They came north out of Chinle with the day already leaning west and the sun fallen low into the drag of horizon dust and the road ran flat and empty past rust hills and mesquite country until, turning into the sun at Mexican Water, after a long hour, at last they pulled into Kayenta where the streets lay quiet under the heavy sun and the windows of the store fronts cast their amber light out across the sand drifting across sidewalks and the wind stirred only faintly and then was still.

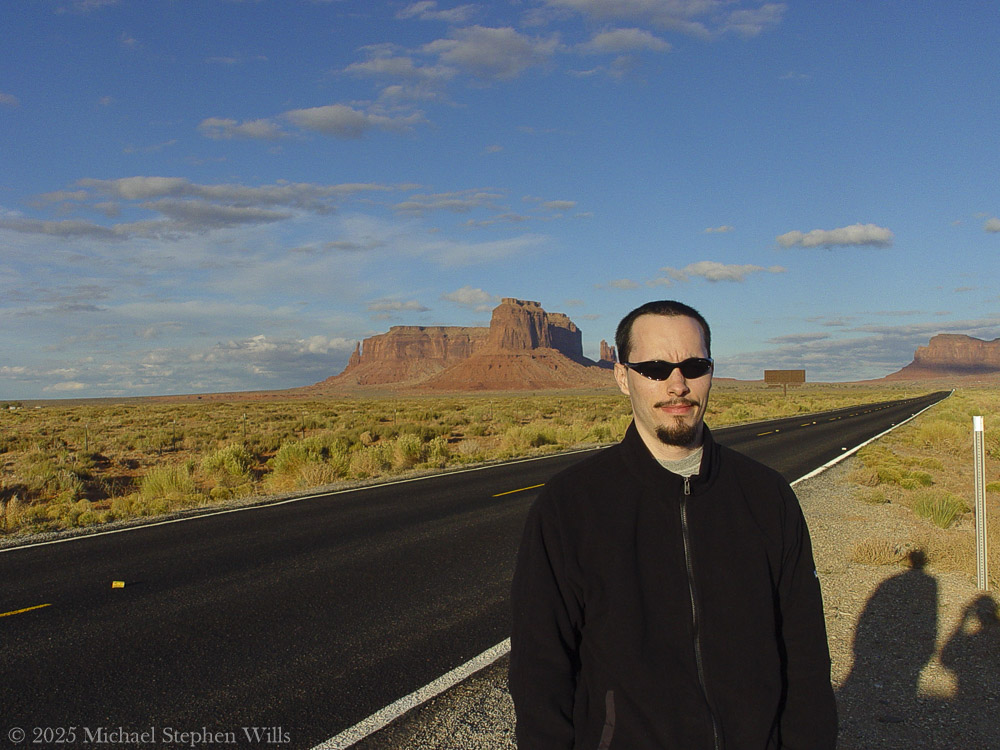

They left their bags in the room and turned north again without speaking. The son drove. A man, his father, sat quiet beside him and the sun slid low through the windshield and the sky was pale and cloudless and wide beyond reckoning.

The land began to rise and the road bent and climbed and fell again and then it came into view. Not slowly. Not like a curtain rising. It was simply there.

A shape in the far desert.

Like a ship that had grounded in a sea long vanished. A sheer mesa the color of blood and ochre and fire where the last of the day spilled westward and caught the rock face and made it burn.

He told the son to pull off. They stopped the car and got out and the sound of the engine fell away, the desert made no sound at all.

The man stood in the road and turned slowly. Eagle Mesa lay before him and the land stretched off in every direction and the fenceposts ran on into silence and the sky seemed to rest upon the buttes as if tired.

There were names for these places. Old names. Navajo names that spoke of eagles roosting and trees once there and water that came and went and did not come again. The mesa they called Wide Rock. The place where spirits go. He did not know the words but he knew the feeling.

The son came and stood beside him and did not speak. The man lifted the camera and took a photograph and then another. The road behind them shimmered with the last heat of day. He took another picture his son, dressed in black, his arms at rest and the red mesa rising behind him and the shadows of their bodies cast long across the gravel and the shoulder of the road.

They took turns with the camera. The son caught him midstride and smiling lit by sunlight, the land stretching out all around. A man small in a world not made for men.

There was no sound but the click of the shutter and the dry whisper of wind among the sage.

Later he would read that the rock was born of Organ Shale and De Chelly Sandstone and Moenkopi topped with Shinarump. He would know the spire they saw was first climbed by men named Beckey and Bjornstad and that it was called Tsé Łichii Dahazkani by those who’d named it before it ever had another name. He would know the mesa rose eleven hundred feet in less than a mile and that its runoff fed washes that fed rivers that fed nothing now.

But then he only stood and watched and knew it for what it was.

Not a monument to anything but time.

A stillness like prayer. A place that waits.

They lingered until the sun went and the sky turned iron blue and the shadows of the rock reached out across the valley floor and touched them where they stood. Then they climbed back in the car and drove south again and the road unwound behind them black and a single star above and the silence of the place held on inside them long after the valley was gone.