the sun’s sky-path was higher. Who knows how long the Salado lived in what must have been this paradise or why they left.

In March 2006, after returning from a nine-day backpack trip to the remote eastern Superstition Wilderness I used a four-wheel vehicle to reach the Roger’s Trough trailhead for a day trip to this site in Roger’s Canyon. The advantage of Roger’s Trough is the high elevation that leaves “just” about 1,100 feet of climbing (2,200 total) for the day. As it happens, it is downhill to the ruins though there is plenty of ups and downs plus scrambling over rocks.

I started late morning and a returning party met me on the way out and warned against leaving packs unattended. It seems they were victimized by pack rats. My timing was lucky and I had the site to myself.

First (refer to the “Roger Canyon” photograph, above) I climbed the cliff opposite from the ruins to set up a tripod an telephoto lens to shoot through the trees to capture the main building inside that very interesting looking tuff (see below). That central column (to the right) divides the cave opening and there are views from inside, up and across the canyon. In season, the cliffs are occupied by nesting birds and, higher up, there are fascinating caves in locations too high and steep to reach without the proper equipment.

As it is, climbing into the upper cave requires an exposed rock scramble. By “exposed” I mean the climber is exposed to falling. That is an intact wooden lintel of the visible structure opening and the larger structure, to the right, has curved walls.

I then explored in and around the site. The location of a lower cave made it useful for storage, it was walled off and the sturdy structure still stands today. By the way, I inverted this view for artistic purposes.

A lower cave is opened and accessible. Looking out, I felt the original inhabitants were with me and then a raven started calling over and over and over.

I was so fascinated by the possibilities of the site that time got away from me until this incessant cawing of a raven made me notice the lengthening cliff shadows. Here is a view (see below) of my way home, back up Rogers Canyon. My last shot before packing up. It took just over two hours to get out, at a steady pace. It was twilight as I approached the Rogers Trough trail head.

By the way, my posting before this one (“Finding Circlestone”) includes a shot of White Mountain. In that view, these ruins are on the other side of White Mountain.

Ancient Ruins

I first learned about Circlestone from stories The Searcher told during my first backpack into the eastern Superstition Mountains, on the Tule trail, April 2005. I described this in “Riding from Pine Creek to the Reavis Valley” where the Searcher described a stone circle, overgrown with Alligator Juniper, on the slopes of Mound Mountain. He pointed south toward a peak and foothills that rose from the valley floor and said, “follow the fire trail east from the southern Reavis Ranch valley.” There were strange happenings associated with Circlestone (as he called it) and he’d never taken the time to go there. “There is a book full of stories.” I eventually sought out Circlestone on the web and in books, but after I found it on my own using only the Searcher’s directions and advice from friends met on the way.

In 2006 I explored Circlestone twice along with my sister, Diane, who accompanied me. First for nine days early March 2006 using the Reavis Ranch trail from the north and the second for five days in November 2006, coming us the same trail from the south. Our first trip was Diane’s first “real” backpack adventure and we took it slow with a camp at Castle Dome where there are flat areas and exceptional views. Above, is the sunset from our second night (I camped the first night next to the car…we took it very, very sloooowwww).

Then, there was morning of our third day. Here is the Four Peaks Wilderness in the first rays of dawn. These are green, rolling foothills of grass, low shrubs and a few juniper. If you know where to look, there’s an unmarked trail to Reavis Falls (the highest waterfall in Arizona). I found the trail and visited the falls on a later trip.

After enjoying the Four Peaks, you turn around and see Castle Dome in the morning light, as in this photograph. Remember the same of the “dome”, because it is visible from the ultimate view from Circlestone.

Our camp was in the Reavis Valley, one of the first sites along the creek coming from the north. There were fantastic rock formations across the creek. Not far from there, the land falls away into steepness and then Reavis Falls. The Searcher told me about going that way, once. There is no trail down to the falls overlook and deep canyon carved by the water.

This photograph, above, is from a lovely forest of pinyon trees that grow along the trail to Circlestone (described by the Searcher as rising from the southern Reavis Valley). You can see the valley, just to the right, and a longer and steeper valley that rises from it up to White Mountain. That way is the southern legs of Reavis Trail. I have a movie clip from this same spot of the pinyons moving in the breeze and may post it at a later time.

All of the trail to Circlestone is a climb. You pass over “Whiskey Spring”, named for a still kept there in the 1800’s and over a steep defile gouged from the rock. The trail is well marked and I am told that, sometimes, there is no cairn marking the trail to Circlestone. If you are desperate to get there, look-up some excellent hiking directions available on the web. I have even found the circle on GoogleEarth, since I know where to look. If you like a challenge and the adventure, go from the directions the Searcher gave me.

From the fire line trail, the unmarked branch to Circlestone climbs steeply and follows a ridge through Alligator juniper, punctuated by stalks of century plant, to a broad way that rises to Circlestone as though to a monument overgrown by the same juniper.

There was an unusual experience on our first trip, on this portion of the trail. We were winding through the Juniper and, as it happened, Diane fell behind. After awhile I missed her and waited and, after a minute, went back to look for her. I found Diane sobbing uncontrollably, deep in grief over our father who passed away eleven years before. We talked about it until she felt better. She said it was as though a door opened and she could feel out father. What makes this exceptional is Diane is not given to anything like this and I ascribe her deep grief to the nature of the site. It is a mystery to this day.

At Circlestone, that first trip, we explored and experienced the site. You cannot see the entire wall at any point and need to wander through and over it, being careful not to disturb anything. Here and there, in the outer wall, are openings like the one in this photograph.

I call it a site hole because, on your knees, it is possible to look through and see the distant view through the trees. As you can see, the stones are a striking red color with green lichen growing thick.

On the second trip in November, knowing the way and having great weather, I brought my cameras to capture the exceptional views, one of which is above. I’d dearly love to come back to camp just below the ruin and do some work in the evening and morning light. For now, I can enjoy those views from Castle Dome.

Can you see the dome in the middle distance. I did a portrait of three horsemen who road up to Circlestone in November. We came to know them pretty well, that afternoon and the following morning down in the valley.

I carted up a tripod, so you can see Diane and I in the same spot.

Climb the Ladder

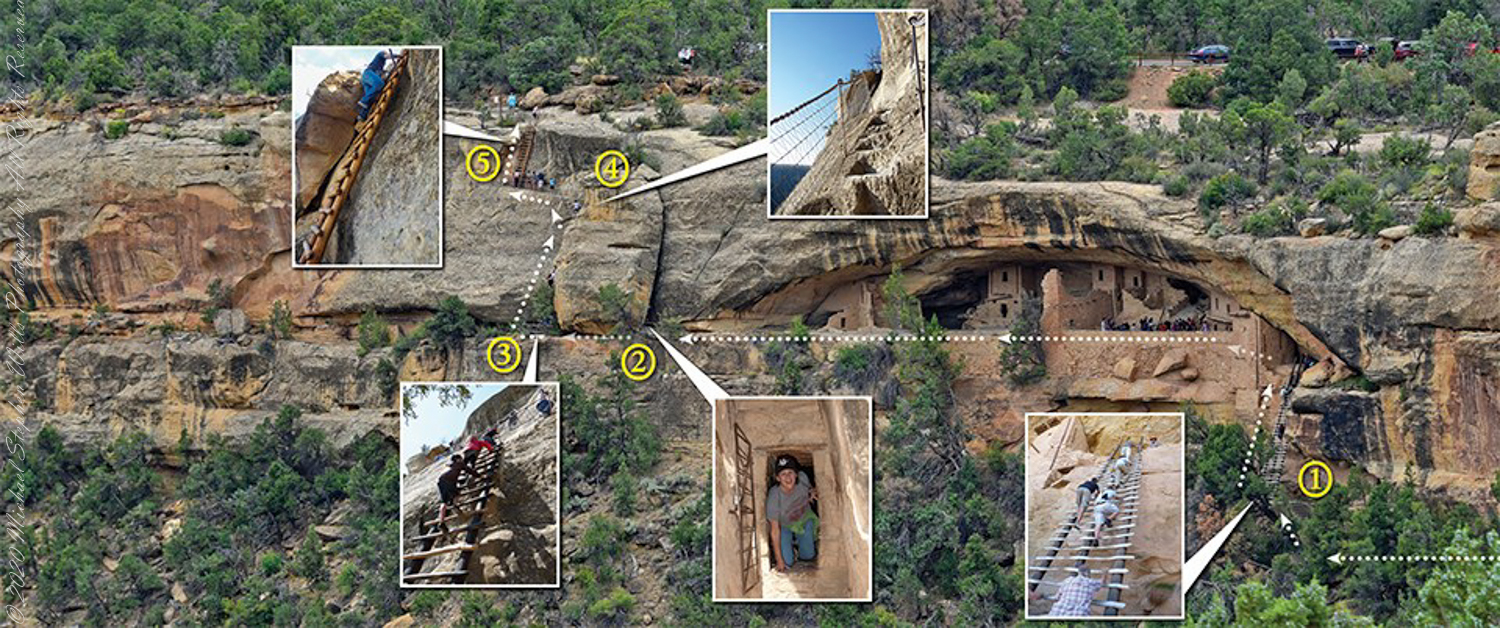

A visit to Balcony House is a 0.25-mile (0.4 km) hike. The tour requires walking down a 130-step metal staircase then, (1) climbing up one 32-foot (9.8 m) ladder to enter, two small ladders, and 12 uneven stone steps within the site.

(2) crawling through an 18-inch wide (46 cm) by 12-foot (3.7 m) long tunnel as you leave the site.

(3 – 5) ascending a 60-foot (18 m) open cliff face with uneven stone steps and two 17-foot (5 m) ladders to exit. Mesa Verde National Park, near Cortez, Montezuma County, Colorado.

We purchased our timed tour ticket at the visitor center at the foot of the Mesa, essentially a flat top mountain rising dramatically from the surrounding plain. In the second photograph we are looking over the mesa rim overlooking Soda Canyon.

The tour is a small adventure, starting with a climb down into Soda Canyon and a climb up a 32 foot ladder. The ladder is solid and we had plenty of time to climb with one person ascending at a time. I was a bit overwhelmed by the experience and had my equipment tucked away for safety. I had to leave my sturdy tripod in the car. A more adventurous photographer captured the following ladder photograph.

Here we are looking back to the entrance, where visitors crawl on hands and knees to enter.

Here is Pam twenty two (22) minutes into the tour. The structures are build into a naturally occurring cleft in the mesa cliff, below the rock shelf of the mesa top. The rock shelf is the roof above Pam.

Looking up to the ceiling above a rock and mud wall. The structures have been carefully, lovingly, conserved since the rediscovery of Mesa Verde in 1884. The conservation work began 1910.

The 38 rooms and two kivas house up to 30 people. The cliff northeast facing cliff provided little warmth from the sun in winter. At 7,000 feet and 37 degrees latitude, the mesa is cold wintertime — the average low being 18 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 8 Celsius). As other locations offer a southern exposure, the warmest side for the northern hemisphere, why was this site chosen by the ancients? The answer is found in the two water seeps emerging from the ground at the juncture geological layers where the water gathers and finds a way from surface rainfalls. The high desert climate here was dry then and now.

The walls demonstrate an enormous variety around basic patterns.

I had enough time to capture these “fine art” views of Balcony House, looking back toward the entrance. The round, in-ground structures are kivas, ceremonial and communal gathering spaces.

Possibly the most adventurous and potentially frightening tour component was the end, crawling on hands and knees along an 18 inch wide (46 centimeters) 12 foot long (3.7 meters) tunnel followed by a climb up a 60 foot (20 meters) open (exposed to falling over) cliff face.

Building Techniques

When the ancestral Puebloans moved from living next to their fields, in adobe structures, to these cliff dwellings, their building techniques were left behind.

Mud mortar was used to bind stones. Wood poles were used for to construct floors. These are walls captured during the Ranger guided tour of Balcony House.

This flat Kiva floor was achieved through clay, softened with water, formed and allowed to dry.

In this wall the poles rotted and crumbled, leaving behind these characteristic holes.

These architects excelled with adapting to the materials at hand.

The walls demonstrate an enormous variety around basic patterns.