In the Finger Lakes Region of Central New York State, a tapestry of flora unfurls across the landscape, marked by the vibrant yellows of woodland goldenrods. These wildflowers are not just a visual spectacle; they are integral to the ecosystem, contributing to its biodiversity and offering a feast for pollinators.

Woodland goldenrods (Solidago species) are part of a larger genus that encompasses over 100 species, many of which thrive in the varied habitats of the Finger Lakes. This region, with its rich soils, ample rainfall, and diverse topography, hosts an array of goldenrod species, each adapted to specific niches within the woodland understory.

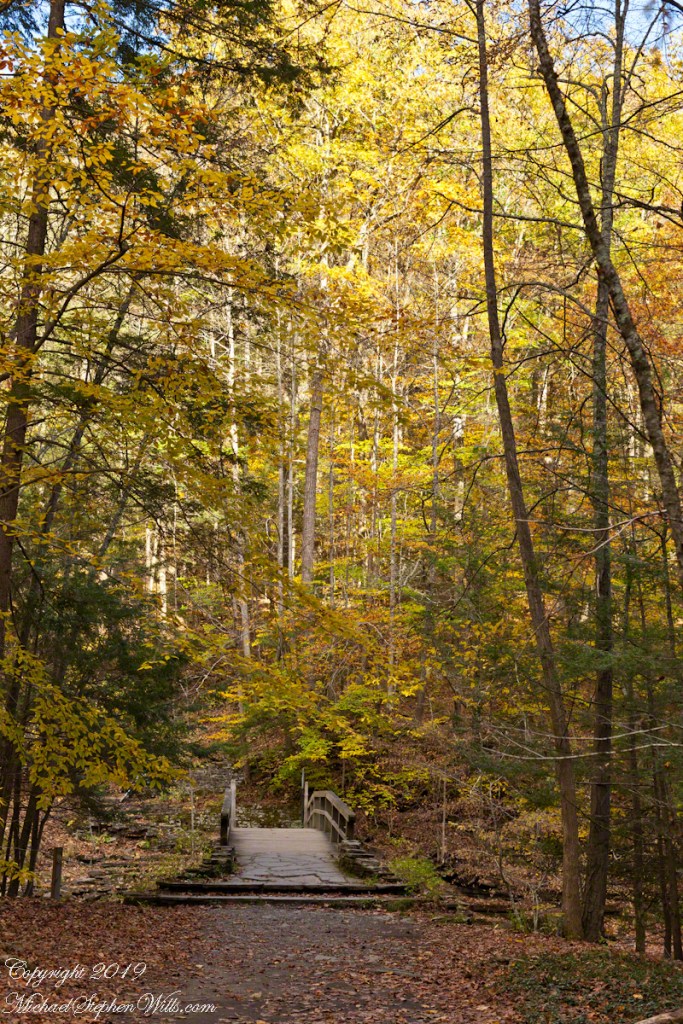

Hint: click image for larger view. Ctrl/+ to enlarge / Ctrl/- to reduce

Solidago caesia, commonly known as blue-stemmed or wreath goldenrod, is one species that graces these woods. Unlike the typical roadside goldenrods, this species thrives in the dappled shade, its delicate arching stems culminating in small bursts of yellow flowers that appear like beaded necklaces draped over the greenery.

Another species, Solidago flexicaulis, or zigzag goldenrod, earns its name from the characteristic bending pattern of its stem, which zigzags between leaf nodes. Its flowers are more clustered, favoring the shade and moist conditions of the forest floor. Its presence is often a sign of a healthy, undisturbed woodland.

Solidago odora, or anise-scented goldenrod, brings a sensory delight to the mix with leaves that emit a licorice-like fragrance when crushed. This goldenrod favors the edges of woodlands and clearings, where sunlight can reach its clusters of tiny, bright yellow flowers.

The downy goldenrod, Solidago puberula, is yet another species that decorates the region’s woodlands. It prefers dry, sandy soils, often found on the slopes and ridges that contour the Finger Lakes. Its name comes from the fine hairs that cover its stems and leaves, a characteristic that distinguishes it from its kin.

Each of these goldenrods plays a role in the woodland ecosystem. Their flowers provide nectar and pollen for a variety of insects, from bees and butterflies to beetles and flies. The seeds are a food source for birds, and the plants themselves offer habitat to numerous woodland creatures.

The presence of woodland goldenrods also indicates the health of the region’s forests. These plants are often pioneers in disturbed areas, contributing to soil stabilization and the natural succession process. They are resilient and adaptable, capable of surviving in a range of conditions from full sun to dense shade, though each species has its preference.

In the Finger Lakes Region, the goldenrods bloom from late summer into the fall, their golden hues a prelude to the coming autumnal display. They stand as a testament to the beauty and complexity of these woodlands, their very existence a reminder of the delicate balance within these ecosystems.

In conclusion, the woodland goldenrods of the Finger Lakes are more than just a splash of color in the verdant forests. They are a vital part of the ecological tapestry, contributing to the biodiversity and resilience of the region. Each species, with its unique adaptations and preferences, adds to the rich natural heritage of Central New York State, reminding us of the intricate web of life that thrives in these woodlands.

Click Me to view my photographs on Getty.