There are rocks that merely sit where gravity has placed them, and then there are rocks that arrive with stories already embedded—foreign syllables carried south on ice, dropped without explanation, and left for us to puzzle over. Glacial erratics belong to the second category. They are migrants with no passports, refugees of deep time, whose presence quietly contradicts the landscape that hosts them.

Long before anyone reached for a hand lens or an ice-flow diagram, people answered such contradictions with imagination. In Ireland, a boulder perched just so on a mountain side is not a geologic problem but a resting place. Leprechauns, we are told, favor such stones—high enough to observe human intrusion, solid enough to outlast it. Skepticism, as folklore reminds us, is not always a stable position. Kevin Woods—better known as McCoillte—found that out the hard way when doubt collided with experience on the slopes of Slieve Foye. What followed was not merely a conversion story, but an act of modern mythmaking: folklore translated into bureaucracy, imagination petitioning regulation, and “The Last Leprechauns” entering the unlikely language of conservation. Stone, story, and belief hardened together into something oddly durable.

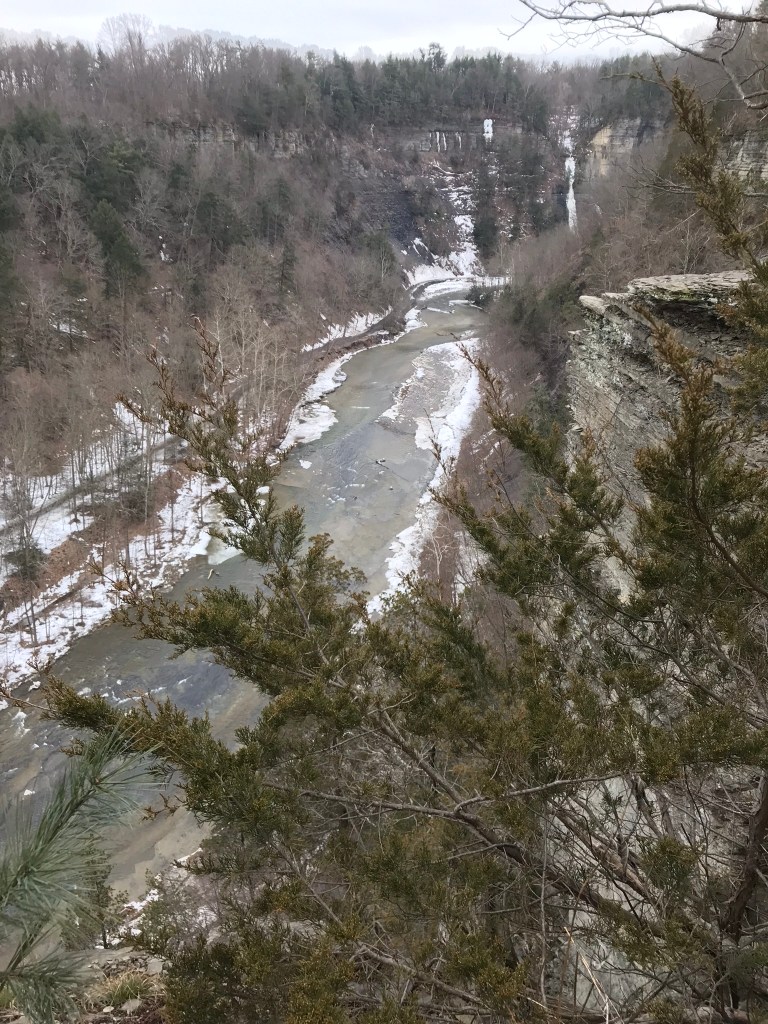

Back in the Finger Lakes, we tend to use a different grammar when confronted by an out-of-place rock. We name it, classify it, and trace its lineage northward. Erratics scattered across Tompkins County are geological sentences that begin somewhere else entirely. The bedrock beneath Ithaca—Devonian shale and sandstone—cannot account for crystalline intruders left behind like forgotten punctuation marks. These stones speak of ice sheets thick enough to erase valleys and decisive enough to transport mountains in fragments.

Some of those fragments have been domesticated. Cornell, for example, has never been shy about rearranging its stones. An unremarked erratic along the Allen Trail may once have been shrugged off as inconvenient rubble, while another—dragged from the Sixmile Creek valley—was carved into a seat and made eloquent. The Tarr memorial boulder, resting near McGraw Hall, transforms erratic stone into deliberate monument. It invites rest, contemplation, and perhaps gratitude for those who taught us how to read landscapes written by glaciers.

Elsewhere, erratics remain defiantly themselves. In winter, one along Fall Creek alternates between anonymity and revelation, depending on whether snow smooths its surface or retreats to expose lichen constellations. Bridges pass overhead, traffic flows, semesters turn over, yet the rock remains unimpressed. It has already endured pressure sufficient to rearrange its crystals; a passing academic calendar is not likely to trouble it.

Then there are the stones that confront us most directly—those we stumble upon in fields, pulled from soil by plow or frost, demanding explanation. A white, iron-stained marble boulder in a Tompkins County field is not subtle about its foreignness. It does not belong to the local vocabulary of shale and sandstone. Its pale surface, crystalline texture, and mineral scars point insistently north, toward the Grenville terrane of the Adirondack Lowlands. The Balmat–Edwards–Gouverneur marble belt offers the most persuasive origin story: metamorphosed carbonate rock carried south by Laurentide ice, released when climate and physics finally lost patience with one another.

What makes this particular erratic compelling is not just its provenance, but the improbability of its journey. Ice moved with purpose here, flowing south along bedrock valleys like Fall Creek and Cayuga troughs, turning the Finger Lakes region into a conveyor belt for distant geology. When the ice melted, it left behind evidence that refuses to blend in. Erratics are geological truth-tellers. They announce that this place was once unrecognizable, that what seems permanent is merely provisional.

Perhaps that is why folklore clings so naturally to stone. Whether leprechauns or Laurentide ice are credited, erratics insist on a larger frame of reference. They ask us to imagine landscapes in motion and beliefs under revision. A boulder can be a seat, a marker, a perch, or a puzzle—but never merely background. It waits, quietly confident, for us to catch up to its story.