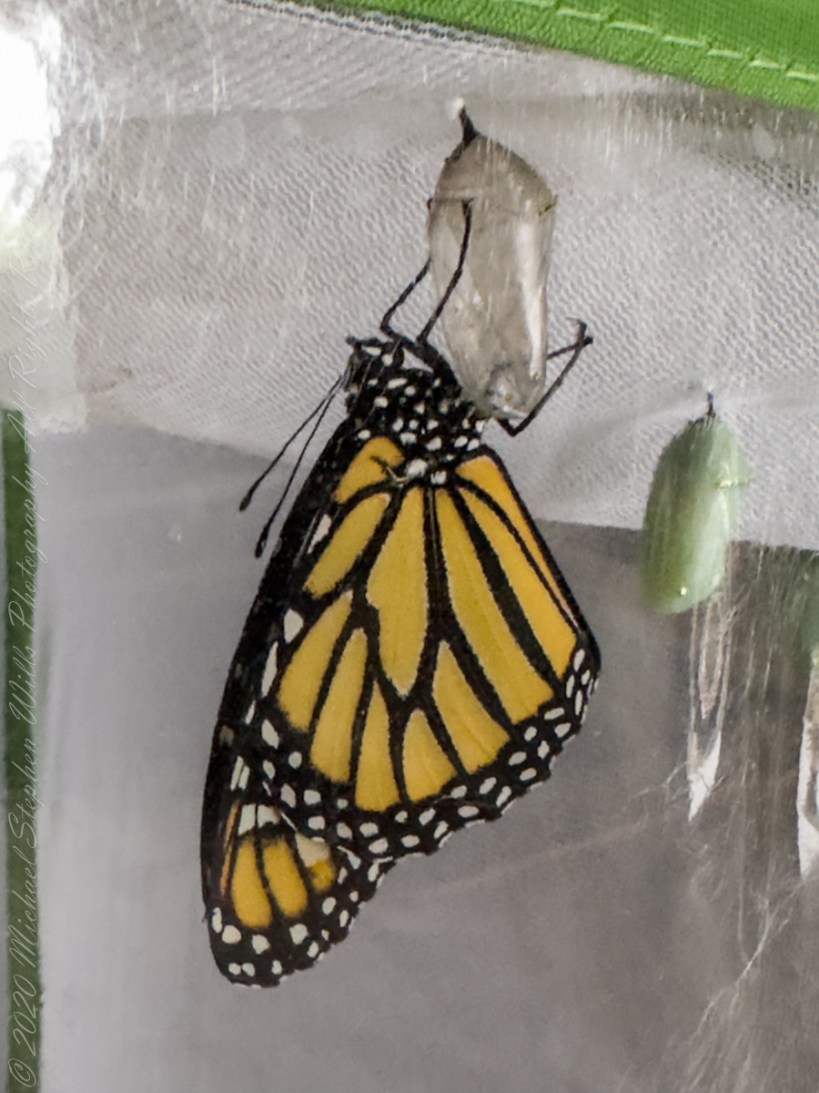

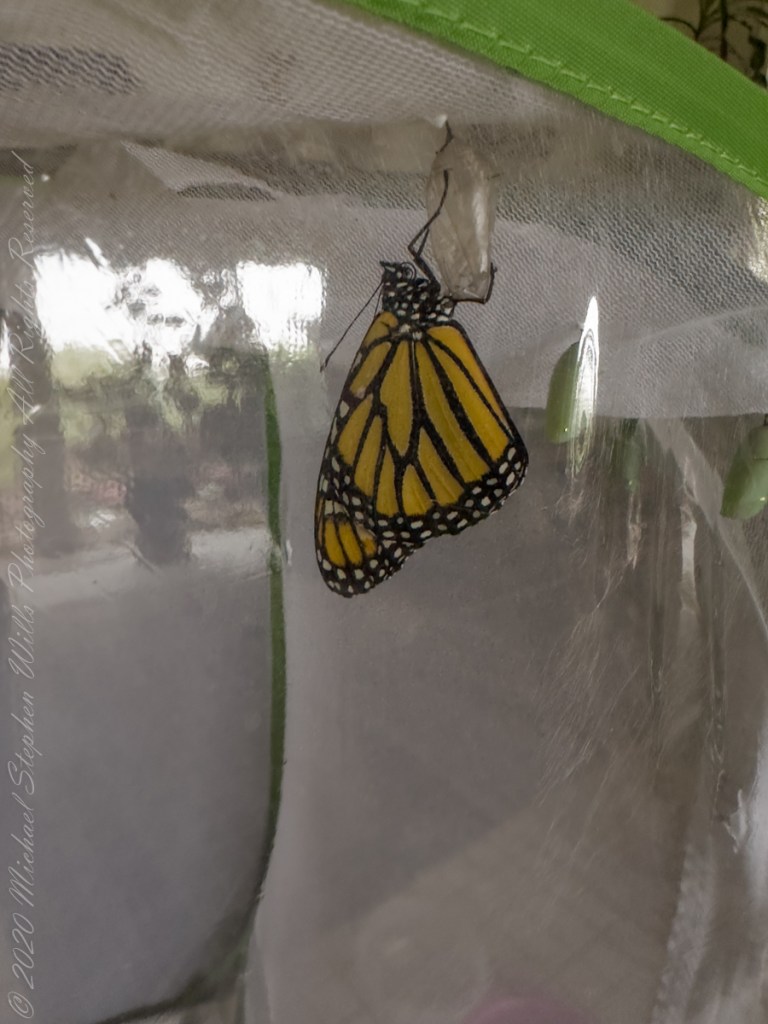

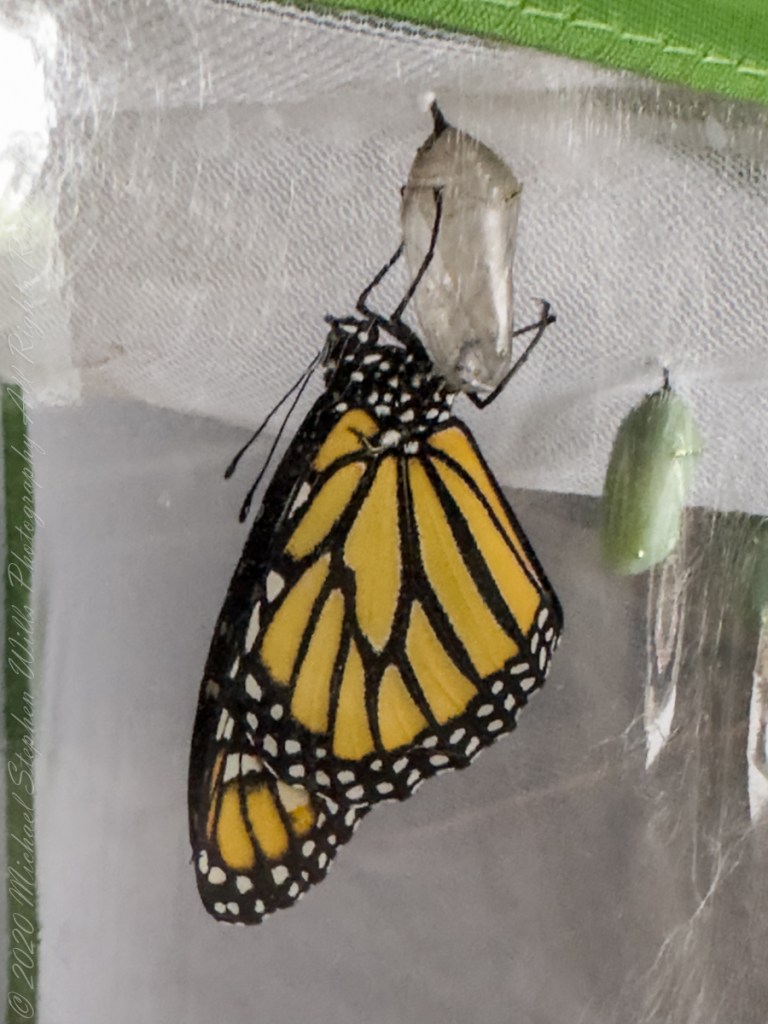

Our grandchildren spent the day with us, the last week of their summer before school begins. This July I had improved on my Monarch collection from 2022, when 9 butterflies were released, by two (2) caterpillars for a total of eleven (11) raised over several weeks to the chrysalis stage. When leaving to pick up the children for an outing one chrysalis skin had turned clear, a sign the enclosed butterfly is close to emerging. We returned from an outing for lunch to find this chrysalis unopened, so we checked now and then for progress. Four hours later, just as their Mom arrived for them, the grandchildren and everyone witnessed this event. What luck!!

“Migrating monarchs soar at heights of up to 1,200 feet. As sunlight hits those wings, it heats them up, but unevenly. Black areas get hotter, while white areas stay cooler. The scientists believe that when these forces are alternated, as they are with a monarch’s white spots set against black bands on the wings’ edges, it seems to create micro-vortices of air that reduce drag—making flight more efficient.”

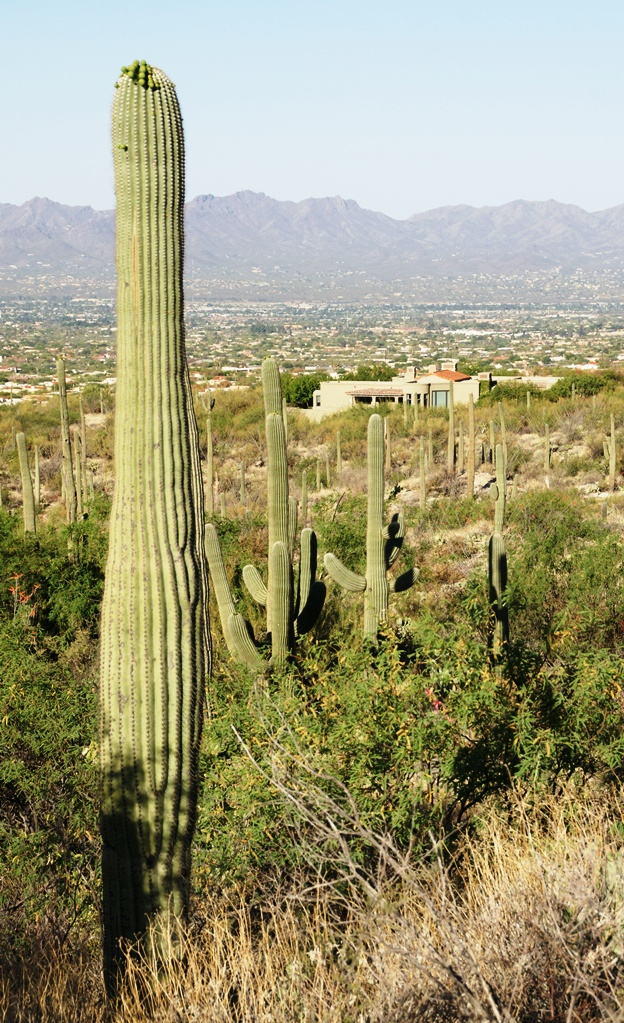

“Monarchs begin leaving the northern US and Canada in mid-August. They usually fly for 4-6 hours during the day, coming down from the skies to feed in the afternoon and then find roosting sites for the night. Monarchs cannot fly unless their flight muscles reach 55ºF. On a sunny day, these muscles in their thorax can warm to above air temperature when they bask (the black scales on their bodies help absorb heat), so they can actually fly if it is 50ºF and sunny. But on a cloudy day, they generally don’t fly if it is below 60ºF.“

“Migrating monarchs use a combination of powered flight and gliding flight, maximizing gliding flight to conserve energy and reduce wear and tear on flight muscles. Monarchs can glide forward 3-4 feet for every foot they drop in altitude. If they have favorable tail or quartering winds, monarchs can flap their wings once every 20-30 feet and maintain altitude. Monarchs are so light that they can easily be lifted by the rising air. But they are not weightless. In order to stay in the air, they must move forward while also staying within the thermal. They do this by moving in a circle. The rising air in the thermal carries them upward, and their overall movement ends up being an upward spiral. Monarchs spiral upwards in the thermal until they reach the limit/top of the thermal (where the rising air has cooled to the same temperature as the air around it). At that point, the monarch glides forward in a S/SW direction with the aid of the wind. It glides until it finds another thermal and rides that column of rising air upwards again.”

Reference: text in italics and quotes is from one of two online articles. “The monarch butterfly’s spots may be its superpower” National Geographic, June 2023 and “Fall Migration – How do they do it?” by Candy Sarikonda, September 2014.