We arrived in Glendalough on a bright spring morning, a gentle breeze carrying the scent of grass and distant water. Even before stepping out of the car, I sensed something ancient in the air, as though the centuries themselves lay waiting among the stones. The peaks of the Wicklow Mountains rose around me, their slopes draped in verdant forests that whispered of forgotten tales. In the distance, shimmering like a secret, the Upper Lake beckoned under the watchful hush of rugged hillsides. I took a deep breath and started my wander.

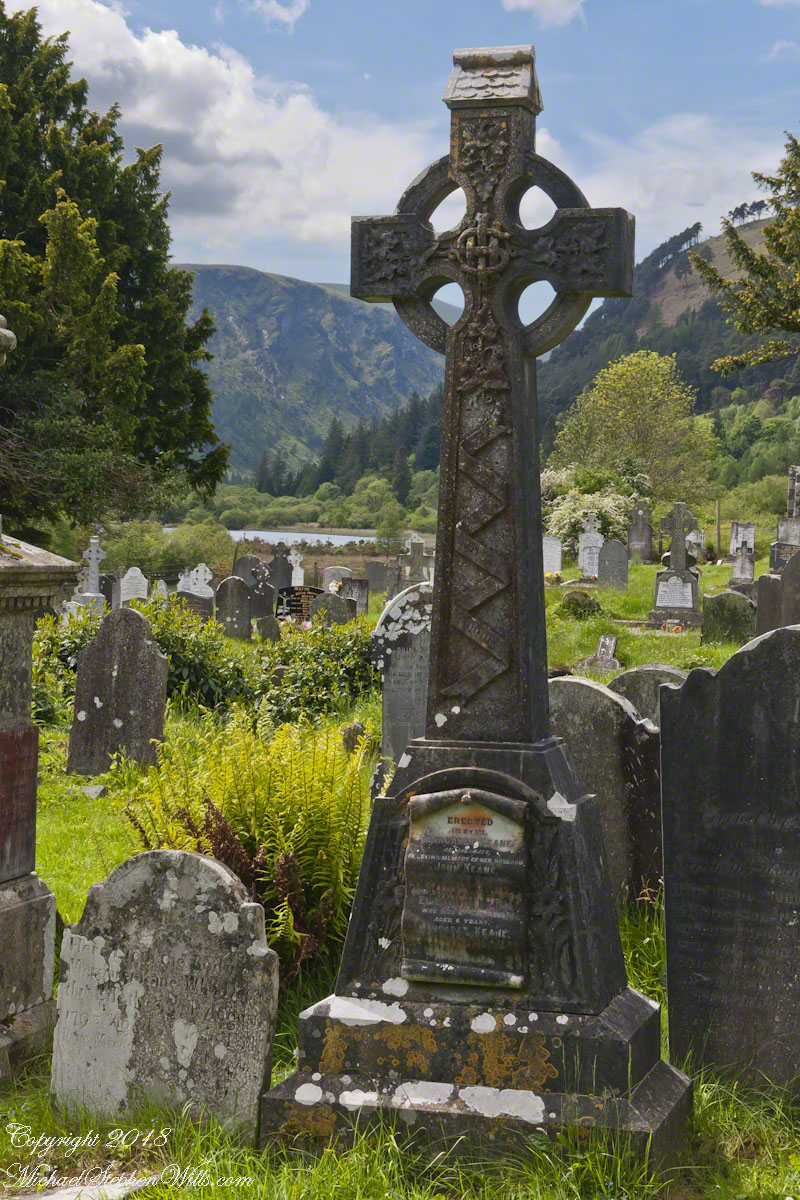

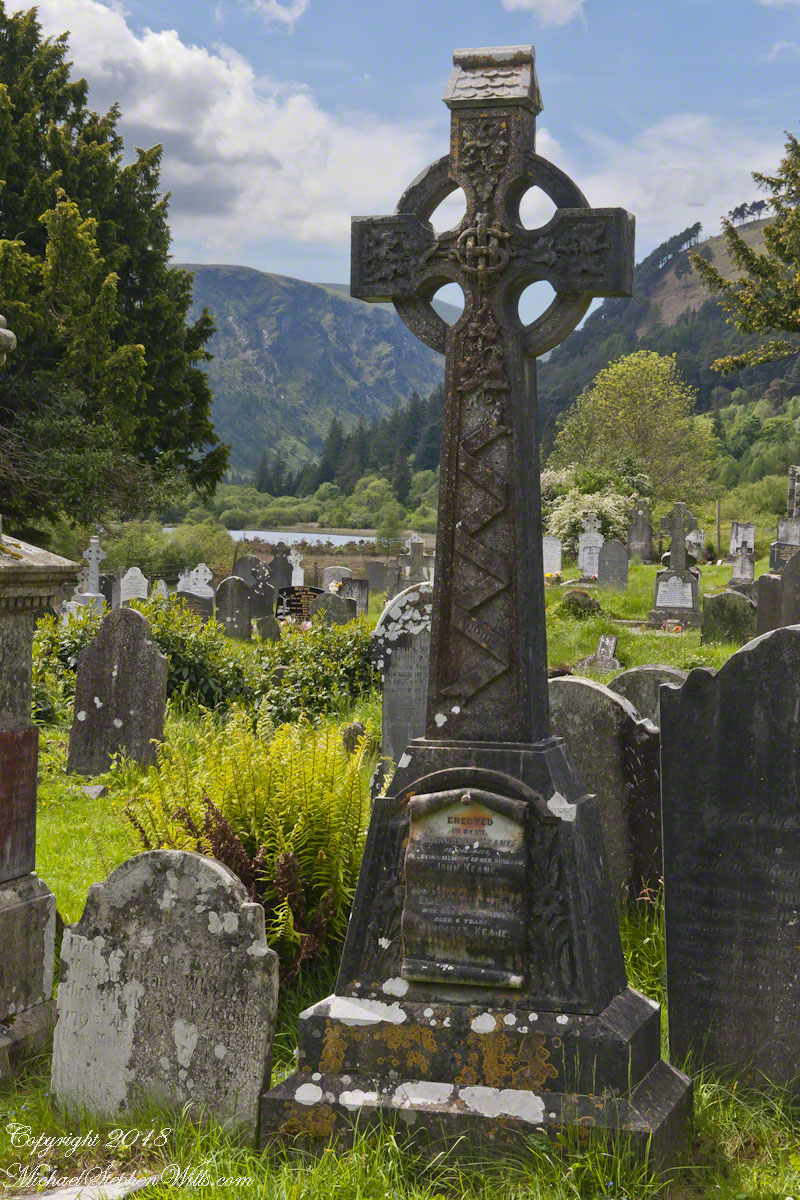

Walking through the monastic settlement, I felt enveloped by a hush both reverential and oddly comforting. The path led me to a cluster of gravestones leaning gently askew, each marked by Celtic crosses standing guard over the memory of those buried below. One cross, carved from sturdy stone, immediately drew my attention with its intricate knotwork etched deep into the surface. The front of it bore swirling designs reminiscent of interwoven vines—symbols of eternity, continuity, and faith. I found myself imagining centuries of pilgrims, each pausing here, hands gently resting on the weathered carvings, offering up their prayers and hopes.

A bit farther on, I came upon a small grouping of headstones bowed in silent unity. Ferns and moss carpeted the ground in bright greens, creating a natural tapestry that wove together life and memory. The slightly overgrown grass softened the entire landscape, allowing each stone to stand quietly yet firmly in the earth. From behind these markers, I caught my first glimpse of the shimmering lake, framed perfectly by the slopes of the valley. The water’s surface reflected the sky’s azure brilliance and accentuated the gentle hush that fell upon the graveyard like a comforting quilt.

As I paused to take a few photographs, I felt a hint of magic floating through the air—an indefinable sense that beyond what my eyes perceived, an age-old spirit thrived. The Celtic symbols on the headstones seemed alive, their swirling knots hinting at the cycle of life and death, the oneness of the world, and the bridging of earthly existence with the mystic realm. I found myself recalling old Irish legends: stories of saints who could converse with animals, of spirits dwelling in hidden glades, of holy wells that healed weary travelers. It felt as though those tales were all around me, wrapped in the tapestry of this timeless valley.

Looking out toward the remains of the stone church—its walls crumbled yet proud—my imagination conjured the chanting of monks, their voices echoing off the surrounding hills. The same forest that sheltered me now would have encircled them all those centuries ago, shifting from season to season. It was easy to picture them gathering by the lake’s edge, cups of cold, clear water cupped in their hands, or moving reverently among the graves of those who had come before them. Here, time seemed an illusion. The line between past and present faded as I stood among these enduring stones.

Winding paths of grass guided me to another section of the cemetery, where weathered inscriptions told the stories of families, lineages, and deep connections to the land. Some headstones were so old that the lettering had nearly eroded, but others still proudly bore legible names and dates. Names like Power, Byrne, and Keane were etched in memory, followed by poignant words of affection and devotion. The place felt both solemn and comforting at once—a harmonious interplay of remembrance, reverence, and the gentle pulse of nature.

A sudden breeze rippled through the trees, setting the leaves to dance and carrying the lilt of birdsong across the valley. I turned to admire the view once more, and there, between towering yew trees, the lake glowed like a polished mirror. Soft clouds glided overhead in a pale blue sky. The entire scene seemed woven from a single, unbroken strand—mountain, forest, gravestone, lake, and sky merging in a spellbinding harmony. It was the kind of moment that invited awe, a moment in which to lose oneself and yet feel more fully found.

I left the cemetery with a deeper sense of peace than I had known in some time. The photographs I took may capture the beauty of Glendalough’s ancient crosses and serene landscape, but it’s the intangible hush of centuries and the gentle brush of magic that remain with me. With every step back toward the car, I felt the warmth of timelessness, and as the day’s golden light enveloped the stone monuments behind me, I carried away a tiny spark of the valley’s enchantment—a reminder that some places are truly touched by the divine.Look closely at the carved scroll at the foot of the cross.

For more background of this site, see my posting “The Cloigheach of Glendalough.”